- 452 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Clinical Neurovirology

About this book

This is a comprehensive reference that includes the basic science, clinical features, imaging, pathology and treatment of specific viral entities affecting the central nervous system (CNS). It will assist professionals in their attempt to identify, examine and manage viral CNS infections and unravel the therapeutic and diagnostic challenges associated with viral CNS disorders.

Key Features

- Features MRI scans, histopathology and lined diagrams showing pathophysiology

- Much has happened in our understanding of CNS infections in recent years and a comprehensive book that covers the entire subject is much needed.

- There is ongoing interest in infectious disease. The increasing globalization of medicine is putting demands on many more people to become familiar with issues from around that world that they did not see in training.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

PART I

Introduction: Epidemiology, socioeconomic impact, and challenges ahead

1 Introduction to virus structure, classification, replication, and hosts

Philippe Simon and Kevin M. Coombs

2 Neuropathogenesis of viral infections

Avindra Nath and Joseph R. Berger

3 An approach to pathogen discovery for viral infections of the nervous system

Prashanth S. Ramachandran and Michael R. Wilson

4 Neuropathology of CNS viral infections and the role of brain biopsy in the diagnosis

Susan Morgello

1

Introduction to virus structure, classification, replication, and hosts

PHILIPPE SIMON AND KEVIN M. COOMBS

1.1 Virus structure

1.1.1 General nature of viruses

1.1.2 Virus morphology

1.1.2.1 Virion size and complexity

1.1.2.2 Viral nucleic acid

1.1.2.3 Viral proteins

1.1.2.4 Host proteins

1.1.3 Capsid morphology

1.1.4 Other virion components

1.2 Virus classification

1.2.1 Classification schemes

1.2.1.1 The formal classification scheme

1.2.1.2 The epidemiological and etiological classification schemes

1.2.1.3 Classification based upon morphology and composition

1.2.1.4 The Baltimore classification scheme

1.2.2 Integration of classification schemes

1.2.2.1 DNA viruses

1.2.2.2 RNA viruses

1.2.2.3 Unclassified agents

1.3 Viral replication

1.3.1 The viral growth curve

1.3.2 Steps in viral replication

1.3.2.1 Overview

1.3.2.2 The early events

1.3.2.3 The middle events

1.3.2.4 Late events

1.3.2.5 Lysogeny

1.4 Hosts

1.4.1 Cell tropism

1.4.2 Tissue tropism

Acknowledgments

References

1.1 VIRUS STRUCTURE

1.1.1 General nature of viruses

Although the concept of an infectious “virus” is only about 100 years old, diseases caused by these agents have been known since ancient times. For example, both rabies and polio, which are discussed in greater detail in later chapters of this volume, appear to have been known in Egypt around 2000 BC, almost 1000 years before the time of the Pharaoh Tutankhamen. Significant work preceding and during the nineteenth century ce allowed visualization of bacteria and established their disease-causing properties. It became appreciated toward the end of the nineteenth century that some agents capable of causing illness were small enough to pass through filters known to block bacteria. Thus, the term virus (Latin for poison) was coined to describe these “filterable toxins.” However, it was soon realized that viruses were different from poisons. Toxins can be diluted when serially passaged from one host to another, whereas viruses undergo multiplication. Although humans have been aware of viruses for a relatively short period of time, these agents are probably as old as life itself and have probably coevolved with other forms of life.

Viruses are among the simplest and smallest of currently known living organisms. In fact, because of their simplicity, there is some debate as to whether viruses should be considered living. Most viruses consist of both protein and nucleic acid. Viroids (plant pathogens that consist solely of RNA) and prions (agents that appear to consist solely of protein) are exceptions. Viruses generally exist in two forms. The actively replicating virus inside an infected cell is the form that may be considered “alive.” The extracellular form of the virus is known as the virion. The virion is analogous to a seed or spore. It generally is a stable “crystalline” structure whose primary function is to protect the genetic material until the nucleic acid reaches the interior of a suitable host cell. No virus is capable of growing by itself. All must make use of macromolecular “building blocks” (amino acids, nucleotides, and, in some cases, lipids) and employ enzymes found within living cells. Thus, all viruses are obligate intracellular parasites.

1.1.2 Virus morphology

1.1.2.1 VIRION SIZE AND COMPLEXITY

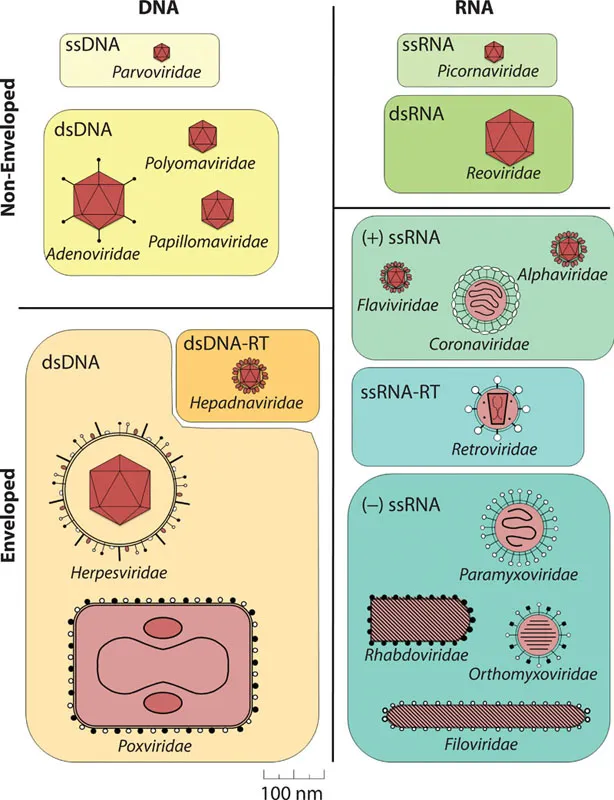

There is enormous variability in the size of virions. The smallest animal virions are the parvoviruses (e.g., the human parvovirus B19), which belong to the family Parvoviridae. As detailed later in Section 1.5, almost all viruses are organized into families, which are designated with an italicized name ending with the suffix-viridae. Groups of viruses (families) may be referred to by their italicized family name (e.g., Parvoviridae) or may be referred to by a nonitalicized generic name (e.g., parvoviruses). Both conventions are used in this chapter. Parvovirus virions are less than 20 nm in diameter (Figure 1.1). The largest animal viruses (e.g., vaccinia virus and the smallpox agent Variola major) are members of the Poxviridae family. Poxvirus virions are generally approximately 200 × 300 nm in size (Figure 1.1) and are barely visible by light microscopy. Ebolaviruses, the causative agents of lethal Ebola hemorrhagic fever, and members of the Filoviridae family are filamentous virions with diameters of only 80 nm but lengths of up to 14,000 nm [1]. As another example, several viruses colloquially known as giant viruses can infect amoebas. These include Mimiviruses, Pandoraviruses, Megaviruses, and Pithoviruses whose virions can reach up to 1.5 μm [2]. There also is significant variability in virion complexity. Parvoviruses consist of a small piece of nucleic acid surrounded by 60 copies of a single protein. Other viruses, such as the Polyomaviridae and the Papillomaviridae, may be more complex and larger, composed of a larger piece of nucleic acid and more than 60 copies of a single protein. Most virions are even more complicated and larger. Some (e.g., adenoviruses) contain a single piece of nucleic acid surrounded by multiple different proteins that are not present in the same quantities; some (e.g., rubella virus and various equine encephalitis viruses, which belong to the family Togaviridae) contain the same number of various proteins but also contain a lipid membrane (envelope); some (e.g., rabies virus, which belongs to the family Rhabdoviridae; measles virus and mumps virus, which belong to the Paramyxoviridae; herpes simplex viruses and cytomegalovirus, members of the Herpesviridae; and the human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], which belongs to the family Retroviridae) contain different numbers of various proteins as well as a membrane; some (e.g., members of the family Reoviridae) contain different numbers of various proteins as well as multiple segments of nucleic acid (all of which must be present for the virion to be infectious); and some (e.g., the influenza viruses, members of the Orthomyxoviridae) contain different amounts of various proteins, multiple segments of nucleic acid and an envelope. Finally, some fungi and plant viruses such as the Faba bean necrotic stunt virus of the Nanoviridae family have a segmented genome encapsidated in individual capsids. These multipartite viruses require all the sub-particles to infect a cell in order to provide all components for replication [3].

1.1.2.2 VIRAL NUCLEIC ACID

With the possible exception of the prion agents, all currently known viruses contain either DNA or RNA as their genetic material. Most viruses use their genetic material both for replication and for transcription. Replication is the process whereby the viral genetic material is copied into exact replicas that will be packaged into progeny virions (discussed more fully in Section 1.6). Transcription involves the generation of messenger RNA (mRNA), whether from RNA or DNA, for the eventual production of viral proteins. Thus, one convenient way to group viruses, for ease of classification and discussion, that bears directly upon how (and where) the virus replicates and causes pathology is by nucleic acid type (Figure 1.1). For example, most DNA viruses require enzymes for DNA replication and synthesis. These enzymes, if provided by the host cell, are located within the host’s nucleus, so most DNA viruses replicate inside the host nucleus. One group of viruses that are exceptions to this generalization are the Poxviridae, large complex viruses that encode all their necessary DNA enzymes and thus can replicate in the cell’s cytoplasm. Conversely, RNA viruses do not generally require DNA enzymes (although retroviruses are an exception), so RNA viruses generally replicate in the cell’s cytoplasm. In addition to the retroviruses, which use a DNA intermediate, some RNA viruses, such as the influenza viruses, carry out some of their replicative steps in the cell’s nucleus because they need to “steal” components from cells before those cellular elements leave the nucleus.

The viral ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Editors

- Contributors

- PART I INTRODUCTION: EPIDEMIOLOGY, SOCIOECONOMIC IMPACT, AND CHALLENGES AHEAD

- PART II DNA VIRUSES

- PART III RETROVIRUSES

- PART IV RNA VIRUSES

- PART V MISCELLANEOUS

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Clinical Neurovirology by Avindra Nath, Joseph R. Berger, Avindra Nath,Joseph R. Berger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Infectious Diseases. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.