- 378 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Electronics for Radiation Detection

About this book

There is a growing need to understand and combat potential radiation damage problems in semiconductor devices and circuits. Assessing the billion-dollar market for detection equipment in the context of medical imaging using ionizing radiation, Electronics for Radiation Detection presents valuable information that will help integrated circuit (IC) designers and other electronics professionals take full advantage of the tremendous developments and opportunities associated with this burgeoning field.

Assembling contributions from industrial and academic experts, this book—

- Addresses the state of the art in the design of semiconductor detectors, integrated circuits, and other electronics used in radiation detection

- Analyzes the main effects of radiation in semiconductor devices and circuits, paying special attention to degradation observed in MOS devices and circuits when they are irradiated

- Explains how circuits are built to deal with radiation, focusing on practical information about how they are being used, rather than mathematical details

Radiation detection is critical in space applications, nuclear physics, semiconductor processing, and medical imaging, as well as security, drug development, and modern silicon processing techniques. The authors discuss new opportunities in these fields and address emerging detector technologies, circuit design techniques, new materials, and innovative system approaches.

Aimed at postgraduate researchers and practicing engineers, this book is a must for those serious about improving their understanding of electronics used in radiation detection. The information presented here can help you make optimal use of electronic detection equipment and stimulate further interest in its development, use, and benefits.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 The Future of Medical Imaging Understanding Our True Limitations

1.1 INTRODUCTION

1.2 WHERE ARE WE GOING?

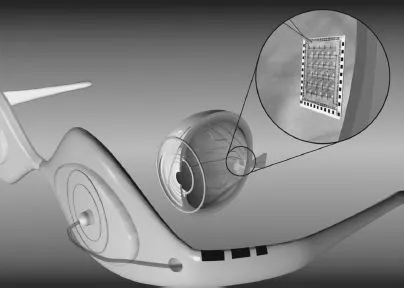

1.2.1 THE EYECAM

1.3 MAKING HEALTH CARE MORE PERSONAL

1.3.1 ADVANCES IN DIGITAL AND MEDICAL IMAGING

Migration to digital files: Photographic plates were once used to “catch” X-ray images. These plates gave way to film, which in turn is now giving way to digital radiography. Through the use of advanced digital signal processing, X-ray signals now can be converted to digital images at the point of acquisition while imposing no loss in image clarity. Digital files have a variety of benefits, including eliminating the time and cost of processing film, as well as being a more reliable storage medium that can be transferred near-instantaneously across the world.Real-time processing: The ability to render digital images in real time expands our ability to monitor the body. Using digital X-ray machines during surgical procedures, doctors can view a precise image at the exact time of surgery. Real-time processing also increases what can be done noninvasively. For example, the Israeli company CNOGA* uses video cameras to noninvasively measure vital signs such as blood pressure, pulse rate, blood oxygen level, and carbon dioxide level simply by focusing on the person’s skin. Future applications of this technology may lead to identifying biomarkers for diseases such as cancer and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).Evolution from slow and fuzzy to fast and highly detailed: Today’s magnetic resonance imagers (MRIs) can provide higher quality images in a fraction of the time it took state-of-the-art machines just a few years ago. These digital MRIs are also highly flexible, with the ability to image, for example, the spine while it is in a natural, weight-bearing, standing position. With diffusion MRIs, researchers can use a procedure known as tractography to create brain maps that aid in studying the relationships between disparate brain regions. Functional MRIs, for their part, can rapidly scan the brain to measure signal changes due to changing neural activity. These highly detailed images provide deeper insights into how the brain works—insights that will be used to improve treatment and guide future imaging equipment.Moving from diagnostic to therapeutic: High-intensity focused ultrasound (HIFU) is part of a trend in health care toward reducing the impact of procedures in terms of incision size, recovery time, hospital stays, and infection risk. But unlike many other parts of this trend, such as robot-assisted surgery, HIFU goes a step further to enable procedures currently done invasively to be done noninvasively. Transrectal ultrasound,† for example, destroys prostate cancer cells without damaging healthy, surrounding tissue. HIFU can also be used to cauterize bleeding, making HIFU immensely valuable at disaster sites, accident scenes, and on the battlefield. Focused ultrasound even has a potential role in a wide variety of cosmetic procedures, from melting fat to promoting formation of secondary collagen to eradicate pimples.The portability of ultrasound: Ultrasound equipment continues to become more compact. Cart-b...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- About the Editor

- Contributors

- Chapter 1 The Future of Medical Imaging: Understanding Our True Limitations

- Chapter 2 Detector Front-End Systems in X-Ray CT: From Current-Mode Readout to Photon Counting

- Chapter 3 Photon-Counting Energy-Dispersive Detector Arrays for X-Ray Imaging

- Chapter 4 Planar and PET Systems for Drug Development

- Chapter 5 PET Front-End Electronics

- Chapter 6 Design Considerations for Positron Emission Tomography (PET) Scanners Dedicated to Small-Animal Imaging

- Chapter 7 Geiger-Mode Avalanche Photodiodes for PET/MRI

- Chapter 8 Current-Mode Front-End Electronics for Silicon Photomultipliers

- Chapter 9 Integrated Charge-Measuring Systems for Radiation Detectors in CMOS Technologies

- Chapter 10 Current- and Charge-Sensitive Signal Conditioning for Position Determination

- Chapter 11 Analog-to-Digital Converters for Radiation Detection Electronics

- Chapter 12 Low-Power Integrated Front-End for Timing Applications with Semiconductor Radiation Detectors

- Chapter 13 Time-to-Digital Converter Circuits in Radiation Detection Systems

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app