- 423 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

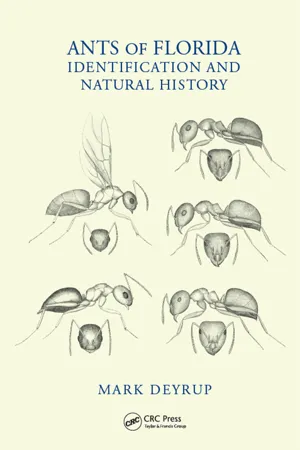

Ants are familiar to every naturalist, ecologist, entomologist, and pest control operator. The identification of the 233 species of Florida ants is technically difficult, and information on Florida ants is dispersed among hundreds of technical journal articles. This book uses detailed and beautiful scientific drawings for convenient identification. To most Florida biologists ants are currently the most inaccessible group of conspicuous and intrusive insects. This book solves the twin problems of ant identification and the extraordinary fragmentation of natural history information about Florida ants.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART ONE

An Overview of the Ants of Florida

INTRODUCTION

The following sections are an informal compendium of all the patterns that I see in the ant fauna of Florida. This includes not only patterns in distribution but also ecological patterns, the kinds of relationships between ants and humans, and even the trends in the nomenclature and research dealing with Florida ants. For an introduction to ant morphology see Plates 1 and 2.

FLORIDA ANT STATISTICS

There are 239 species of ants known in Florida. The ants of the state are relatively well known, and the users of this book should expect to find accounts of almost any ant they find. Two lines of evidence, however, suggest that there are some more species to be discovered: (1) Additional species have been accumulating, although at a slow rate, right up to the time of writing these words (2015); (2) several species have been collected in Florida only once or twice, a circumstance that always hints that there are more species to be found. Species that are very localized or difficult to collect (imagine a species that lives in hollow twigs at the tops of trees in Hell’s Half Acre in Jefferson County) are likely to have been overlooked. The real number of species of ants in Florida is probably close to 245 or 250, excluding any new exotic species that may invade in the future. Any enthusiastic and ingenious ant hunter is likely to be rewarded eventually with species that have never been reported in Florida. Some of these ants will be species unknown to science. The best area to find unreported native species is the northern tier of counties in the Peninsula and all of the Panhandle, a poorly studied area with localized and endemic species of animals in many groups, from frogs to beetles. Newly introduced species could turn up almost anywhere but are most likely to be found near major ports.

With its 239 species, Florida is one of the most ant-rich states, a fact strangely absent from the promotional literature of the Florida Tourist Bureau. One site in Florida, the Archbold Biological Station in Highlands County, has 128 species of ants, the most ants known for any site in the United States. Florida undoubtedly has more species of ants than any other eastern state, largely because its unique fauna of tropical and subtropical species is combined with the more widespread fauna of the southern Atlantic Coastal Plain, with elements of the southern Appalachians thrown in. The only other eastern state that has been carefully surveyed is North Carolina (Carter 1962; Guénard et al. 2012), which has 192 species, a remarkably high diversity that is attributable to North Carolina’s great diversity in topography and habitats.

As one goes north from the Carolinas, the ant fauna inevitably diminishes because ants are basically creatures of warm climates, even though there are some groups of ants, such as the genera Formica, Lasius, and Myrmica, whose rich (and confusing) proliferation of species is almost entirely restricted to temperate regions.

Large southwestern states have even more ant species than Florida. California has 270 species (Ward 2005), New Mexico has 239 species (Mackay and Mackay 2002), and Arizona probably has even more species than New Mexico (Hunt and Snelling 1975). West Texas, with an area approximately twice that of Florida, has 184 species listed (Cokendolpher 1990), and we already know of many additional species from the pine woods of East Texas and from the Brownsville area. It may still be difficult, however, to find a southwestern site with more than the 128 species known from a relatively small Florida site, so Florida may be able, in some sense, to retain its proud claim to being the “antiest” state for some time to come.

NAMES OF FLORIDA ANTS

On the Joys and Frustrations of Knowing the Names of Ants

Many naturalists will use this book primarily for identifying ants. Biologists know that the purpose of the scientific name of an organism is to provide a unique pair of code words under which is indexed the information about that organism. Every correct identification is a key to a file box of knowledge, whether in somebody’s head (“What do you know about Temnothorax torrei?”), or (formerly) in the indices of an abstracting journal, now replaced by electronic search engines, or the book you are holding in your hand. The knowledge-holding boxes, of course, are often empty. The enterprising Florida naturalist who encounters a small yellow ant, identifies it as T. torrei, and looks it up in the index of this book for the species account, still would not be able to find out how this species makes its living, because nobody knows. That too, however, is useful information. In the naturalist’s head, a new, empty file box has been set up, ready to receive any observations on T. torrei.

Field biologists are aware of another phenomenon: the possession of a name sharpens the senses. The mechanism in our brain that sifts sensory input is connected to our information files, and shunts into a spotlight of greater awareness the organisms that we recognize. To know more is to see more. This discussion is all by way of explaining what might seem an inordinate preoccupation with names in this book, and among many biologists, who are willing to argue for hours over the application of a name. This obsession has an adaptive basis, although, like other adaptive obsessions, it can easily get out of hand.

Changing Names

The nomenclature of Florida ants is not quite settled. There are taxonomic problems about certain species in approximately 10 of the 49 genera of Florida ants. This may be frustrating, but it is no great cause for concern, as biologists have not been given any deadline for finalizing the names of ants, or any other organisms. The great majority of names used here should remain stable. A residue of species may have their names changed for two reasons.

Generic names may be changed when the higher classification of a group of ants is revised. The Florida species of Conomyrma, for example, were returned to the genus Dorymyrmex in Shattuck’s 1992 revision of the Dolichoderinae. All such changes are made for the sake of the internal consistency in our classification of a group. There is no such thing as a biological genus concept, in the sense that there is a biological species concept. The use of the name Conomyrma elegans is not really wrong, because there could be no doubt which species was intended, and because a revision does not have the force of law, but most myrmecologists would agree that Dorymyrmex elegans is the current usage. Some names, Colobopsis, for example, are applied as a subgenus of Camponotus by some and as a full genus by others. This seems like a small difference in opinion that can eventually be resolved with a revision of the species groups of Camponotus, but the alleged misuse of a genus name can occasionally arouse as much pedantic petulance as the misidentification of a species.

Species names (or “specific epithets”) can change when our concept of a species changes. The Florida subspecies of Leptogenys elongata, Leptogenys elongata manni, was raised to species level some years ago, so we now recognize two species, L. elongata and L. manni (Trager and Johnson 1988). Names can change on lists because the name was mistakenly applied. Old records of Monomorium minimum from Florida probably all refer to two other species, Monomorium viridum and Monomorium trageri (DuBois 1986). Species names can change for the trivial reason that there was an earlier, disused name that takes priority, but most species name changes reflect advances in our understanding of the status of the particular species.

There will be some species-level name changes in Florida ants. We are, for example, waiting for names for several species of Brachymyrmex. Crematogaster ashmeadi might be a complex of at least two species. Working out correct species names has a biological significance, because species, when looked at in a particular area and era, have an ecological and genetic integrity that is absent at the genus level and above.

This manual generally follows the subfamily classification outlined in Table 1 of Ward (2007) and the lists of genera from Barry Bolton’s A New General Catalogue of the Ants of the World (1995, with online updates) and Synopsis and Classification of Formicidae (2003) with a few recent updates of particular genera.

On English Names for Florida Ants

Most species of insects do not have English names or “common names” of any sort. There is a good reason for this. There are hundreds of thousands of species of insects, and most of these species can only be identified by a few experts. Many naturalists are interested in ants, but the number who can identify most of the species they see is very small. The specialists who can identify species of the genus Crematogaster, to take a typically difficult genus of ants, are quite satisfied to have only the single Latinized name for each species. They certainly do not want to deal with a batch of vernacular names, when they already know species by their formal scientific names, such as Crematogaster atkinsoni and Crematogaster cerasi. In practice, almost all our discussions of such species are with each other, as nobody else seems very interested. The term common name seems absurd in such a context: fewer people would know the species by its common name than by its scientific name. To make matters worse, if one gives a species a common name, for example, calling Odontomachus ruginodis the “West Indian Snapping Ant,” this name might be unacceptable in Spanish-speaking countries such as the Dominican Republic and Cuba, where this ant also occurs, so they might want their own name.

I personally have had a reverence for the system of binomial nomenclature since the age of 9 or 10, when I began to teach myself scientific names, which I thought of as the “real names” of animals and plants. I remember my surprise when I discovered that scientific names are occasionally changed. I am still quite conservative about nomenclature, and find myself resentful of the attitude among some modern systematists that names of genera are bits of falsifiable trivia that can be changed whenever a vagrant intellectual breeze rustles the topmost twigs of some computer-generated phylogenetic tree. Fortunately, ants have not suffered much in this regard, and most of the recent changes, such as transferring the Florida species Iridomyrmex pruinosus to the genus Forelius (Shattuck 1992), are broadly based in ecology, morphology, and phylogeny.

Although I was teaching myself scientific names of insects with flash cards while standing in line at the school cafeteria at the age of 15, I would not hold others to this standard of oddness. The world is largely populated with people who are less peculiar, even as teenagers. Scientific names are not at all the currency of ordinary conversation. They are likely to be seen as meaningless concatenations of syllables, difficult to remember, embarrassing to try to pronounce. I spend some of my time talking to gardeners and other informally trained naturalists, and have become painfully familiar with the looks, ranging from befuddled to hostile, that I get when I start to toss around scientific names. If I say “Caribbean Trailing Ant,” I get an entirely different reaction than if I say “Monomorium ebeninum,” even though the two names are equally unfamiliar. Sometimes, I think that there might be some brainstem response to a person who seems to interlard their conversation with foreign words from an alien tribe. Sometimes, I think it is simple resentment that I am providing an unintelligible name that will be impossible to remember. It does not matter; it is undesirable to have anything, including a mass of insect names intoned in Latin, standing between the naturalist and nature.

I have therefore concluded that all the ants of Florida should have English as well as scientific names. I am encouraged by the fact that better entomologists than I have made the same decision. In 1953, Jaques Helfer provided English names for the many orthopteroids in his manual of the group. In Charles Covell’s field guide to eastern moths (1984), a book that finally made moths easily accessible to a generation of naturalists, each moth has a common name. He claims that most of these names were taken from a preexisting list of common names (in Sutherland 1978), but the great majority of them cannot be found in that list, and are really from Holland’s pioneering 1903 moth guide, or Covell invented them himself, with admirable aptness and brevity. Among guides to Florida insects, the books on dragonflies (Dunkle 1989), damselflies (Dunkle 1990), and grasshoppers (Capinera et al. 2001) include English names for all species. There are only a few available English names for Florida ants, so I have coined almost all the common names in this book. The Entomological Society of America has allocated to itself the authority to establish “approved” common names (Sutherland 1978), but this list is restricted to the species “commonly of concern to entomologists,” which excludes almost all the ants of Florida. I doubt that I am the best person to make up names; many of the names in this book are more appropriate than concise—“the Wooly Pygmy Snapping Ant” is even clumsier than “Strumigenys lanuginosa.” Perhaps these names will become streamlined with usage.

Subspecies Names for Florida Ants

Subspecific names have a dismal history in myrmecology. Specimens of ants that looked different might be given different subspecies names, even though the differences were related to caste, or to differences in the preservation of specimens. To make matters much worse, many ants were saddled with varietal names, so a specimen might have four or even five names attached to it. As Creighton (1950) pointed out, there was no simple way out of this “altogether horrendous maze of nomenclature.” Some of these names applied to ants that should really be considered distinct species, some applied to ants that were legitimate distinctive geographic subspecies, and a large number of them applied to variants that had no geographic basis and were different castes, or specimens that were discolored in preservation, or, as Creighton discovered in a surprising number of cases, distinguished by characters that seemed to be completely imaginary. Many Florida ants were caught up in this mess, but, largely thanks to Creighton, we have relatively few such problems remaining. Fossilized vestiges of these problems, like taxonomic coprolites, can still be seen occasionally. The Florida species Odontomachus ruginodis, for example, was described by W. M. Wheeler in 1905 as Odontomachus haematodis insularis ruginodis. The last name, referring to a “variety,” has no taxonomic standing, so ruginodis was not really the name of anything until 1935, when M. Smith used it as a subspecific name, Odontomachus haematodis ruginodis. This is why M. Smith, not Wheeler, is considered the author of O. ruginodis in the species account in this book. Odontomachus ruginodis was first recognized as a full species by E. O. Wilson in 1965. This little tangle and a few thousand similar cases are succinctly dissected in Barry Bolton’s 1995 catalogue, a book that is a miracle of scholarship.

The flagrant abuse of the subspecies concept in ant taxonomy may have helped inspire Wilson and Brown’s general attack on the practice of designating subspecies (1953). To this day, American myrmecologists often avoid using the surviving subspecific names, and almost nobody names new subspecies of ants. But although the logic of the 1953 attack on subspecies is as cogent as ever, and continues to appeal to each new generation of young taxonomists, the usefulness of the geographic subspecies category persistently overwhelms all theoretical objections, and seems set to outlive all its detractors. The young want definitions that always work, but eventually we must always come back to working definitions. Although I am not about to name new subspecies of Florida ants, I recognize the legitimacy of geographic subspecies, and deal with them as they come up in the species accounts.

One More Thing about Names: Author Names

Attached to the name of each ant is the name of the person who described it, or rarely, as in the case of O. ruginodis, the first person who used the name properly. When a species is transferred to a genus that is different from the genus in which it was first described, the author’s name goes in parentheses. The species Conomyrma elegans Trager, when transferred to Dorymyrmex, became D. elegans (Trager). I generally follow Bolton’s 1995 catalogue for author names. The use of an author name outside of a taxonomic treatise is, as the myrmecologist Bill Brown used to say, “An exercise in useless pedantry.” In this book, author names appear only in one place, at the beginning of each species account.

ECOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF FLORIDA ANTS

Ants as Predators

Most species of ants are predatory, as well as scavengers, and ready to attack any inadequately defended arthropod. Adult ants are not, strictly speaking, carnivorous, since they feed mostly on fluids, either sweet fluids such as nectar, or the juices of prey. The predaceous behavior of ants is inspired by the appetites of larvae back in the nest, and the more food that can be found, the faster the nest grows. With this growth comes strength for nest defense and an ability to invest in the expensive business of producing queens and males that will disperse to new sites. Among more generalist predatory ants, there may be some targeting of the most available type of prey. This allows individual ants to become more efficient at finding and dealing with prey. This also makes these ants more important as regulators of ecosystems because they concentrate on species that are especially abundant.

Anti-Ant Defenses

Few terrestrial or arboreal arthropods would be able to survive in Flor...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- About the Author

- 1 • AN OVERVIEW OF THE ANTS OF FLORIDA

- 2 • SPECIES ACCOUNTS

- Literature Cited

- Plates

- Distribution Maps

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Ants of Florida by Mark Deyrup in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Biology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.