![]()

PART I

Political contexts, affect, art, and ethical relations in research

![]()

1

REFUSING TO CHECK THE BOX

Participatory inqueery at the radical rim

Michelle Fine, María Elena Torre, David Frost, Allison Cabana and Shéár Avory

My father enrolled me in conversion therapy, from the ages of 5–10; I was a Black and Indigenous child sitting with a therapist every week who tried to convince me I am not who I am.

My advocacy is dedicated to young transgender, nonbinary and queer youth from pre-school to young adulthood. To you I want to say:

I see you.

I hear you.

I believe in you – in us.

We are the change we have been waiting for.

(Shéár Avory, national social justice advocate for the advancement of social, economic, racial and gender justice and the empowerment of young people)

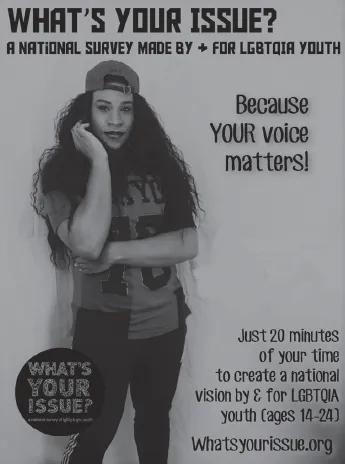

What’s Your Issue? (WYI) is a national participatory survey designed by and for LGBTQ+ & GNC (Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Queer, plus and Gender NonConforming) youth, primarily youth of color, particularly those most marginalized by public ideologies and institutions, alienating school cultures, inadequate housing options, aggressive policing and deeply ambivalent families. Designed in the spirit of Shéár Avory’s call to see, hear and believe, WYI was constructed by a research collective of youth and adults, most queer and of color, activists and academics, synchronized with a series of ten local sketches, crafted from experiences of growing up gay/lesbian/trans/queer/gender nonconforming in Jackson, Mississippi; Tucson; Los Angeles; Boston; Detroit; Saint Louis; New Orleans; Seattle; Jersey City; and New York City. With a multi-method design, we sought to gather material that could stretch wide across the United States (6,000+ surveys from every state in the nation) and would be enriched by deeply place-based policy struggles that affect the everyday lives of queer youth differently in distinct parts of the nation. From the massive database, we are producing videos, an online archive of lives, statistical policy documents, resources for state-specific legal campaigns, a card game called “Radical Wit” based on the qualitative responses, and critical methodology pieces like this one. We write this chapter as a multi-generational collective of researchers/analysts/activists, exploring how we work together, in highly contentious times, when race/gender/sexuality identity categories are at the core of human rights advocacy and are being contested ferociously by young people refusing to “check the box.”

In this essay we explore a range of methodological dilemmas, written as a diary of unfolding epistemological, methodological, representational and political muddles we literally stepped into as we developed, implemented and analyzed, over two years, a national, inter-generational, participatory survey by and for LGBTQ+ & GNC youth. The methodological challenges we explore might best be forecasted as a series of nagging questions addressed to all who are conducting research with, or alongside, communities under siege:

- Representations and “damage”: How can researchers represent the serious wounds of betrayal and structural violence without reproducing narratives of damage and despair?

- Refusing boxes and documenting disparities: How is it possible, in these revolting times, to blow open restrictive identity categories (e.g. race, gender and sexuality) and still reveal the systemic claw marks of structural, social and intimate violence delivered along the categorical fault lines of race, gender and sexuality?

- Armwrestling neoliberalism: In a profoundly neoliberal/victim-blaming moment, how can researchers dissect neoliberal particles floating in narratives of injustice, and still sustain arguments that forcefully link structural violence to complex lives and communities?

- Creating research “of use”: How can researchers collaborating with activist and/or practitioner communities produce various kinds of products that speak boldly to/with communities under siege, speak strategically to policy makers, enhance the work of practitioners and expand social theory about the consequences of systemic injustice?

- In whose voice?: In a mixed-methods, inter-generational and participatory design, breathed into existence through a National Research Collective, who is “we” and in what dialect do we speak our collective evidence?

And so, below we try to offer good enough, never totally satisfying, responses in times when researchers have an obligation to stand with movements for justice, with provocative baskets of evidence that challenge dominant narratives, structures and policies and incite the social imaginary about social transformation.

What’s your issue?

What’s Your Issue? (WYI) was/is hugely ambitious, politically and methodologically, in our desire to link a large-scale quantitative and qualitative survey, across 50 states, Puerto Rico and Guam, to reveal the landscape of intersectional struggles and forms of resistance engaged in by LGBTQ+ & GNC youth and young adults aged 14–24. This critical participatory research project is a perfect “window” into the dilemmas of researching identities, oppression and resistance, through an intersectional lens (Alcoff, 2005; Crenshaw, 1989; Nash, 2008; Nadal, 2017). This essay takes up the particular methodological challenge of how to study and represent the “complex personhoods” (Gordon, 1997) of LGBTQ+ & GNC youth and young adults: how to ask, interpret and re-present gender, sexuality and racial/ethnic identities that refuse/resist/contest boxes in “revolting” times.

At lunch with the philanthropists who funded WYI, María and Michelle were asked:

Have you ever noticed that the leaders of major youth organizing movements – Dreamers, Prison Abolition, Black Lives Matter, Fight for $15, Muslim justice work, Environmental Racism, Educational Justice, UndocuQueer … are disproportionately queer and trans youth of color?

(Youth organizing funder, New York City, 2014)

In 2014, María Elena Torre and Michelle Fine were asked to meet with three philanthropists – all lesbian and each of different racial and ethnic backgrounds who knew our work on critical participatory action research in women’s prisons and with highly marginalized youth. While their philanthropic portfolios focused on the needs of LGBTQ+ & GNC youth of color, they were concerned that the small pool of existing national research on the experiences of LGBTQ youth (a) focused importantly but primarily on depression, bullying, suicide and HIV; (b) rarely included BTQ+ or GNC youth; (c) drew from largely White and “out” samples; (d) failed to include young people exiled to the social margins; and (e) was not designed by or from the perspective of young people. As important, they were concerned that LGBTQ+ youth’s rich knowledge and understandings of the complex structural intersections of sexuality, gender, immigration, housing, mass incarceration, family violence, street violence, inadequate health care, aggressive policing and serious miseducation were not represented in the research. While these funders supported activist groups, organizations and sheltering spaces (e.g., UndocuQueer, Foster by Gay, BreakOUT! and Detroit Represent!), the experiences of these young people had not been included in the empirical tales traditionally circulated by mainstream LGBTQ advocates for equal rights. They worried that the effects of respectability politics and desires for assimilation were, in the words of Shéár Avory, “cis-tematically” excluding these stories from the narratives of human rights “Equality” campaigns, shoving LGBTQ+ & GNC young people into yet another closet.

The funders knew that gender nonconforming, trans and queer youth were disproportionately homeless, in foster care and involved with juvenile justice; that many young people find the binaries of gay/lesbian and heterosexual, as well as male and female, to be psychically violent “straight” jackets. They knew that the very identity politics that had ushered victories in the courts and at the ballot box also erased the “inconvenient truths” about gender and sexual fluidity; flexibility; and contingency of young sexual bodies. With very important exceptions of scholars who did this work (e.g., Diamond, 2009; Kosciw et al., 2012; Nadal, 2013, 2017), the field needed more intersectional research on the landscape of structural violence against LGBTQ+ & GNC youth of color. Thus, these funders sought a national participatory project from the perspective of LGBTQ+ & GNC youth that could gather narratives and responses from a much wider berth of queer, trans and gender nonconforming young people living at the margins, specifically those young people of color who might tell a different story about the desires, betrayals, dreams, demands and radical imaginaries. And with that, WYI was born.

WYI: participatory design commitments

We formed a national advisory board of LGBTQ+ & GNC activists, artists, educators, policy makers and researchers, and then a research collective of university researchers, advocates and youth organizers from ten cities. Together we sketched and evolved principles of participatory design and analysis:

- Recruit and oversample youth who have been under-represented in traditional surveys, by intentionally recruiting (in person, through organizations and social media) trans/nonbinary youth, rural youth, young people involved with multiple “systems” (e.g. foster care, juvenile justice, shelters), out of school youth, youth of color and LGBTQ/GNC youth who were 14–24. We were moved and inspired by a beautiful patch of writing by Junot Díaz on mirrors and monsters, and sought to create a research project that would open a hall of mirrors:

You know how vampires have no reflections in the mirror? If you want to make a human being a monster, deny them, at the cultural level, any reflection of themselves. [G]rowing up, I felt like a monster in some ways. I didn’t see myself reflected at all. I was like, “Yo, is something wrong with me?” That the whole society seems to think that people like me don’t exist? And part of what inspired me was this deep desire, that before I died, I would make a couple of mirrors. That I would make some mirrors, so that kids like me might see themselves reflected back and might not feel so monstrous for it.

(Junot Díaz in Steeler, 2009, NJ.com)

With social media, we recruited widely, seeking to create “mirrors” even in our WYI flyers and gathering a diverse national sample. Our recruitment materials included images of our co-researchers, in this case D’Mitry from Boston GLAS (Figure 1.1).

The WYI sample includes 5,860 LGBTQ+ & GNC respondents, aged 14–24, and over-represents trans, nonbinary and gender nonconforming youth as well as youth of color; those who have been “multiply” marginalized in “systems” including social service agencies, shelter and juvenile justice. The survey asked questions generated largely by young people about dreams, desires, identities, activisms, supports, yearnings and futures, as well as challenges and pain. Representing respondents from every state in the country, Puerto Rico and Guam, 57% of the sample identifies as trans/non-binary/gender nonconforming; 39% as youth of color; 23% as religious; 39% report having difficulty due to a disability; 81% are currently in schools, 60% of those in high school; 46% are under the age of 18; and our youth researchers want you to know that 43% are in a relationship with “someone special.” Being loved and lovable is a demographic category of deep existential meaning to our research collective.

- Design a research platform that welcomes participants to express their full and complex selves, and encourages participants to contribute their full selves to the expanding archive of queer youth narratives.

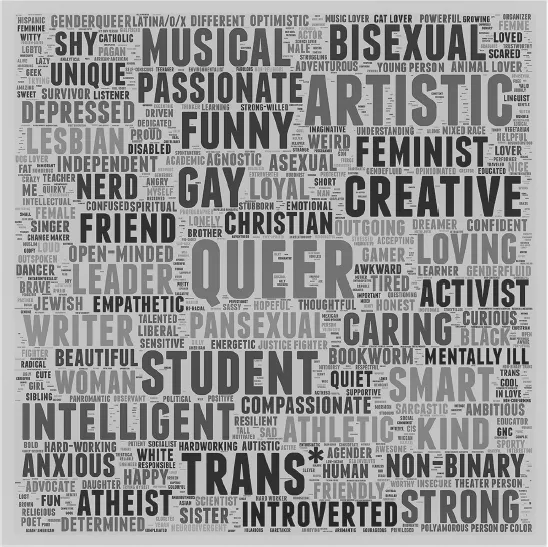

We did not want the survey to “smell” like an epidemiological or psychiatric instrument, a “test” or a survey constricted by judgments about “normalcy.” We wanted instead to design a survey instrument that would creatively invite young people to feel recognized, to be motivated to contribute their stories to an archive of vibrant selves, passions, pains and commitments. To signal our desire for expansive selves, we opened the survey (taken largely online) with a simple question: Describe yourself in 5 words. And we got a mosaic of descriptors, with size reflecting the frequency of each response (Figure 1.3).

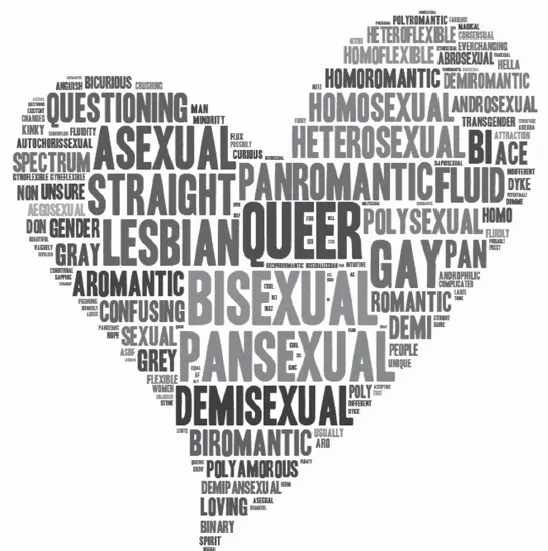

Early in the survey, we asked participants to describe in their own words their gender, sexuality and race/ethnicity. They presented more than 30 gender categories and a wide array of sexuality orientations (Figure 1.2).

A bit further into the survey, young people were asked to tell us about their “happiest or proudest moment” and they poured sweet and sour stories into our growing archive of LGBTQ+ & GNC narratives:

Not really a specific moment, but time in my life: graduating from college. I was proud that I graduated with a double major and magna cum laude and that made me happy. But as I walked down the aisle with my diplomas and had someone point and laugh at my heels, I just thought about all the times I considered killing myself/driving off the road or all the times I (un)intentionally put my life in danger by mixing 3–4 drugs, drinking myself to death, doing anything I could to get a high no matter how sketchy. My diplomas felt more like a badge of honor saying: I survived a place that was not meant for me and I know how much that survival is bound up in those before me and those that don’t have the privileges I had going to college and having money … so it’s a weird sense of pride/happiness, complicated and incomplete, one that comes with an obligation and impulse to do something with my position but given that it’s only been a few months since I passed that moment in my life, I still feel proud of myself for it, because it wasn’t fucking easy.

(Queer, a Transbian, GNC, Trans femme trying to figure it out, In process, White)

My proudest moment: Holding a paid internship at a Wall Street investment bank, Deutsche Bank, while I was homeless. I was a homeless teenage Wall Street intern. Wall Street by day, LGBTQ youth shelter by night.

(Bisexual, GNC, Black)

I was 18 years old, living in shelter in Brooklyn when I got the call that changed my life. I had gotten an apartment through a housing program. It was a small studio, but I didn’t care. I was just happy that I got myself out of the shelter where there were fights all the time. Now I am not homeless anymore, but a few other people that I used to hang out with are still homeless today and that’s 6 years later from when we were all homeless.

(Lesbian, Agender, Stud, Just Me, Black, Afro-Indigenous Haitian)

When I was 21 I came out to my parents and while it was definitely not my happiest moment, looking back now I would have to say it’s my proudest. I had to work hard and overcome a lot of things internally to be who I am today. We were in a hotel room for my sister’s volleyball tournament and I handed them a manila folder with a letter I had been writing for the past six months. Coming out to first generation immigrant Christian parents is not an easy feat. I broke their hearts when I told them who I was and while we are still in the process of figuring out how to love and understand each other, I’m glad I can die unapologetic about who I am or what I stand for.

(Lesbian, Cis Female, Chinese American)

Thousands of narratives are now being archived, braiding rich, complex stories of pain and accomplishment; oppression and defiance; alienation and relentless demands for recognition.

- Document intersectional structural violence and radical enactments of resistance. With quantitative and qualitative prompts, standardized and “home-grown/youth-developed” measures, closed ended and open ended, we also gathered evidence of policy-induced structural precarity (economic, housing, policing, schooling and hunger struggles) disaggregated by race, gender, sexuality and sometimes region of the ...