- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Kinship and Continuity is a vivid ethnographic account of the development of the Pakistani presence in Oxford, from after World War II to the present day. Alison Shaw addresses the dynamics of migration, patterns of residence and kinship, ideas about health and illness, and notions of political and religious authority, and discusses the transformations and continuities of the lives of British Pakistanis against the backdrop of rural Pakistan and local socio-economic changes. This is a fully updated, revised edition of the book first published in 1988.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Kinship and Continuity by Alison Shaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Anthropology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 FROM PAKISTAN TO BRITAIN

The primary motive for Pakistani migration to Britain in the late 50s and early 1960s was socio-economic. Single or bachelor-status married men leaving wives and children in Pakistan came to Britain to earn and save money that would enable their immediate kin at home to settle debts, extend landholdings, build new houses, give larger dowries, start businesses and so on1. The economic ‘pull’ towards Britain was a powerful one, because wages for labouring jobs in Britain in the early 1960s were over thirty times those offered for similar jobs in Pakistan. In Mirpur, for instance, the average weekly wage was equivalent to approximately 37 pence; in Birmingham, a Pakistani’s average weekly wage was £132.

Given this pecuniary motive, it is at first puzzling that most Pakistani migrants to Britain were from only a few particular areas in Pakistan. These areas are parts of the Panjab, the North West Frontier and Mirpur (see Map 1.1). Why did migrants not come to Britain from other parts of Pakistan, such as Baluchistan, which are in many respects poorer than the main regions of out-migration? Explanations usually mention the ‘push’ of pressure upon land, the high population density and the fragmentation of landholdings in these areas. This, however, is not the whole story for there are parts of India where population pressure on land is higher, but people have not emigrated in significant numbers. It is also clear that traditions of migration and local population movements have also helped shape migration from particular areas3 and the regions represented by Pakistanis in Britain are no exception.

Britain’s Pakistani Population

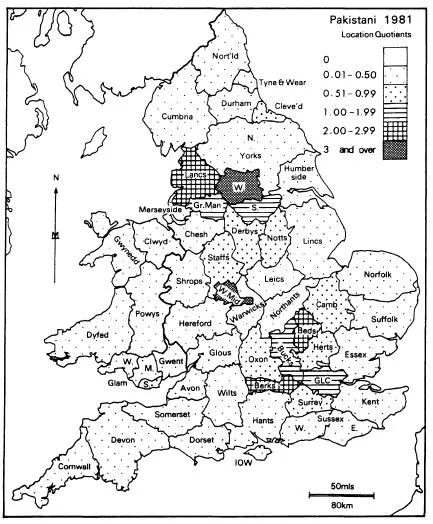

According to the 1991 U.K. Census, which included for the first time an explicit ethnic question, there are 476,555 Pakistanis in Britain who constitute 0.87% of Britain’s population of nearly 55 million. The Census data identify Pakistanis as the third largest ethnic group in Britain4. In England, the largest Pakistani settlements are in West Yorkshire and the West Midlands (see Map 1.2). Bradford, for instance, has a Pakistani population of some 49,0005. Birmingham, Leeds, Sheffield, Preston and, in Scotland, Glasgow also have a substantial Pakistani presence and there are smaller settlements further south in Aylesbury, Bristol, High Wycombe, Luton, Oxford, Reading, Slough and parts of London.

Map 1.1 Map of Pakistan

This settlement pattern to a large extent reflects the industrial labour shortages of the 1950s onwards in cities where industry was expanding. Britain exploited her historical links with India, Pakistan and the Caribbean by directly and indirectly recruiting labour from these countries and after 1962 by issuing work vouchers. The process brought workers to the Midlands manufacturing industries and to the West Yorkshire steel and the Lancashire textile industries. Subsequently, too, there were labour shortages in the south. It is not surprising, then, that Britain’s Pakistani population is unevenly distributed, but what is less evident is that different areas of origin in Pakistan are also unevenly represented in different parts of Britain, as the somewhat piecemeal evidence from various local studies suggests (data on region of origin rarely enter public records).

Map 1.2 Distribution of Pakistanis in England and Wales (Map reproduced from Vaughan Robinson, Transients, Settlers, and Refugges: Asians in Britain, Oxford Clarendon Press, 1986, p. 38, by permission of Oxford Univeristy Press.

Region of origin, like birādarī, or caste, is an important aspect of identity: Pakistanis distinguish themselves as ‘Mirpuris’ (from Mirpur), ‘Jhelumis’ (from Jhelum), and so on. Strangers usually first ‘place’ each other by asking about their region of origin in Pakistan, and then more specifically about their town or village; this process also provides one measure of social distance. Allegiances of kinship and village, which often influence participation in social activities, also in effect delineate broadly regional groups in the context of community politics and the mosques.

Evidence from the two largest British Pakistani settlements, those of Bradford and Birmingham, shows four main regions of origin:

1. Mirpur district in Azad Kashmir (disputed territory, here treated as part of Pakistan);

2. Attock (formerly Campbellpur) district, locally called the Chhachh (sic) area;

3. some villages in Nowshera sub-district, Peshawar; and

4. some villages in Rawalpindi, Jhelum, Gujrat (not to be confused with Gujarat state in India) and Faisalabad (formerly Lyallpur) districts6.

These categories provide a general guide to the regional composition of Britain’s Pakistani population as a whole, with Mirpur district probably accounting for the majority of British Pakistanis, but the relative proportions of different groups vary from one Pakistani settlement to another and each settlement has a distinctive regional character. My impression is that Mirpuris predominate in Birmingham, Bradford, Newcastle, High Wycombe and Bristol. People from Attock and Nowshera have a significant presence in Bradford and Birmingham. In Rochdale and Bristol, the main regional division is between Mirpuris from Azad Kashmir and Panjabis7. Mirpuris are not always the largest groups; in Rochdale, there are apparently more Panjabis than Mirpuris8. The relative strength of different Panjabi groups, such as Faisalabadis and Jhelumis, also varies from one settlement to another. Faisalabadis are a significant presence in Newcastle, Huddersfield, Rochdale, Glasgow and Dewsbury9. Jhelumis apparently form a substantial proportion of the Pakistani population of the London borough of Waltham Forest.

Oxford’s Pakistani Population

How do Oxford Pakistanis fit into this picture? 1991 Census data for Oxford city give a Pakistani population estimate of 2,026, of which less than half were born outside the U.K. This may be an underestimate: my own estimate in the early 1980s was 1,930, of which the majority lived in east Oxford (Table 1.1). Many families have moved house within east Oxford since then, some have moved outwards further east and to other suburbs of the city, while a few ‘new’ Pakistani families have moved into east Oxford from other parts of the country. East Oxford remains the practical and symbolic focus of settlement; it is here that most of the Pakistani businesses are based, and where, on a prime site, the foundation stone for a purpose-built mosque was laid in 1997.

Oxford Pakistanis are of quite diverse regional origins. The general consensus, supported by my 1984 household survey (Table 1.1), is that Jhelumis are the largest group, while Faisalabadis, Mirpuris and people from Attock are also well represented, in roughly equal proportions. Each of these groups has certain distinctive characteristics such as their Panjabi dialect.

Many of the Faisalabadis were originally refugees from Jullundhur district (now in Indian Panjab) during the Partition of India and Pakistan in 1947, and their spoken Panjabi is closer to that of the Sikhs. People from Attock district bordering the North West Frontier province sometimes identify themselves as Pathans, like those from Nowshera in the North West Frontier Province, but their mother-tongue is a Panjabi dialect. ‘True’ Pathans are considered to be Pashtoo speakers of tribal (Afghan) origins. In a dispute which took place concerning the mosque, for example, a Panjabi group comprising people from many different districts of the Panjab was opposed by a so-called ‘Pathan party’ which included both Panjabis from Attock district and ‘real’ Pathans. Some Panjabis from Attock district have adopted the title ‘Pathan’ in Oxford, for it conveys a certain distinction and is associated with a respectable caste status, though their birādarī-based kinship organization is more characteristic of Pakistani Panjabis than of ‘true’ Afghan tribal origins.

| APPROXIMATE SIZE AND DISTRIBUTION OF OXFORD’S PAKISTANI MUSLIM POPULATION, 1979–80 | ||

| City of Oxford Polling District | No. of Pakistani Muslim households | No of persons |

| EAST OXFORD | 207 | 1,387 |

| (including St. Clements) WEST | 28 | 188 |

| SOUTH | 27 | 181 |

| REMAINING DISTRICTS | 26 | 175 |

| TOTAL | 288 | 1,931 |

Note: This estimate was based on the city of Oxford electoral register for 1979–80. I counted households whose occupants have Muslim names, excluding those I considered to be Bangladeshis, Iranians, visiting Muslim academics and so on, and adding 13 east Oxford households personally known to me whose occupants’ names were not on the electoral register. I made a population estimate by multiplying my estimated number of Pakistani Muslim households by an ‘average household size’ (of 6.7) that I calculated from a sample of 50 east Oxford households a s follows: | |

| No. in household | 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 |

| No. of households | 1 6 4 14 9 7 5 3 1 |

These figures included the householder’s children and other resident adults except visiting grandparents and non-Pakistanis. The resulting ‘average household size’ is not, of course, an average completed family size. | |

| Table 1.1 | |

Mirpuris comprise the fourth largest group in east Oxford, whereas elsewhere in Britain Mirpuris often predominate, sometimes, as in Oxford, forming separate settlements10. In Oxford, the Osney settlement at the western end of the city was distinctly Mirpuri, at least until the closure in 1982 of the Mother’s Pride Bakery where a substantial proportion of the Mirpuri workforce had been employed since the 1960s. Since then, Osney’s Mirpuri settlement has declined; some families have moved to other cities, some to east Oxford and some have returned to Pakistan.

In the past ten years, there has been some residential mobility around and into Oxford, but there is little evidence that t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Maps

- Tables

- Figures

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- A Note on Transliteration

- Introduction

- 1. From Pakistan to Britain

- 2. The Process of Settlement

- 3. Households and Family Relationships

- 4. The Idiom of Caste

- 5. Birādarī Solidarity and Cousin Marriage

- 6. Honour and Shame: Gender and Generation

- 7. Health, Illness and the Reproduction of the Birādarī

- 8. Taking and Giving: Domestic Rituals and Female Networks

- 9. Public Faces: Leadership, Religion and Political Mobilization

- 10. Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Glossary

- Index