![]()

1

Strategies

J. Douglas Balcomb

(National Renewable Energy Laboratory, 1617 Cole Boulevard, Golden, CO 80401, USA)

1.1 INTRODUCTION

This part of the book summarizes how energy consumption has been reduced by the IEA Solar Heating and Cooling Programme Task 15 houses (Task 13 house). The strategies that proved to be the most effective for the houses are highlighted and discussed quantitatively, both as a group and individually. The focus is on this group of houses as they were finally designed. Conclusions are drawn based on studying and comparing features common to all or most of the houses.

The reader should note that the numbers quoted in this part are all based on computer simulations made by the individual countries. Thus they are predicted, and not measured, numbers. Initial indications are that measured values are somewhat higher than predictions. Nonetheless, valuable inferences can be drawn from the predictions.

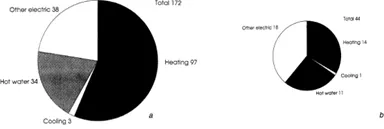

How much energy is predicted for these houses? The smaller pie chart on the right in Figure 1.1.1 shows the average purchased energy for the 14 Task 13 houses. The larger pie chart on the left shows typical values for a contemporary house, averaged over the same countries. The Task 13 houses use 44 kWh/m2 of heated floor area compared to 172 kWh/m2 for the typical house, a 75% reduction. The total solar contribution to these houses averages 37 kWh/m2, including the useful passive solar gains, active solar, and photovoltaics.

Note that throughout this book, energy reported is the actual energy brought into the building. Bear in mind that the source energy required to produce and deliver energy to the dwelling can vary greatly. For example, electricity from a thermal power plant typically requires about three units of source energy to produce one unit of delivered energy compared to gas for which the ratio is more typically 1.3 units of source energy per unit of delivered energy. Another important consideration is that some energy is renewable, including solar, wood, and electricity from hydropower, whereas energy from fossil sources is not.

Although space heat accounts for the largest end use of energy in a typical house in these cold climates, space heat falls second behind electric energy for fans, lights, and appliances in the houses, requiring only 14 kWh/m2 out of the total 44 kWh/m2. On average, these houses use less than 15% of the heating energy of typical houses in each of their countries.

The houses were designed as total systems in which all energy uses were addressed. For example, appliance and lighting consumptions were reduced by selecting efficient units and water-heating consumption was reduced by using either a solar system or by heat recovery. The houses are a most remarkable group offering many instructive lessons for designers in any climate.

1.2 SPACE HEATING REDUCTION

The strategies used to minimize energy needed for space heat are:

- reduce transmission losses by designing a compact, well insulated, and tight envelope

- recover heat from exhaust air

- use passive and active solar gains

- satisfy the remaining heating requirement by producing and using auxiliary heat efficiently.

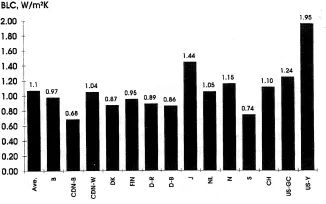

Reduce transmission losses

The Task 13 houses addressed reduction in the gross heating requirement as the first priority. Many of the houses use two or three times more insulation than a typical house. A good indicator of heat transmission is the overall building loss coefficient (BLC). This is the power, in units of watts, required to maintain a temperature difference of IK between the inside and outside of the house.1 The BLC values for the Task 13 houses are shown in Figure 1.2.1. To allow houses of different sizes to be compared, the values are listed per m2 of heated floor area.

Figure 1.1.1. Energy use in (a) typical houses and (b) the Task 13 houses, expressed per rrf of heated floor area

The two houses that stand out as having high BLC values, the Japanese house (J) and the American house in Yosemite (US-Y), are in warmer climates. The average BLC of the remaining 12 houses is 1.0 W/m2K, a good target value for a low-energy house in a cold climate. The variation between the BLC values of these 12 houses, from 0.68 to 1.24 W/m2K, is not particularly large.

There are two ways to achieve a low BLC – design a compact building form to minimize exposed surface area and use high levels of insulation and windows with low U-values. Both are effective and both have been used in the Task 13 houses. The average U-values (in W/m2K) are as follows;

| walls | 0.18 |

| roof | 0.13 |

| windows | 1.24 |

For the U-values achieved in the individual houses, refer to the technology chapters on super insulation (Chapter 2.2) and windows (Chapter 2.3).

Reduce infiltration and ventilation loads

Standards vary, but the amount of fresh air required to maintain adequate indoor air quality ranges between one third and three quarters air changes per hour. The approach to ventilation taken in nearly all of the Task 13 houses is to build the house to be very airtight. Air leakage is held to one tenth or less air changes per hour and then controlled ventilation is provided. There are two advantages to this. First, the ventilation is constant instead of varying from twice the required value to zero, depending on temperature and wind conditions. Second, exhaust air is collected in a single location, allowing heat recovery by either an air-to-air heat exchanger or a heat pump.

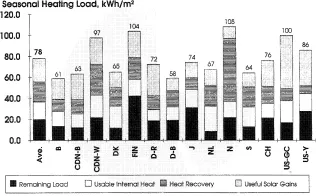

Required heat

Sharply cutting the BLC results in a much reduced annual requirement for heat. Figure 1.2.2 shows the average seasonal heating load of the Task 13 houses. This is total heat from all sources required to maintain 20°C room-temperature comfort from 1 October through 31 March. Note that contributions from internal gains (people, lights, and appliances), heat recovery, passive solar gains, and auxiliary heat are each about one fourth of the total required heat. However, the bars for the Norwegian house (N) and the German house in Berlin (D-B) illustrate that this distribution varies significantly from house to house.

Recover heat

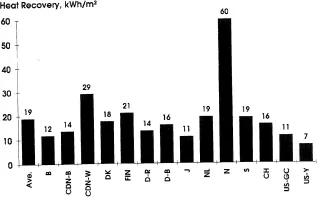

The effectiveness of heat recovery in the Task 13 houses is shown in Figure 1.2.3. The values were determined by running the simulation program twice, first without heat recovery and again with heat recovery, and noting the difference.

On average, heat recovery meets 24% of the space heating requirements of the houses. The high value for the Norwegian house is due to a high ventilation rate of one air change per hour and a very high (theoretical) recovery rate of 90%. Recovery can be done by a heat exchanger which allows cold intake fresh air to be warmed by heat transfer through a partition separating it from the exhaust air. In three of the houses, a heat pump is used to recover heat from exhaust air, and the heat is used to warm hot water or the space, as needed. These techniques are discussed in the respective chapters of Part 2 on Innovative Technologies. A principal advantage of heat recovery is that it works day and night and is effective in any climate.

Figure 1.2.1. Building loss coefficients of the Task 13 houses, normalized by heated floor area

Figure 1.2.2. Space heating requirements of the Task 13 houses, 1 October through 31 March

Figure 1.2.3. Annual heat recovery in the Task 13 houses

Use passive solar gains

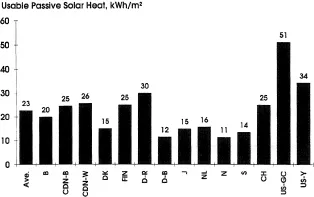

Passive solar heating is an obvious answer in a sunny climate like that of the American house at the Grand Canyon in Arizona (US-GC), a cold climate at 2130 m elevation. It is less obvious at the high latitudes and in the cloudy winter climates of many of the Task 13 houses. The effectiveness of passive solar gains was determined by running the simulation program twice, first without solar gains and again with solar gains, and noting the difference. The results, shown in Figure 1.2.4, indicate a surprisingly high solar contribution, averaging about one third of the total required heat. This exceeds the contribution of the auxiliary heating system. The high values for the houses in the Southwest US are not surprising, but the high solar contribution in the German house in Rottweil (D-R) is impressive in a much less sunny climate.

Figure 1.2.4. Usable passive solar heat in the Task 13 houses

The reason that passive solar heating is effective in the houses at high latitudes is primarily because of the extended length of the heating season. Solar gains are minimal in mid-winter, from December through mid- February, but make a major contribution in the fall and spring seasons, when heating requirements are still substantial.

Four strategies are used to make use of passive solar gains in the Task 13 houses:

- Direct solar gains through windows are an important aspect of all the houses. Unfortunately, in the colder north-latitude climates, window losses are greater than solar gains (taken over the whole heating season) for any type of currently available glazing. But in the range of U-values below 0.8 W/ m2K, windows are close to neutral.

- To increase comfort and the usefulness of solar gains, many of the house interiors include massive materials to store the heat, such as concrete floors and brick walls. The massiveness of the Task 13 houses varies greatly, from the foam insulation panel construction of the US Grand Canyon house to the masonry and concrete construction of the German houses. The Swiss house (CH) is a combination of light exterior walls to maximize insulation and massive interior walls and floors to absorb solar gains. The often-misunderstood role of thermal mass and the recommended minimum amount and placement are further discussed in Chapter 2.8 on Thermal storage.

- Sunspaces are included in five of the houses, the largest being the atrium of the Dutch apartment building (NL). Sunspaces have an amenity value, serve as a buffer space between the living area and the outside, and can be used to preheat ventilation air as described in Chapter 2.7 on Sunspaces.

- A Trombe-Michel wall was included to make up for the low mass of the US Grand Canyon house and balance daytime direct gain. In a Trombe-Michel (or Trombe) wall masonry below the windows is directly warmed by sunlight. In the Task 13 building, heat loss to the outside is hindered by using a selective surface on the wall exterior surface and by two layers of low-iron, high-transmission glass in front of the wall. Solar heat that accumulates in the masonry during the day, is at ...