- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This is a handbook full of practical ideas to use with anyone who is experiencing mild to severe memory difficulties. The suggestions and activities can be used when working with individuals or groups. The strategies can, in fact, be used by anyone young or old, who has become worried about loss of memory. The handbook provides: information about how memory works and different types of memory; an outline of what can affect memory; strategies to aid memory; activities to practice using the strategies; and activities to keep the brain active and maintain memory. The resource is aimed at staff in care environments such as residential homes, day centres, social clubs, support groups, carers or anyone who might be concerned about loss of memory. It promotes understanding about memory difficulties and provides a wide range of strategies and activities to aid response to individual need. Approximately 200pp; A4 wire-o-bound.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Memory Handbook by Robin Dynes in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Inclusive Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part 1

About memory

In order to support people who may be experiencing memory loss, it is important to ha ve some basic understanding of how memory works and what can prevent it from functioning well.

How Does Memory Work?

Memory is just one function of the brain which in turn governs the body and enables us to think, be creative, plan, feel emotions, take action, learn skills, build knowledge and understanding and carry out everyday tasks. All these functions are interconnected.

Frequently, memory is compared with a database, a library or a filing cabinet. These analogies are inaccurate. Science now suggests that memories are not stored in a single place but in a network of neuron (nerve-cell) pathways. Every memory begins when we receive input from our senses – what we see, hear and experience. This input is transmitted like an electronic signal from one nerve-cell to another, forging a unique pathway among the billions of neurons in the brain.

It is more helpful to think of memory as a three-stage process, rather than as a database or filing cabinet of information. This process of memory is the key to its working well. Also, the better all the constituent parts of the brain function, the better our memory will serve us.

The three-stage process

Stage 1: Selection

We are overwhelmed by an avalanche of sensory input every day. This is what we see, hear, smell, taste, touch and experience. Look around the room or out of the window or make a cup of tea and your brain is noticing everything. Where does all this information go? Most of it vanishes very quickly. You may have noticed someone walking past the garden gate while you were making a cup of tea. You saw the person; your brain registered the information. But, because someone passing the garden gate is a common occurrence and you attach no significance to it, you dismiss it as insignificant and the visual image of it melts away.

The only way to hold on to these fleeting memories is to pay particular attention to the sensory input, give it significance and take it to the next memory stage.

Stage 2: Storage

Temporary storage

This is the stage when you pay particular attention to something. If you knew that later in the day the police were going to ask you about the person who passed the garden gate, you would register that person's hair colour, what they were wearing, their probable age, and so on. You might even write this down to make sure you did not forget. This stage is known as short-term or working memory; it can last from a few seconds to a few hours. Think of the last time someone gave you a phone number, you got distracted looking for a pen to write it down and had to ask for it to be repeated. Storage at this stage is short. For example, most of us can hold only about seven digits or items at a time in short-term memory.

This temporary storage is very important. It enables us to note down appointments, make everyday decisions and hold conversations. We need to remember only what the person we are talking to said a few seconds ago to be able to respond to it. It can then be safely forgotten.

All the information we absorb – from sounds, smells, touch, pain, pleasure, films we watch, people we meet, emotions we experience, places we visit – is processed through our working memory. Once there, it is sorted, compared and connected with information already stored in long-term memory. During this processing the brain decides whether the new information needs to be retained or discarded. If it is to be retained, we work on it by rehearsal, repetition, and so on, in order to transfer it into long-term memory.

Thinking about information and what it means and organising it by using strategies requires a lot of effort, but doing this ensures that the memory remains. If we remembered everything we experienced, our memories would very quickly become cluttered with an overload of irrelevant material, making it difficult to remember specific things.

During this working memory process, people sometimes forget things they would rather not, such as where they put their glasses or gloves, or they lose their train of thought in a conversation. When this occurs people often say things like ‘My memory is going’ or ‘I’m getting very forgetful’. Often, these problems can be credited to short-term or working memory lapses.

Long-term storage

To retain information for days, months or years, it needs to be consolidated into long-term memory. There is an unlimited amount of capacity to do this. We store these memories by paying close attention, by practising how to do something or by repetition of the information. This reinforces the nerve-cell pathway tracks, making them stronger. An event might have had particular significance or importance to us; the information or experience might add to our current knowledge about a subject. However, even long-term memories will fade with time if they are not revisited now and again – the pathways will begin to wane. But there is the potential to remember them for ever.

It is believed that the main types of information stored in long-term memory can be classified. Types include:

- Semantic memories. These are the facts, figures and words you have learned. They include the recall of words used to form sentences, rules of grammar, mathematical formulas, historical dates, titles of books, the date you were born or information such as that acorns come from oak trees. They are facts that seem to stand alone and are the same for everyone.

- Episodic memories. These are your personal memories of the events in your life. They are automatically stored without effort. The events may be your first day at school, when you got married, a special holiday, having your first child, getting fired from your first job or being humiliated by someone. They may be pleasant or unpleasant events and have strong emotional associations.

We do tend to forget some details of important events, however. You may remember getting married but forget what Aunt June gave you as a wedding present. We also tend to forget mundane and unimportant events in life. If 25 June 2008 was a routine day in which nothing of importance happened, you are unlikely to remember what you did or where you went without looking back in an old diary to check. Even then you may not remember any of the details. - Procedural memories. These are physical skills we learn, such as how to ride a bike, drive a car, play an instrument, brush our teeth, walk, swim or carry out countless other actions every day. We do them without having to think consciously about the process. Procedural memories are stored throughout the brain, which ensures that they are well retained and less likely to be lost. Individuals often retain these skills even though they may not be able to remember a family member's name.

- Prospective memories. This is the ability to remember what you need to do in the future, such as keep a dental appointment, post a letter, ring your daughter, take tablets or return a book to the library. Everyone experiences failures of some 'prospective memories', or forgets to do some things. Without prospective memory it would be difficult to function and, indeed, even hazardous-forgetting to check that the gas has been turned off, for example, or not checking the traffic before crossing the road.

Stage 3: Recollection

In order to retrieve information from long-term storage we need to reverse the process and bring it back to the surface in our working memory. What we want to recall will have been allocated to one of the different types of memory as instructed by our brain. To recall a specific piece of information we need to retrieve the correct pathway to it. However, there are billions of different paths. How do we find the right one that will ‘spark’ the information we want?

We use cues and associations to help us find our way. If you cannot remember the name of someone you worked with five years ago, the first thing that might come to mind is the name of the company you worked for, then what department she was in, what she did, how she dressed, how outspoken she was in meetings and, finally, how uncomfortable you felt when she challenged you for making a 'sarcastic' remark. At this point you remember the name, Sue Barton. Your brain will have completed this round-about route in a second without you even being aware of this pathway-finding process happening.

Both the company and the woman's name will have been retrieved from 'semantic'-type memories, because they are historical facts. And the event Sue challenged you about, being a personal experience, will be lodged as an 'episodic'-type memory. So, you can see that it is a very complex system and the working memory may have to dart between different memory types to provide cues and associations to enable recovery of the information you want.

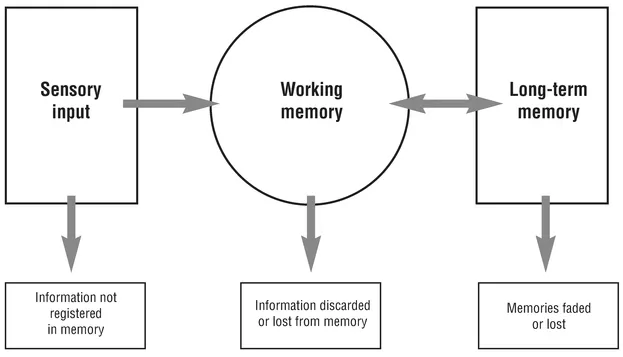

Figure 1:1 shows a simple diagram which illustrates the three-stage process.

Figure 1:1The three-stage process

The process makes it easily apparent that:

- Strategies are needed to help with registering information, ensuring that strong pathways are laid down and that strong cues and associations can be used to 'spark' the recovery of memories from long-term storage.

- We need to maintain a healthy and active brain in order to ensure that all the systems function well. Hence the common saying, 'Use it, or lose it.'

- Memory is not static. New information may alter your perception of something, changing how you think about an event and your memory of it.

- Not registering all information and forgetting information that is no longer used, useful or essential is necessary to avoid clogging up the system.

What can go wrong?

As much as we might like to think that all our recollections are accurate, we all experience memory lapses and malfunctions from time to time. Table 1 lists some of the things that can affect memory.

Table 1 What can affect memory

| What can happen | How the memory process is affected |

| Important information is ignored or unimportant facts are selected | The person is unable to recall something they now think is important |

| There is an overwhelming amount of information to be absorbed | Overload makes it difficult to register detail, to evaluate and sort it out in a way that makes sense, and to store the material |

| The mind is distracted by something else | The person feels stressed, anxious, excited, agitated, preoccupied with a problem, overwhelmed by distracting noise or for some other reason is unable to focus on what is happening or being said. The distraction interferes with the process of registering and processing important information |

| Memory is influenced by perception | We all remember events differently because we perceive them differently. Also, our sensory memory influences our version of reality. If you are attending a dinner and talk and you have a cold, and you also have little interest in the subject, you might recall the meal as tasteless and the talk and discussions with others as boring. On the other hand, your partner, who is interested in the subject, might remember the meal as excellent and the talk and discussions as invaluable |

| Physical or mental health problems interfere | The drain of continuous physical pain, distressing mental health problems and side effects from medications can interfere with the mind registering and processing information |

| Senses become impaired | Imperfect sight, hearing and use of the other senses will influence how information is registered and processed. Someone who does not hear and understand properly what is being said will miss chunks of information, make assumptions – often incorrectly – and lose interest or register incorrect details in their memory |

| Memories are altered to accommodate new information | Important or useful information is discarded or lost because the mind has decided, in the light of new facts, that the former data was incorrect or is no longer essential |

| Significant changes in personal circumstances | Dealing with a combination of changes, such as bereavement, other losses (eg friends or independence), or change of accommodation and in financial circumstances, can affect memory. Many older people are forced to cope with a number of these distracting and anxiety-raising types of change within a short period of time. Also, memories need to be revisited from time to time to keep them fresh. Opportunity to do this with younger family members may become limited |

| Blank spots create inaccurate recall | During the process of calling up detail from various locations in the brain, there may be some blank gaps. The brain may fill these in by making assumptions and jumping to conclusions which are inaccurate |

Ageing and Memory Loss

As people age they often begin to worry about loss of memory.People of all ages have memory lapses, miss appointments, fo...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Thanks and Acknowledgements

- Contents

- Introduction

- Who the book is for

- What the book contains

- How to use the book

- Making the activities relevant to daily lives

- Part 1: About memory

- Part 2: Daily living strategies

- Part 3: Exercises and activities for practising strategies and to aid memor

- References

- Appendix