- 157 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Able Children in Ordinary Schools

About this book

First published in 1997. The purpose of this book is to help teachers of able children in ordinary schools. Very little has been written in Britain about the education of able children, although there is a wide body of research in other parts of the world. What has been written has been primarily from the psychologist's viewpoint or has focused on individual or groups of able children. Such research as has been carried out into provision has focused on selected groups of able children operating in optimum conditions. Both of these elements provide useful information for the teacher but neither is, in itself, sufficient to enable ordinary schools to plan effective provision for their able pupils.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Able Children in Ordinary Schools by Deborah Eyre in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Didattica & Didattica generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Defining Able Children

The education of able pupils in maintained (state) schools since the introduction of comprehensive schools has often been described as the ‘Cinderella’ of education provision. Some educationalists have included able pupils in the category of newly disadvantaged groups. Reasons for this include the lack of legislation concerning the needs and rights of able pupils, the lack of government guidance on effective provision for able pupils at a time when guidance in other areas is extensive, and the lack of nominated funding for staff training or school-based development work. This view emerges from research findings of a range of educational sources. A typical sample is:

In the case of the most able groups the work was considerably less well-matched than for average and less able groups. (HMI, 1978, p.81)

High attainers were underestimated on 40% of tasks assigned to them. (Bennett et al., 1984, p.215)

In the majority of schools the expectations of very able pupils are not sufficiently high. (HMI, 1992, p.28)

However, at the same time as these points are being made by some sectors of the educational establishment, others assert that the whole of the British education system is geared towards meeting the needs of a small percentage of academically able youngsters at the expense of the vast majority of the population. The latter group, in making their case, point to the use of the academically-based GCSE, and the A Level ‘gold standard’ in most school sixth forms. The Dearing 16-19 Review (DfEE, 1996) recognized this academic focus in highlighting the need for a broader range of educational qualifications to reward a wider range of achievements. How then can two such radically differing viewpoints co-exist?

Perhaps the GCSE, which is such a barrier for many pupils, is not in fact sufficiently challenging for the most able. Perhaps the mere existence of such a standard leads schools to focus on gaining A to C grades at GCSE rather than on maximizing the potential of individual pupils. Certainly this whole preoccupation with GCSE does little to affect provision for able pupils in the primary school or even in the early years of the secondary school. Rather than seeing the education system as tilted in favour of the academically able it would be more sensible to view the GCSE issue as a problem related to the existence of an arbitrary measure, of an arbitrary range of subjects and skills, at an arbitrary time in a pupil’s education.

The purposes of this chapter are: to explore the factors that have led to such educational confusion; to consider some of the major issues facing schools as they attempt to define ‘able pupils’; to consider the nature of ability - what we mean by an able child and whether there is educational agreement on this definition; and to explore the link between ability and achievement - are these two terms, often used interchangeably by teachers, the same thing? Unless these issues are carefully considered it is impossible for a school to develop a coherent approach to the nurturing of ability.

Researchers such as Francis Galton (1822–1911) were confident that intelligence was singular, was carried in the head and could be reliably measured by psychometric testing. These ideas of a genetically-inherited superior mind became the basis of the traditionalist view of intelligence. Terman (1925) in the first, and still largest, longitudinal study of gifted children, used psychometric testing as the basis of his selection procedure. During the twentieth century the traditionalist viewpoint has largely been replaced by a wider view of intelligence. Creativity in particular is not measured as part of an intelligence test, but since the work of Guilford (1950) it has come to be recognized by many as an aspect of intelligence. More recently ideas have emerged which suggest that intelligence should be seen as constituting a series of ‘intelligences’ covering a range of components. There are many advocates for this pluralist approach but perhaps the best known to most teachers is Gardner (1983).

IQ as a measure of intelligence

In my experience most people, both teachers and the general public, still hold the view of a single general intelligence (IQ) which children have to a greater or lesser extent and which can be accurately measured on an intelligence test; hence the request from many primary school teachers and parents for an intelligence test to confirm the ability of a child. Frequently teachers say that they think they have an able child in their class but would like an intelligence test administered to confirm their hypothesis.

The fact that such a view remains dominant, at least in England and Wales, is perhaps to some extent a legacy of the 1944 Education Act. This act was rooted firmly in the view that intelligence was inherent and measurable, and that those with different levels of intelligence needed different types of education. Grammar schools, secondary modern schools and technical schools were established to meet the needs of children with different levels of intelligence. The reasons for the dismantling of this system and the introduction of comprehensive schools were, at least in part, a recognition of the system’s failure. There were without doubt some issues related to inequality of funding between types of schools, but a major educational reason was the inaccuracy of the 11+ examination. Famous examples exist of pupils rejected as unsuitable for grammar school who went on to gain doctorates at university or become highly successful in their chosen sphere. Either the 11+ had failed to measure intelligence accurately or an intelligence quotient could change as a child developed.

Many teachers recognize these historical flaws but see them as related to borderline grammar school entrants, not to problems with the selection of able pupils. They continue to believe that it is possible to define a child’s level of ability by the use of a test and to give it a numerical score. Perhaps this is because traditionally the causes of learning deficits have been identified through the use of tests, or perhaps it is simply part of an unrealistic search for an ideal way to categorize children.

Individual teachers are, however, not alone in their continuing faith in the IQ system. Some psychologists still believe that it is possible to measure intelligence through psychometric testing and they continue to seek more accurate measures, e.g. Jensen (1980), Eysenck (1981) and Bouchard et al. (1990). The American Gifted Children programmes in many states relied on psychometric testing for selection until well into the 1980s and some still use them. In England, MENSA has remained a high-profile advocate of intelligence testing and a new association, Children of High Intelligence (CHI) has been formed for children with high IQs. The National Association for Gifted Children (NAGC), a parental pressure group, until very recently advocated better provision for gifted children in schools, based on a single intelligence platform.

However, the main body of research into intelligence indicates that the link between high IQ and high achievement is under review Freeman (1995, p. 15) states:

The assumption that a high IQ is essential for outstanding achievement is giving way to recognition of the vital role of support and example, knowledge acquisition, and personal attributes such as motivation, self-discipline, curiosity, and a drive for autonomy - all this being present at the right developmental time.

A multi-dimensional view of ability

The vast majority of psychologists in the second half of the twentieth century see ability as being made up of a number of factors. In the first place, traditional ideas of ability being linked only to cognitive domains and their development in school have given way to a focus on a broader range of abilities (music, art, sport) and to a consideration of lifelong learning and achievement. Even within the cognitive range it is now accepted that elements in addition to IQ, such as creativity, are important. Also, the achievements of a child in school are not always reflected in later performance. For some children conditions at school or in their home life may mean that they do not fulfil their potential during conventional schooling. Equally, these may lead to lower or accelerated performance at certain times in the child’s school career.

Ability in art, sport or music has come to be recognized as comparable with cognitive ability and in equal need of nurturing. If a school is looking to identify those with cognitive abilities they should also consider those with ability in music, art and sport.

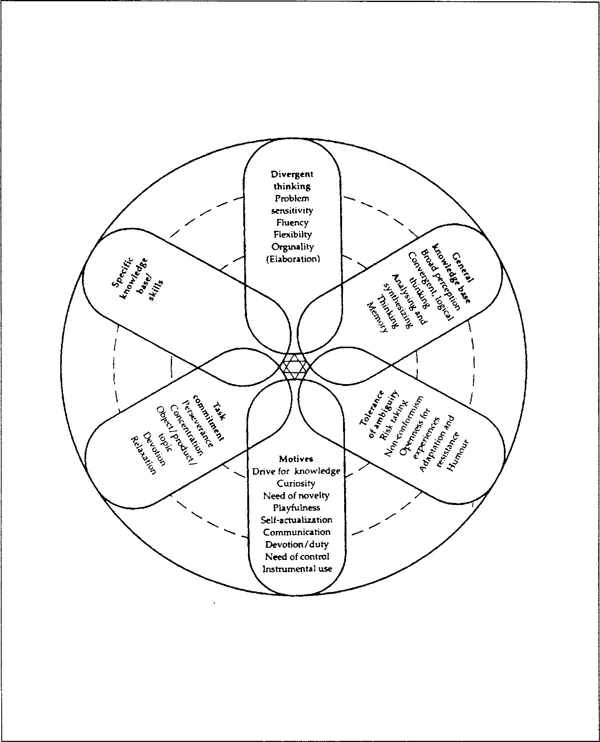

In defining a multi-dimensional view of giftedness, simple ideas have given way to increasingly complex ones. Creativity, since the work of Guilford (1950), has been seen by many psychologists as an essential aspect of giftedness. It is the component which differentiates between those who do well and those who do brilliantly Sternberg (1985), Cropley (1995) and Urban (1990) are all leading figures in this field. Psychologists with an interest in creativity have tried both to define it and to measure it. Urban’s model of creativity (Figure 1.1) illustrates well the complexity in this single component.

Figure 1.1 Urban’s component model of creativity

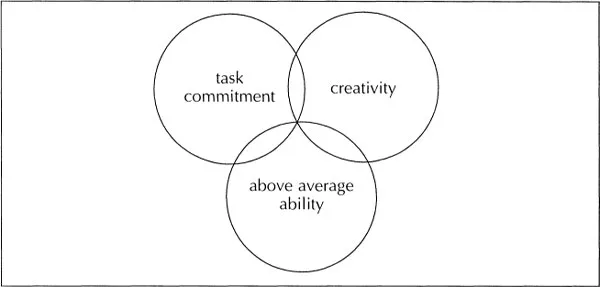

Renzulli (1977) defined giftedness more widely by suggesting that it included not only ability and creativity but also task commitment (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2 Renzulli rings

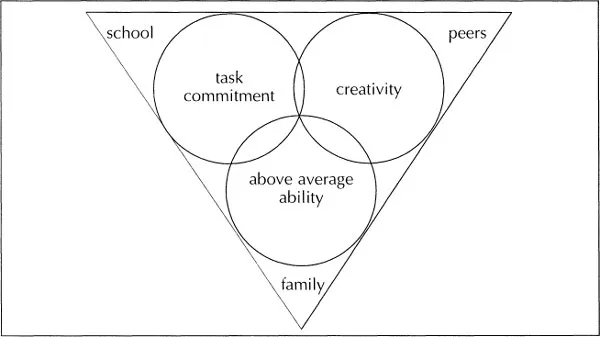

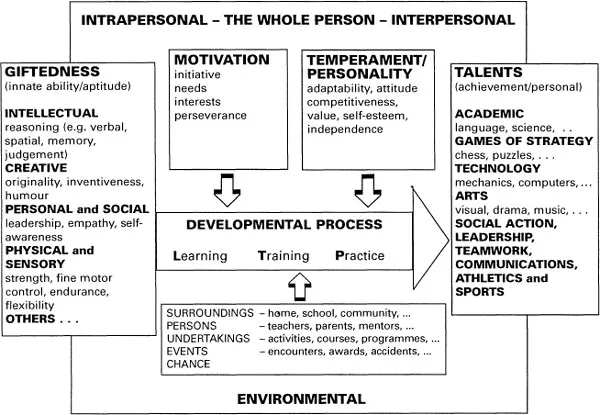

Sternberg (1985) put forward his ‘triarchic theory’ which included componential, experimental and contextual elements. Monks (1992, see Figure 1.3), Gagn’ (1994, see Figure 1.4) and others have added the influence of home, school and peers — the element of opportunity and support which seems to be so influential in converting potential into achievement.

Figure 1.3 A multifactional model of giftedness (Monks, 1992)

Figure 1.4 Gagné’s modified model for the more able and exceptionally able

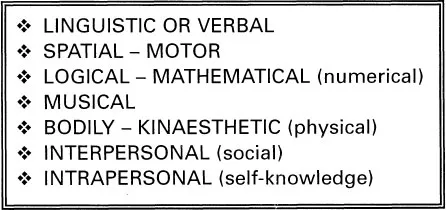

Finally, one should mention the work of Gardner (1983), with his focus on multiple intelligences: ‘Genius is likely to be specific to particular contexts: human beings have evolved to exhibit several intelligences and not draw variously on one flexible intelligence’. Gardner recognizes seven relatively autonomous forms of ability (see Figure 1.5, Krechevsky and Gardner, 1990). A child may be able in any one or any combination of these: just because a child excels in one area it is not obvious that he or she will excel in others.

Figure 1.5 Multiple intelligences

For those of us whose interest in this area lies in the implications for schools, the array of research may at first be daunting. No wonder a simple test of IQ seems more appealing to some. However, the really important implication for schools is simple: ability is complex, it is made up of a range of factors, some of which it is impossible to measure effectively. If a school uses a broad definition of ability (encompassing not only ability in academic subjects but also in art, music and sport) and it recognizes the role of creativity, motivation and opportunity, then its methods for the identification and nurturing of such ability will be complex.

The link between ability and achievement

In recent years there have been several retrospective studies looking at the early lives of people who went on to become high achievers. Bloom (1985) considered the top 200 Americans in a range of specialisms, from mathematics to swimming, music to brain surgery. Howe (1995) looked at the early lives of geniuses. Evidence from these kinds of studies began to indicate that many high achievers did not show outstanding ability or precocious talent in early life. Therefore the search for a test of reliable indicators of ability in early childhood may prove of limited value in terms of determining future success.

These findings are of immense significance for teachers and educators. They mean that a child’s performance at age 5, as judged against the mean, may be very different from a child’s performance at 11 or 14. Schools consistently expect children to develop at an even pace and, although teachers are aware of the possibility of late development, etc., the organizational systems rarely take account of this. The top group or set often remains the same and the most able pupils who are identified at entry to secondary school in Year 7 often remain the most able cohort throughout their time at the school.

From the point of view of the individual child this is an interesting area. There are without doubt significant numbers of children who do not show outstanding talent in the early years but who go on to achieve highly at GCSE and A Level. They may not be among the best mathematicians in the class, but may later go on to outstrip them in terms of performance. They may be slow to develop the secretarial skills of writing and punctuation but later develop a style of great maturity. Equally, there are children who at age 5 appear to be exceptional in their ability but who seem to plateau out by the end of the primary school. Observing this across a whole LEA, I at first attributed this decline in performance to the teaching and opportunities in Key Stage 2 (7-11 years). Further investigation suggests a different and more complex conclusion linked to motivation, opportunities and parental influence.

What makes success

There seem to be three separate components which tog...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Preface

- Chapter 1 Defining Able Children

- Chapter 2 Identification

- Chapter 3 A Differentiated Approach to Classroom Planning

- Chapter 4 Classroom Provision

- Chapter 5 Issues for Secondary Schools

- Chapter 6 Issues for Primary Schools

- Appendix 1 Writing a Policy for the More Able

- Appendix 2 Marston Middle School, Oxford: Policy for Able Pupils

- Bibliography

- Index