Chapter 1

Overview of Modernising Medical Careers and the Foundation Programme

Introduction

Once upon a time, there was a girl called Hannah. Now Hannah was a bright girl and liked helping people, so she decided that she wanted to be a doctor. She went to medical school, worked very hard for five years and at the end became Dr Hannah. Dr Hannah liked medical school a lot, especially all the blood and gore, so she decided she wanted to be a trauma surgeon. She completed her pre-registration house officer (PRHO) year, worked as a senior house officer (SHO) for three years and as a registrar for four years, then got a job as a consultant in a prestigious London teaching hospital, married a semi-literate footballer and lived happily ever after.

Although people have always perceived this to be the way progression in medical careers happens, it is in fact a myth. Climbing the job ladder in medicine has always been a messy affair, and certainly not something for the faint-hearted. For one thing, it never happened as easily as in Hannah’s case. In theory you only worked as an SHO for three or four years, but the reality was that this was the minimum. You applied for jobs that often had 1,000 other candidates going for them, so you can imagine jobs didn’t often go to the plucky young SHO applying for the first time. As a result, it is not uncommon to hear stories of people who have done five, six or even seven years as an SHO. And if you think you’re sorted once you become a registrar and have picked up your National Training Number then think again, because the whole scenario repeats itself -complete your training and then apply for jobs over and over and over again until you finally get lucky.

All in all, it was a long, hard graft, and so it was decided that postgraduate training needed to change. And what a change it was! Modernising Medical Careers, commonly abbreviated to MMC, is probably the biggest change in medicine since the NHS started. It is big, and when we say big, we mean BIG. We’re talking New Coke replacing Classic Coca-Cola big; we’re talking Peter Crouch standing on Jan Roller’s shoulders big; we’re talking double-quarter-pounder with cheese, mayo, salad, bacon, fried egg and a hash brown all in a sesame bun, with a side order of large fries, onion rings, a double deluxe coke and an apple pie to finish. That’s how big it is. Remember when The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air replaced the actress who played Vivian? It’s even bigger than that. This is a fundamental change to how everything is done in medicine, and it’s going to affect everyone currently in medical school.

Modernising Medical Careers

MMC came about as a result of a 2002 consultation paper called Unfinished Business, written by the Chief Medical Officer, Sir Liam Donaldson. Now Sir Liam wasn’t too happy with the way postgraduate medical training in the UK was working. In particular, he was worried about senior house officers. SHOs make up half of all training doctors in the UK, but have long had to make do with the short end of the stick. To begin with, even the statement ‘SHOs are half of all training doctors’ is in fact a misnomer, because almost half of these posts were dead-end jobs/short-term appointments that were not part of any training programme. And across the whole board, there was a lack of careers advice to make sure you were on the right track to do what you wanted to do. The problems with the SHO grade didn’t end there. A big issue was that the quality of the jobs varied wildly. Some firms could be amazing, teaching you everything you needed to know to be the world’s best SHO. Others weren’t so good and you could find yourself having to make do with little or no teaching in subjects that were of no use to you, and with no methods of assessing whether or not you knew all that you should. There was very little option for flexibility in your training and, as we’ve already mentioned, there was no guarantee how many years you’d have to work before you were accepted into specialist training.

So Sir Liam proposed some changes to the grade. First of all, he wanted to get rid of the issue of different programmes being of different quality, so he suggested that rules be set on how training would be delivered. This would accompany a programme curriculum that would set out what an SHO needed to know. All of this would culminate in what had previously been a novel concept – quality assurance of training. Doctors would be tested on this knowledge by assessments that were consistent wherever you worked and whatever specialty you were working in. The training would be broadly based, so no matter what SHO job you did, it would equip you with the skills necessary to move into your desired specialty. There would be a time-cap to it all, so no more waiting around for seven years before you progressed to specialist training. (The latter point sounds great, but it goes hand in hand with another principle of reform that what the NHS needs in terms of specialists, and what doctors want to be, are not necessarily the same thing, but more on this later.) Finally, the changing demographics of medicine were taken into consideration, and with the majority of medical students carrying two copies of the X chromosome, Unfinished Business proposed that there should be more opportunities for flexible training to ensure that things like wanting a family wouldn’t disadvantage trainees.

So, armed with all of these recommendations made by the Nation’s Doctor™, the powers that be got together and designed MMC. Now if you’ve been following so far, you’ll probably agree that the basic premise of MMC sounds reasonable enough – postgraduate training is a long, hard slog, demoralising to those in it and not producing enough doctors in the right specialties for the public. The solution to this? A complete overhaul of postgraduate medical training.

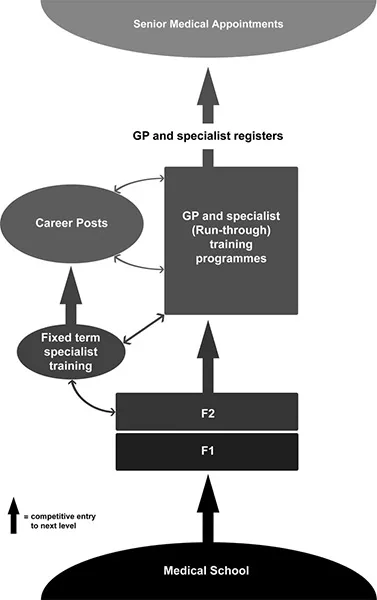

Figure 1.1

The new structure to postgraduate training

As mentioned earlier, the lack of a clear pathway of progression was one of the main problems with the old training grade. The answer to this problem was to devise a streamlined scheme whereby doctors move from one stage to the next in a continuous flow without hanging about. A medical career will now start with a two-year Foundation Programme. This is subdivided into foundation year 1 (FY1) and foundation year 2 (FY2), and both will last for precisely one year – no more, no less. FY1 will still be a pre-registration year, and successful completion of it will be needed before the General Medical Council (GMC) add you to their list of registered medical practitioners. FY1 posts are only open to those who have not previously worked as a doctor anywhere in the world, but FY2 posts are open to all. On completion of FY2, doctors will immediately move into specialist training. This is one of the big changes – it’s no longer a case of ‘you’re now eligible, so start applying for posts’, as was the case with the old SHO grade. It’s now ‘you’ve finished your foundation training, so bugger off!’ You will have to move into specialist training, and although in theory this sounds like a good idea, it also causes one of the biggest problems of MMC. You see, in the old system, a lot of the waiting was self-inflicted – doctors waited around for years because they were hoping to be a plastic surgeon and there were only a few training jobs out there in that field. That’s undoubtedly a pain, but at least you got to do the job that really interested you once you finally entered specialist training. No such luck in the MMC world. Once you finish your specialist training you will be faced with two options.

Apply for specialist training posts, and if you don’t get the one of your choice make do with whatever specialties are left at the end of it all.

Decide that you only want to work in one field and if you don’t get a place on a training scheme, follow that specialty in a non-training grade, the so-called ‘career grades’.

A word about career grades. This new and enticing moniker should be approached with caution. Non-training grades were formerly known as career-grade doctors or trust doctors, and these posts were regarded as career suicide. Once you took such a post, you could kiss your hopes of ever becoming a consultant or principal GP goodbye, because you’d be stuck there for the rest of your working life. They are posts created by trusts to fill specific shortages in their departments, and are not approved by postgraduate training deaneries, which means that you will never acquire the skills you need to move up the ladder. Even though MMC does say there will be a route of escape for those in career grades, it’s still best to avoid these positions at all costs. That means you’re best sticking to the specialist training path and taking whatever it throws at you, even if it’s not exactly what you want. While one of the biggest attractions of a medical career has always been the diverse choice of jobs and the ability to specialise in the one that really grabs you, the thinking behind this change is logical enough. Specialties such as microbiology, psychiatry, histopathology and public health medicine are obviously crucial to the health service, but are not attracting enough applicants to their training schemes. Rather than providing the opportunity for everyone to train in the field of their choice and the UK ending up with thousands of plastic surgeons (and a much prettier population as a result, so it’s not all bad!), the specialties available in specialist training will mirror the requirements of the population, so if there’s an acute shortage of radiologists, the scheme will aim to churn out more of them.

There’s another problem here, too. You’re deciding your future career path after only two years in medicine, or more accurately a year and a half, because you’ll be applying for specialist training posts halfway through FY2. This requires extreme focus on the part of the medical student/junior doctor. Next time you’re on the ward, ask one of the registrars or consultants when they decided on their chosen specialty. The chances are they’ll tell you that it was deep into their SHO training, probably after dabbling with two, three or maybe even four other career paths beforehand. Ask them whether they had any idea what they’d do when they were in medical school, or if they thought they’d be doing this back then. They will laugh at you. The reality is, in the post-MMC world, you’re going to have to start thinking seriously about careers that interest you while you’re still in medical school. Whether this is a good thing or a bad thing remains to be seen.

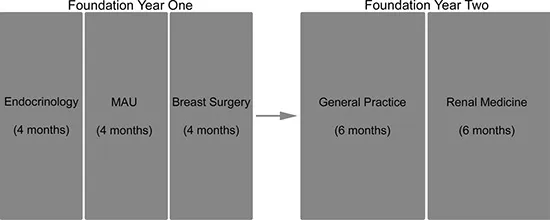

The make-up of the foundation years

The key word here is ‘generic’. Whatever job you do, in whatever specialties, in whatever hospital in the UK, the theory is that you’ll be learning the same things, as guided by the curriculum (more on this in Chapter 4). In each foundation year you’ll do a mix of specialties in posts which can be 3, 4 or 6 months in length (but always a cumulative total of 12 months, so you could do three 4-month jobs, or two 6-month jobs, for example), and soon 90% of all Foundation Programmes will include general practice as one of the rotations. This is in line with the government’s wishes for more doctors to become general practitioners because they see them as gatekeepers to the NHS, who can treat patients before their illness becomes serious and not refer them to expensive hospital beds.

In addition to this likely GP rotation, each programme will have a good mix of specialties, including at least one surgical post and as much exposure to emergency medicine as possible. The issue of specialties suffering from a shortage of doctors is addressed here, too. The aim is that as few people are forced to move into specialties that they don’t like as possible, and rather that they will consider jobs that previously hadn’t crossed their minds. This will be achieved by including the specialties that are perceived as ‘less desirable’ as part of many of the Foundation Programmes, and it looks as if it’ll be a good idea. Certainly this was the case when the pilot programmes experimented with including a general practice rotation. A number of the trainees had no interest in it before they started the rotation, but changed their minds after they had tried it. Even those who had their minds set on other careers still said that they gained a lot from the experience and didn’t regret it in the least. The theory is that this will work for other specialties, too. For example, many people are put off genitourinary medicine by inaccurate preconceptions, but those who have worked in it find it a pretty satisfying career. Even if it doesn’t catch your interest, it provides a good foundation of knowledge that is useful in other fields such as gynaecology and rheumatology. The posts that you do in the foundation years will have no impact whatsoever on the careers that you can apply to in specialist training, so it’s to your advantage to experiment here and try specialties you’d not previously considered or that you know little about. Equally, the hospitals that you work in won’t matter, so all those myths about how good it looks on your CV if you do your first job in a busy teaching hospital go straight out of the window. You might have your heart set on being a paediatric surgeon, but you never know – those three months in a district general hospital doing chemical pathology may come in very useful in the future!

Figure 1.2

Students will either apply to a full two-year Foundation Programme and so will know the make-up of both years in advance, or will initially apply only for FY1, and halfway through that will apply for FY2.

Specialist training

Once you’ve done your two foundation years, you move on to specialist training or ‘run-through training’ as it’s now called. As with the foundation years, this will be for a fixed term, the length differing for each specialty. Each field of medicine will adhere to its own set curriculum to make sure that you learn everything you’re meant to know. On completion you’ll be awarded a CCT – a Certificate of Completion of Training. Get this baby and you’ll be free to apply for consultant and principal GP jobs to ...