- 152 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Voice and Speech in the Theatre

About this book

This is a classic book on voice and speech, designed for actors at all levels. One of the great voice teachers of his day, J. Clifford Turner here uses simple and direct language to impart the necessary technical 'basics' of speech and voice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Voice and Speech in the Theatre by J. Clifford Turner,Malcolm Morrison in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Performing Arts. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Subtopic

Performing Arts1 • THE VOICE IN THEORY

When the technical equipment of the actor is considered, voice and speech are of paramount importance. The actor’s art, it is true, consists of much more than the delivery of the lines, but take away the element of voice and very little is left. Even if the actor were to forget the aesthetic implications of his or her craft, mere economics compel perfection and care of the voice, and the acquisition of control over speech. It may be retorted that some actors have succeeded in spite of poor or indifferent vocal equipment, and that others have successfully capitalized peculiar individualities of voice and diction. The very highest manifestations of any art are always characterized by a technique so flawless that it is unnoticeable and becomes one with the art itself. This book is not addressed to those whose aim is to exploit their peculiarities. There is a place in the theatre for voices of many types, but no room whatsoever for any voice that is incorrectly managed, or for voice and speech which is not appropriate to the play.

VOICE AND SPEECH AS A HABIT

Voice is instinctive and speech is an acquired habit. The child does not have to learn how to cry and croon, but speech is the result of much laborious experiment, which is forgotten as soon as the movements of the tongue and lips have been repeated a sufficient number of times to set up a habit.

THE RESULTS OF CONDITIONING

Both voice and speech are conditioned by a large number of factors, for example the influence of social and regional environment. No two persons have identical voices, although many have family resemblances, but there are many who make use of identical speech movements.

The actor makes use of the gift of voice and the acquired habit of speech, and some degree of proficiency in the day-to-day use of both has always been obtained before they are employed in the theatre. It is clearly not so with the other arts. In these, the acquisition of a technique is obvious, and the habits that are thereby acquired are conditioned entirely by the art. Voice and speech for the majority are haphazard affairs, but what passes in everyday life will not stand the test of performance in the theatre, and the qualities that are essential for the actor cannot be acquired overnight, let alone during the process of rehearsal. The voice and speech of the embryo actor, then, are already determined before acting begins. Unfortunately, difficulties often arise when bad habits have to be discarded and prejudices overcome before the new habits can be substituted. In many ways it would be simpler for all concerned were he or she in a position to start from scratch.

The text of a play has often most aptly been compared with a musical score. The actor is the link between the dramatist and the audience. The voice is the means by which the dramatist’s work is bodied forth, and is the main channel along which thought and feeling are to flow. The voice, in fact, is an instrument, a highly specialized instrument, which is activated and played upon by the actors intelligence and feeling, both of which have been stimulated by the imaginative power he or she is able to bring to bear upon the dramatist’s creation. The actor not only has a most rigorous standard of integrity to which he or she must adhere, but bears a definite responsibility to the dramatist, the director, fellow actors, and the audience.

THE VOICE AS AN INSTRUMENT

Once this is admitted, it is obvious that the most exacting demands are made upon the voice, which is capable of achieving its objectives only when it has become a responsive instrument capable of great refinement of detail. This attitude towards the matter may be likened to the relationship which exists between a musician and the instrument. Supreme moments are achieved only when there is a balance held between the instrument and the person who plays it, and when both contribute equally, for the virtuoso will be hampered by an indifferent instrument, and the tyro will achieve but meagre results from the most sensitive instrument. The two are complementary. And so it is with the actor. Even the most brilliant intellectual and emotional grasp of character and situation will be diminished in effect by poor vocal equipment, and mere voice, whether ‘full of sound and fury’ or not, will signify next to nothing.

The aim of this book is to indicate the fundamentals of training which will put at the actors command a technique of voice and speech; a technique which will embody the essentials of the art, but which cannot in the nature of things be in any way final or conclusive.

A technique matures only with the development and maturing of the imagination by which it is controlled and whose servant it is.

THE PRODUCTION OF VOICE

When the term voice is used it refers to the quality of the tone by which a speaker may be identified. But tone pre-supposes a resonator, and a resonator is lifeless and inert until it is activated, and only then are its properties heard. To understand the voice in its essentials, we must understand the importance of a whole sequence of events which must take place before tone results. Before the tone of an instrument such as the violin is heard, the strings must be bowed. The energy of the arm movements is transferred to the strings, which then vibrate, and so set up a note. This note acquires tone through the resonating properties of the wooden belly of the instrument.

Excitor, vibrator, resonator

There are thus three separate and distinct factors to be taken into account–

1. The Excitor: the force which is essential to initiate any sound. The energy behind the arm movements of the violinist and the drummer. The breath of the oboe player.

2. The Vibrator: that part of the instrument which resists the excitor, or to which the energy of the excitor is transferred. The strings of the violin, the stretched skin of the drum, the reed of the oboe.

3. The Resonator: that part of the instrument which amplifies the note resulting from bringing the excitor and vibrator into association. The wooden part beneath the strings of the violin, and the whole of woodwind and brass instruments into which the reed is inserted or into the mouthpiece of which the player blows.

In a violin, as in many other man-made instruments, the tone is determined by the skill of the craftsman who makes the instrument. The instrumentalist, although initially concerned with the setting up of a note which will do nothing to destroy or mar the tone of which the resonator is capable, is primarily concerned with the movements which the particular instrument demands to render the printed score in terms of sound.

VOICE AS A SECONDARY ACTIVITY

The genius of man has enabled him to adapt the function of a number of bodily organs to achieve the same results. This function of the organs is only secondary to their main and vital functions. Thus the air exhaled from the lungs is utilized by man as an excitor. The exhaled air may issue from the lungs as it entered them, as mere breath, or it may be resisted in the larynx by the vocal cords which form the vibrator. The vocal cords work on the principle of a reed, and cause the exhaled air to be cut up into a series of minute puffs which constitute the note. Before this note reaches the outer air it must pass through the pharynx, whose main function is concerned with swallowing. It can then pass through the mouth, one vital function of which is chewing; or the nose, whose main function is associated with respiration and the sensation of smell. These cavities form the triple resonator of the voice. In speakers the tone may be non-existent, may have been impaired through mismanagement of the organs concerned, or may be merely latent. Few speakers utilize the tone of which they are capable, and some employ tone which resembles the sound of their remote ancestors. Others attempt to combine the vital and vocal functions of these cavities, and swallow at the same time as they declaim. Many chew their conversation, while others would seem to attempt the impossible task of smelling the tone as it issues from their noses!

So far no mention has been made of the movable nature of the mouth resonator. This can assume an infinite variety of shapes by reason of the variable position of the tongue and lips, singly or in combination. It is this variation in the shape of the mouth which has the effect of imprinting the character of the vowels on the tone.

QUALITY AND CHARACTER

In listening to a speaker we hear the tone of the voice, which is the result of the effect of the whole resonator upon the note produced. We also hear the character of the sound, due to the change in shape of the resonators. We might, therefore, say that we can recognise who is speaking by the quality, and what they are saying by the characters of the sounds. Clearly it is possible for the quality to be satisfactory and the character unsatisfactory. In other words the tone is good but the pronunciation is bad. In the same way it is possible for the pronunciation to be impeccable, but the tone indifferent. We shall see later that one of the main problems of voice production is to achieve maximum resonation, or tone, for each vowel, without sacrificing the clarity of its character.

CONSONANTS

The resonator possesses the additional function of impeding the free, open passage of the tone and in so doing forms the consonants of a language. Thus the three cavities may be thrown into communication with each other by bringing the lips together and lowering the soft palate, as in the case of M. The mouth may be eliminated as a resonator when the pharynx and nose only are used, as in the case of NG. The resonator may be completely closed and then suddenly opened, as in the case of B. The exit from the mouth may be narrowed in a great variety of ways by bringing the articulatory organs close together as, for example, in V.

Tone and word

The distinction between voice and speech should now be clearer. Voice is tone which is produced by a speaker in a manner exactly analogous to its manner of production in man-made instruments. The words of a printed page, on the other hand, may be regarded as a record of the movements of the speech organs, and correspond to the movement of the instrumentalist when he reads notes from the printed score. When the actor learns his words he is in reality committing to memory the sequence of movements for which the words are the visual symbols.

If this seems a surprising way of regarding the matter, the reader should speak this, or any other sentence which enters the mind, using the breath alone. Do not attempt to read it aloud, or to make the words carry, but speak the words on the breath. There must be no sound in the accepted sense of the word. What you have done could be heard quite easily a short distance away, for you have imprinted the vowel shapes and the articulatory movement on the breath as it issues from the lungs.

When these movements have been recorded they are recalled at the moment of performance. But in order that these movements should reach the members of the audience farthest away from the stage, the excitor, vibrator, and resonator are all brought into service in order to produce tone, on which the movements are superimposed and by means of which the movements are carried to the last rows of the theatre. Every time the actor speaks, this dual character of his instrument is made evident. It is at one and the same time a tone-producing instrument and a word-producing instrument. The human resonator, therefore, excels all others in its complexity and fascination, and yet the resonator, and in fact the whole instrument, behaves perfectly providing its natural functioning is not interfered with, and is developed on correct physiological principles.

BREATH, NOTE, TONE, WORD

This double action of the resonator must be continually borne in mind if the voice is to function correctly: in fact, it is safe to say that when the two functions are confused in training, success is rarely, if ever, achieved. There are, then, four aspects of utterance to be considered in training the voice; namely, the breath, the note, the tone, and the word. Each must be developed on its own merits, in the right order, and related to the rest during this process.

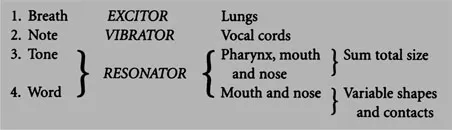

The foregoing may be summed up in tabular form thus—

The order of occurrence may now be grasped visually. The breath is seen to be the foundation upon which utterance is built. The first modification of the breath occurs when the vibrating vocal cords cut up the breath stream and in so doing form the note. The whole resonator then modifies the note and imparts tone. The shapes the resonator assumes, and the articulatory movements it makes, modify the tone. Speech, then, is the result of a whole chain of interrelated events. It is heard in perfection only when harmony exists between them, and only then will the instrument respond with subtlety and sensitivity to the intention of the actor.

SPEECH IN THE THEATRE

Speech in the theatre must be governed by the necessity of speaking to large numbers of listeners at one and the same time, so that every word carries convincingly; and yet it must be so controlled that the illusion of reality is not destroyed. Obviously, this is not true of most speech situations, where the demands on the voice are comparatively insignificant. But consider what is demanded of a Juliet in Act III or a Macbeth in Act V. Such roles can never be lightly undertaken, even by the most technically accomplished.

At the opposite extreme we may consider stage dialogue which is written with the express purpose of creating the illusion that what is spoken from the stage is not only true to life but is life itself. In this case the audience is in the position of a privileged spectator for whom the fourth wall of a room has bee...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half Title page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Note to the Fifth Edition

- Dedication

- Contents

- 1 The Voice in Theory

- 2 The Voice in Practice

- 3 The Tone

- 4 The Note

- 5 The Word

- 6 The Voice in Action

- 7 Conclusion

- Appendix

- Index