- 370 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Public Policy Making Reexamined

About this book

Public Policymaking Reexamined is now recognized as a fundamental treatise for public policy studies. Although it caused much controversy when it was first published for its systematic approach to policy studies, the book is acknowledged as a modern classic of continuing importance for the teaching and research of public policy, planning and policy analysis, and public administration. The paperback includes a new introduction updating and supplementing many of the author's original ideas.Professor Dror combines the approaches of policy analysis, behavioral science, and systems analysis in his examination of the reality of public policymaking and his suggestions for its reform. Actual policymaking is carefully evaluated with the help of explicit criteria and standards based on an optimal model approach, resulting in detailed proposals for improvement. He applies a scientific orientation to the study of social facts and theory.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Public Policy Making Reexamined by Yehezkel Dror in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

THE MISSION

THE MISSION

chapter 1. The Problem and Its Setting

The major problem with contemporary public policymaking is the constantly widening gap between what is known about policymaking and how policy is actually made. Contemporary societies, faced with critical problems whose solutions will require the utmost skill, rely on outmoded policymaking machinery. Corporations, private institutions, government organizations, all need to have their decisionmaking tools continually improved.

Correlation Between Knowledge and Power

Information relevant to public policymaking is becoming more and more available. How can this information be introduced into the policy-making process so as to increase the correlation between knowledge and power? This problem, in one form or another, has been known since Plato's Republic. Its solution is now critical because unwise policies, hastily or laboriously “muddled through” by “rules-of-thumb” or some similar time-honored method, can now have unprecedentedly grave consequences. For the first time in history, it is possible to examine the characteristics and causal variables of public policymaking explicitly and systematically, and to institute a reform of public policymaking based in part on such explicit examination and on scientific criteria. Such a reform, however, will probably have to be rather revolutionary, and will probably not be easily accepted.

For many years our technological knowledge has been rapidly outpacing our decisionmaking institutions. (This fact has often been pointed out; it has frequently been overstated.) Until the nineteenth century, society usually showed great capacity for assimilating new scientific and technological information and putting it to rather wide use. Among the novel social adjustments to new knowledge were, for example, the limited-liability corporation, central planning units, the mass-democratic state, independent regulatory commissions, and professional managers. However, the technologies and theories of most of the older scientific knowledge did not deal directly with the central institutions and values of society (perhaps partly because a lack of autonomy, or of freedom of inquiry, kept findings that contradicted such basic institutions and values from being recognized). It is modern science that has made the relationship between knowledge and social action a radical problem. It not only has made very high-quality public policymaking necessary, but has also provided some of the knowledge needed to achieve such policymaking.

Science as Creator of Problems

That modern science both creates problems and provides better means for solving them is a striking phenomenon. I will leave exploring the metaphysics of such fascinating symmetry for some other time, and limit myself here to discussing the facts that seem to be emerging. First I want to consider some questions that are raised by science's creating new and critical problems or aggravating old ones, especially the two questions: how can the potential benefits of new knowledge be put to good use, and how can the catastrophes that can follow from their misuse be prevented?

The most dramatic and obvious form of the latter question is one we are now facing: how can we prevent nuclear war? Conflict and war have always been characteristics of human society, and will continue to be so in the foreseeable future, but now they endanger the survival of modern civilization, and perhaps of humanity as a whole, because of advances in the technologies of violence. This problem will become increasingly difficult to solve in the future, when wide use of nuclear power plants, and cheaper methods of nuclear engineering, will increase the number of states (perhaps even smaller social groups) with their own nuclear or biochemical weapons, and thus the chances of universal disaster brought about by accident, recklessness, or design.

Problems posed by developments in genetics, birth control, mass communication, and production methods are less dramatic than those posed by nuclear technology, but are in the long run no less significant. The problems of space travel will also require not only much high-quality engineering, but, even more, increasingly complex organizations able to perform better policymaking. Some other critical problems are: modernizing the “developing” states, which today include most of mankind; meeting threats to world order that are shaped by technologies of violence and communication, but are rooted in deeper ideological and social issues; resolving inequities in the balance of power and in the division of functions between individuals and various organizations in modern mass societies; facing the social implications of rapid increases in production, consumption, and leisure time; and achieving a quantitative and qualitative balance between population and resources.

Many of these problems have been around since the dawn of history, but have assumed their present proportions only since the advent of modern science. Modem science has also been a major force in disjointing traditional relationships between social institutions, belief systems, and knowledge. The technological innovations that first disturbed traditional behavior patterns were changes in production technology, hygiene and medicine, and communications, but findings that have undermined the values and assumptions of basic social institutions (theories of evolution, genetics, and depth psychology, for example) have been even more disruptive. Some examples of such problems are: the imbalance between production potential and effective demand in many modern states, which may become worse as the industrial trend toward automation accelerates; fundamental issues that space travel may pose for the major religions and for human thought in general; and the acute collision between modern technology and traditional social structures in most of the developing nations.

Extrapolating from present trends, I can see only a continuously accelerating rate of innovation in most branches of science. The knowledge these innovations will create will be able either to destroy mankind physically and socially or, if it is used to our best advantage, to lift mankind to new heights of individual and social existence. The problem of integrating knowledge and social action is therefore becoming both more difficult and more critical. Conscious calculation of social direction must therefore partly replace the automatic and semispontaneous adjustment of society to new knowledge that generally sufficed in the past.

Some Possible Solutions

There are several ways new knowledge could possibly be better integrated into society. One would be to try to achieve a working equilibrium by explicitly limiting the freedom of scientific research, so as to forestall or contain new findings that might endanger society either physically or by undermining too many of its basic values. This solution seems a priori both infeasible and undesirable. The cold-war situation demands exactly that knowledge which could be physically disastrous, and western democratic ideology favors unrestrained scientific activity. Nevertheless, the possibility of controlling scientific activity is important, and in some areas may be essential and acceptable. For instance, an agreement to control nuclear armament is not very useful if it does not also prevent the development of a technology that could enable small countries to manufacture nuclear bombs surreptitiously. Public opinion in western democratic countries may also support restraining research on doomsday machines or mass biocontrol(that is, controlling emotions and perceptions by external signals), mass hypnosis, or similar mass opinion-shaping devices.

Another possibility would be to limit the dissemination of knowledge whose widespread availability might be physically or culturally dangerous. This solution is also formally rejected by contemporary western ideology, which regards all knowledge as being nearly always “good.” Nevertheless, and luckily enough, knowledge is in fact often disseminated in channels that tend to keep it from persons who might misuse it or be harmed by it. Information about toxicology is not now readily available to criminals. Another case in point is that many assumptions of mass-democratic ideology have been rather clearly refuted by most studies of political behavior. The myth of the intelligent and autonomous voter does not square very well with empiric studies of voting behavior. Knowledge of such studies is still (in 1967) limited to specialized groups. Widespread knowledge of these studies' findings might well undermine beliefs that help maintain democracy and might generate a mass cynicism that could only be dissipated if the people could be led to accept a more sophisticated theory of democracy.

The last remarks point to a third solution, namely, to reform social institutions and culture in the light of new knowledge. This solution is the one most acceptable to contemporary ideologies, but it presents a major difficulty. How much do the characteristics of the new knowledge and of contemporary society allow them to be successfully integrated by changes in social institutions and in culture?

One conclusion seems inescapable: the problems faced even now by modern society, to say nothing of the problems scientific progress and social evolution will raise in the foreseeable future, require very high-quality public policymaking for even minimally satisfactory solutions.

Toward a Policy Science

Modem science creates both problems and means for solving them, if (and this is a big if) those means are put to their best use. Science cannot answer the spiritual problems of human life, eliminate conflict and personal suffering, determine final values and beliefs, or solve problems “once and for all.”1 Furthermore, I make no claim that science will completely replace intuition, hunches, tacit knowledge, insights bom of experience, or bathtub “Eurekas.” All I claim is that in the future much more scientific knowledge will be available, that it will be directly relevant to policymaking about social issues and to social self-direction, and that it will have to be used to the fullest if present and future social problems are going to be adequately solved.

This new knowledge will not be limited to the instrumental aspects of social action, as the physical sciences and most of the life sciences are, but will deal with the core processes and structure of public policymaking itself. One of my major hypotheses is that we can develop a policy science that will significantly improve the quality of public policymaking if it is fully used. That this new discipline is becoming possible is shown by the increases in knowledge about the very processes by which human beings and human society grow and operate, about decisionmaking processes, decisionmaking systems, and systems analysis and design, and about complex decisionmaking and intelligence-amplifying machines.

The word “science” here carries certain positive connotations that the reader should not allow to impair his critical consideration of my subject matter. I would almost prefer to use the term “study,” which might better describe both the inherent nature of, and the present state of knowledge in, the social “sciences,” the decisionmaking “sciences,” and policy “science.”

To clarify my argument, I must distinguish between knowledge that is relevant to devising a given policy, and knowledge that is relevant to policymaking. Certain types of knowledge are relevant to substantive policy issues. For instance, some medical knowledge is relevant to policies about public health; some sociological knowledge is relevant to policies about social segregation; some historical knowledge is relevant to policies about external relations; and so on. Hereafter I will use the term policy-issue knowledge to refer to knowledge pertinent to a specific policy.

Policymaking knowledge is one step further removed from discrete policy issues. It deals with the policymaking system, with how it operates and how it can be improved. Available policymaking knowledge deals, for instance, with: how organizational structures operate (organization theory); ways to improve the quality of the people engaged in policy-making (personnel development); collecting and using information (intelligence studies and information theory); coordinating and integrating different policymaking units (political science); designing better decisions (operations research and decision sciences); analyzing, improving, and managing complex systems (systems theory). To cover the complex of theory and information dealing with policymaking as a process (as distinct from that relevant to specific policies), I will use the term policymaking knowledge. In essence, policymaking knowledge deals with the problem of how to make policy about making policies. That is, policymaking knowledge dealing with metapolicy. For convenience, I will use the term policy knowledge to refer to both policy-issue knowledge and policymaking knowledge. Policy science can therefore be partly described as the discipline that searches for policy knowledge, that seeks general policy-issue knowledge and policymaking knowledge, and integrates them into a distinct study.

The major problem at which policy science is directed is how to improve the design and operations of policymaking systems. A major component of this problem is how to increase the role of policy-issue knowledge in policymaking on concrete issues. For example, new sociological knowledge is relevant to more and more social problems, such as containing social aggression and using leisure time. But if the policymaking system is to use this policy-issue knowledge, changes must be made in the system. For example, sociologists might have to be appointed to staff positions in most of the main policymaking organizations, and new process patterns would have to be introduced to assure that these advisors actually participated in policymaking.

Another major component of the problem is how to increase the role of policymaking knowledge in the operation of the policymaking system and in improving it. For example, modern decision sciences establish the best methods for dealing with certain quantifiable problems. To use that information in policymaking, other changes would have to be made in the policymaking system; policymaking activities would have to be systematically screened to identify those that could even partially be handled by quantitative methods, and personnel and an organization able to use these methods would have to be set up. Even more complicated changes in the policymaking system could be required, for example, by new knowledge from psychology and organization theory about conditions that encourage creativity.

Basic Theses

Although I will continue discussing the central problems I have mentioned above throughout this book, I can now set forth my basic theses about such problems in the form of five propositions:

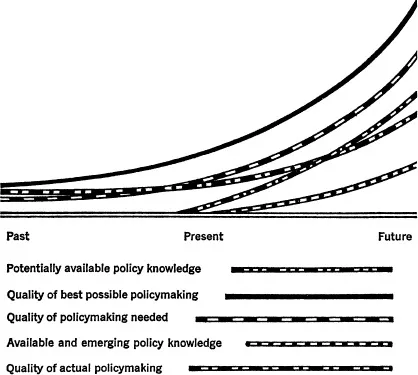

- 1. The scientific revolution, and the transformations it has caused in social structures and in the heights to which men can aspire, together with other changes in culture and society, have made continual improvement of public policymaking necessary if such policymaking is to lead to satisfactory results and progress, or, perhaps, is even to assure survival.

- 2. The amount of available policy knowledge is increasing, and so is its quality.

- 3. The quality of the best possible policymaking increases as a function of increases in available policy knowledge.

- 4. The quality of actual public policymaking improves much more slowly because there are barriers against the improvement of policymaking reality.

- 5. As a result, actual public policymaking falls farther below both what it could be and what it must be. (See Fig. 1.)

FIGURE 1 BASIC TRENDS AFFECTING POLICYMAKING QUALITY

The development of policy science must be speeded up, and this advanced policy science put to its fullest use, if critical problems are to be adequately solved. But the many changes that will ha...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- References

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Part I. The Mission

- Part II. A Framework for Evaluating Public Policymaking

- Part III. A Diagnostic Evaluation of Contemporary Public Policymaking

- Part IV. An Optimal Model of Public Policymaking

- Part V. On Improving Public Policymaking

- Part VI. The Choice: Shaping the Future or Muddling Through