![]()

Part I

The distinctive theoretical features of ACC

![]()

1

The world according to ACC

For many coachees, especially those in the business world, the Acceptance and Commitment Coaching (ACC) approach feels like a radical departure. They, like almost all of us, have been raised to believe a number of things about life and how to navigate it. For instance, one overwhelmingly popular belief – if not always expressed in exactly these terms – is that the key to fulfilment in life is to avoid discomfort and pursue “happiness”. When an attempt is made to define what is meant by happiness, it is normally described as a state where pleasant feelings and thoughts outnumber unpleasant feelings and thoughts.

A further belief – one that is popular in the Western world in general, but particularly fuels the worlds of business and sport – is that the achievement of “success” is the most reliable means of banishing unpleasant internal experiences and achieving happiness. In this context, success is often equated with status, influence, material reward and affirmation and esteem from others.

You can see how the combination of these two beliefs can tie people up in knots: perpetually chasing a definition of success almost entirely defined by factors external to the self, in pursuit of a state – “happiness” – which is by its nature ephemeral.

The ACC philosophy, while sometimes exploring ideas of the self and involving the kind of meditative exercises that can initially be met with scepticism, is determinedly pragmatic. It posits that uncomfortable, unwanted thoughts and feelings are an inevitable part of life; indeed, that a life that is fully lived, rich, fun and fulfilling will necessarily involve willingly exposing oneself to this stuff. It also acknowledges that, as human beings, we are pretty much hard-wired to avoid unpleasant internal events. This natural inclination, and its limitations as a means of navigating through life, is beautifully captured in the story of “The Bear and the Blueberry Bush”.

Imagine you are following a path through a forest. You have been following the path for several hours and you are not 100% sure where you are going. Already on the journey there have been some really cool, fun moments – things you’ve seen that have been weird and beautiful. But there have been some unpleasant moments too – stuff that has been scary, and at times you’ve felt completely lost. Right now you know that you are a little bit tired and very hungry …

Then you come to a fork in the path – it splits off in two directions. When you look down one path you see, bathed in sunlight, a tall, lush, wild blueberry bush. When you look down the other path you see, snarling from the shadows, an enormous, hulking, grizzly bear. Which path do you choose?

Naturally, almost everybody who considers this question will choose the path with the blueberry bush. It’s no more than common sense from an evolutionary perspective. We have evolved to avoid things that are or feel threatening, while moving towards those that offer safety and security and nourishment. This has helped us to survive and prosper as a species, and remains a helpful guiding principle when applied to the external world. But it becomes a trap when we apply it too rigidly to our internal worlds – the world of thoughts, feelings, memories and sensations. If we always avoid situations that are challenging, a bit scary or that take us out of our comfort zones, our lives become very limited. Sure, it works in the short term – there is a sense of relief in not having to put up with those horrible thoughts and feelings. But in the long term? Nothing changes. You don’t connect, you don’t do the stuff that matters most, you don’t grow or develop or push yourself.

The role of the ACC coach is to propose to our coachees that it is not the presence of unwelcome thoughts and feelings that is problematic and that derails us in life, it is the way that we tend to respond to them. It is the impulse to push them away, deny them, struggle with them or avoid situations in which they might be evoked that keeps us stuck. In addition to this, our role is then to help them develop their psychological flexibility.

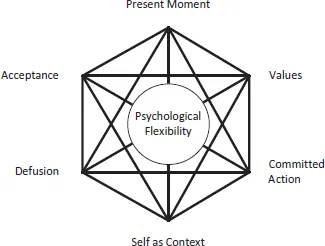

Psychological flexibility is the ability to fully connect with the present moment in order to engage behavioural patterns supporting movement towards valued ends. It is comprised of six processes: acceptance, defusion, contact with the present moment, self-as-context, values and committed action. These processes are set out visually in a hexagon, also known as the Hexaflex (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 The ACT Hexaflex

As coaches we will be working with people who want more from their lives in some way – where they are now is not where they want to be. Perhaps they want to develop as leaders at work; perhaps they want to forge a new career entirely; perhaps they want to improve their performance in a sport or physical pursuit; perhaps they want to find a better balance between work life and personal life. For them, changing will mean stepping into the unknown, and doing that is bound to provoke some challenging or uncomfortable thoughts and feelings. The ACC approach is to consider these thoughts and feelings entirely normal and healthy. Indeed, they can be seen as “the price of admission” to a life that is rich, fulfilling, fun, challenging and fully lived. As you will see, a growing body of research suggests that helping coachees to develop their psychological flexibility is a proven, effective way of enabling them to consciously move towards their goals and values.

![]()

2

Why ACC?

From being a relatively uncommon intervention only a couple of decades ago, coaching is now a well-established discipline in multiple areas. Health and wellness coaching, career coaching and, in particular, business and executive coaching are rapidly growing in terms of popularity and professional credibility. A 2016 study by the International Coach Federation (ICF) estimated that there were approximately 53,000 professional coach practitioners worldwide, with a global revenue from coaching of over US$2 billion per year.

This rapid growth is based on an emerging body of anecdotal and research evidence attesting to the effectiveness of coaching. On this basis, what is the need for ACC? Isn’t the coaching world doing fine without it? Perhaps, but along with the growing profile of coaching will continue to come a growing necessity for regulation, professionalism and scientific rigour. As we will explain in Chapter 4 (ACT coaching research), this is an area where ACC offers something that is absent elsewhere in the coaching world.

Fillery-Travis and Lane (2006) concluded that answering the question “does it work?” is no longer enough, and that it is now time to shift to “how does it work?”. While one of the strengths of the coaching approach has been its willingness to borrow and learn from other models and psychological disciplines, the fact is that this means that most coaches are not using theoretically consistent techniques or measures. As a result, the question “how does it work?” has not been satisfactorily answered.

ACC has an answer. Pioneered by the likes of Rachel Skews, Rachel Collis, Richard Blonna, Rob Archer and Tim Anstiss, ACC is based on the principles of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT). As such, it has a clear theoretical underpinning through which we can understand the underlying mechanisms and processes of any change that occurs. The focus is clearly on how language and thinking influence human behaviour, and how the development of psychological flexibility can enable coachees to make significant and sustainable steps in the direction of their values. This coherent model of human behaviour means that there is a clarity and consistency to coaching sessions in terms of context and focus, if not content and structure.

Indeed, the theoretical basis offers a clear and robust framework within which the coach can exercise creativity and collaborate freely with their coachee. ACC is by its nature experiential, which lends it to interesting, engaging coaching interactions. Many find it to be a refreshing departure from the highly verbal counselling style of interaction that many expect or have experienced previously in coaching.

Here, the underlying theory of Relational Frame Theory (see Chapter 3, Relational Frame Theory for dummies) actually informs the nature of the coaching interaction, in that it emphasises direct, experiential learning over verbal instruction. This promotes the use of creative exercises, metaphors and interactions that are designed to enrich coachees’ understanding of their inner worlds and the interaction between their behaviour and the outside world. As a result, there is often an added level of dynamism and experiential immersion to the coaching interaction.

Perhaps surprisingly, given that it has its roots in clinical practice, ACT is uniquely suited to coaching, and the transition to ACC has been simple. It is based on language-based learning processes fundamental to all human functioning, rather than a model of deficit or disability. Simply put, the assumption is that the coachee is not broken, in need of fixing, but simply struggling with the way that we as humans tend to respond to the language-machine of the mind. It is this struggle that underpins any problem that a coachee might be experiencing. Coaches often refer to themselves as process, rather than content experts. A coach doesn’t need to be an expert in the field their coachee works in or the area in which they wish to make change; their role is simply to facilitate and promote this process of change. The versatile nature of ACC is perfectly suited to this. It doesn’t matter what issue the coachee presents with, or what industry they work in. The ACC coach’s job is simply to help them develop their psychological flexibility, and we can trust that values-based change will follow.

Which brings us to the final point we would wish to make in addressing the question “why Acceptance and Commitment Coaching?”. The model itself is inherently humanistic, compassionate and optimistic. It is based on the assumption that as human beings each of us has a set of values, a core purpose; one that can get lost in the swirl of thoughts, feelings and judgements that are an inevitable part of the human experience. And yet, even when these thoughts seem overwhelming, when the feelings seem unbearable, it is possible to connect with these values and take action to live a life of meaning. At its best, ACC is not just effective in terms of behaviour change, it is personally empowering and ennobling.

References

Fillery-Travis, A., & Lane, D. (2006). Does coaching work or are we asking the wrong question? International Coaching Psychology Review, 1, 23–35.

International Coaching Federation. (2016). ICF global coaching study. Retrieved from https://coachfederation.org/app/uploads/2017/12/2016ICFGlobalCoachingStudy_ExecutiveSummary-2.pdf

![]()

3

Relational Frame Theory for dummies

Learning to play an instrument normally happens through a combination of instruction by someone else and practice. Eventually you become competent and may even master your instrument. In learning, it’s not a requirement to know how to read sheet music, but it can dramatically open up different ways of learning new pieces of music and ways to play your instrument. This is how Relational Frame Theory (RFT) fits into ACC. We would propose that a good understanding of ACT is plenty good enough for 90% of coaching situations. But to expand your practice, it’s helpful to have an understanding to the fundamentals behind the model.

A significant proportion of modern psychological approaches has its roots in behaviourism, an approach pioneered by the famous and famously named Burrhus Frederic Skinner. At its heart, behaviourism said that every action we take is dependent on previous actions and their consequences. If the consequences of an action were not so good, the behaviour became less likely to be repeated. If they were good, it became more likely. This describes the principle of reinforcement within a framework of learning called operant conditioning. These principles have enormous applicability to every sphere of human activity.

The one arena that behaviourism and Skinner failed to crack was that most important area of languaging. This is the very activity you are engaging in right now – making sense of these funny scratchy inky symbols, stamped onto sheets of paper or electronic device, as we attempt, using these symbols, to communicate to you in a meaningful way. Language allows us to communicate our desires and wishes efficiently without relying on random hoots and grunts. It gives us a way to recall events from the past. It allows us the tools to anticipate the future. Collectively, it hugely increases our opportunity to cooperate, on a scale seldom seen in the natural world.

Skinner had attempted to provide an account of human verbal behaviour (Skinner, 1957), but was heavily criticised for not being able to address one of its key features, its generativity (Chomsky, 1959). Generativity accounts for the explosion of language learning that happens with infants. It’s nearly as if they come pre-programmed to learn language, and in a certain way they do. While Skinner’s behavioural principles were unable to account for emergent (untrained or derived) responses, RFT does (Hayes, Barnes-Holmes & Roches, 2001).

RFT proposes that our language abilities are learned and we learn to relate objects, concepts or ideas to each other. This type of learning is known as arbitrarily applicable derived relational responding. At its core, it states that we learn to relate objects, concepts or ideas to each other using different “frames”. Frames can include “same” (this book is the same as that book) or “different” (I am different from you). Frames can also relate using time (now or then) and space (here or there). We can frame events mutually; for example, the sun is bigger than the moon, which, in this context, confers largeness on to the sun, and smallness on to the moon. But, given a cue, we can relate in combination; the gal...