- 319 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Sex and Friendship in Baboons

About this book

Those who have been privileged to watch baboons long enough to know them as individuals and who have learned to interpret some of their more subtle interactions will attest that the rapid flow of baboon behavior can at times be overwhelming. In fact, some of the most sophisticated and influential observation methods for sampling vertebrate social behavior grew out of baboon studies, invented by scientists who were trying to cope with the intricacies of baboon behavior. Barbara Smuts' eloquent study of baboons reveals a new depth to their behavior and extends the theories needed to account for it.While adhering to the most scrupulous methodological strictures, the author maintains an open research strategy--respecting her subjects by approaching them with the open mind of an ethnographer and immersing herself in the complexities of baboon social life before formulating her research design, allowing her to detect and document a new level of subtlety in their behavior. At the Gilgil site, described in this book, she could stroll and sit within a few feet of her subjects. By maintaining such proximity she was able to watch and listen to intimate exchanges within the troop; she was able, in other words, to shift the baboons well along the continuum from ""subject"" to ""informant."" By doing so she has illuminated new networks of special relationships in baboons. This empirical contribution accompanies theoretical insights that not only help to explain many of the inconsistencies of previous studies but also provide the foundation for a whole new dimension in the study of primate behavior: analysis oft he dynamics of long-term, intimate relationships and their evolutionary significance.At every stage of research human observers have underestimated the baboon. These intelligent, curious, emotional, and long-lived creatures are capable of employing stratagems and forming relationships that are not easily detected by traditional research methods. In the process

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Sex and Friendship in Baboons by Barbara B. Smuts in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Zoology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 | INTRODUCTION |

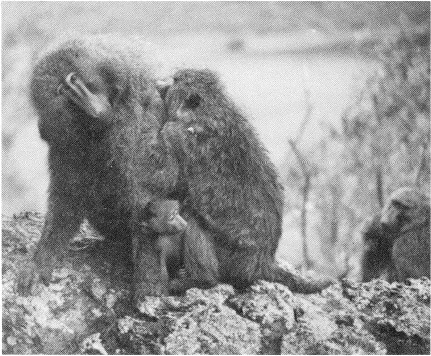

Pandora grooms Virgil on the sleeping cliffs at the end of the day. Pyrrha, Pandora’s daughter, peeks out at other baboons resting nearby. Friends often groom on the cliffs in the evening before going to sleep.

PROLOGUE

It was late afternoon, and the angled light brought into clear relief the sculptured planes of the baboons’ bony muzzles, highlighting the individuality of each face. In this light, I had no trouble recognizing Virgil and Pandora 100 m away, traveling slightly apart from the rest of the troop, wandering slowly toward me. Their steps were leisurely and their movements relaxed as they picked an occasional handful of young grass or dug for a bulb or root. By this time, the baboons had usually satisfied their voracious appetites, and when they sat they tended to lean back slightly as if to offset the weight of their full stomachs, which bulged above their feet, neatly placed close together. Virgil sat just this way, his chin pointed down and resting against his chest so that his expression, when he glanced up without moving his head, looked a little shy. But there was no hint of shyness in his face when he spotted Pandora, shuffling along behind him, apparently intent on finding a tasty bug or two under the small rocks she was turning over, one by one. He hunched his shoulders, pulled his chin in still further, flattened his ears against his skull, and made the skin around his eyes taut, showing the bright white patches of skin above each eyelid. At the same time, he alternately smacked his lips together rhythmically and grunted deeply with the slight wheeze that distinguished Virgil’s voice from those of the other adult males. Pandora, 5 m away, looked up and made a similar face back at Virgil and then, abandoning her rocks, headed toward him with the ungainly trot of a baboon anxious to get somewhere fast, but too lazy to run. As she approached, Virgil lip-smacked and grunted with increasing intensity, as if encouraging her to make haste. When she arrived, she plopped herself down on her back next to him and, dangling one foot in the air, presented her flank in an invitation for grooming. Virgil responded promptly, gently parting the sparse hairs on her belly with his hands, every now and then lightly touching her skin with his lips to remove a bit of dead skin or dirt from her fur.

But Virgil, like most male baboons, preferred being groomed to grooming, and after a few minutes he slowly sank to the ground, expelling his breath in a deep sigh. Pandora groomed him intently, working her way up his neck to the area around his eyes, carefully removing the grit that had accumulated there over the course of the day. After a few moments, they were joined by two of Pandora’s offspring, Plutarch, a juvenile male, and Pyrrha, an infant female. Pyrrha was in a rambunctious mood, and she used Virgil’s stomach as a trampoline, bouncing up and down with the voiceless chuckles of delight that accompany baboon play. Every now and then Virgil opened his half-shut eyes, peered at Pyrrha, and gently touching her with his index finger he grunted, as if to reassure her that he did not mind the rhythmic impact of her slight body against his full stomach.

After a while, Pandora stopped grooming, and Virgil moved away, slowly clambering up the cliff face where the troop would spend the night. He glanced back every few steps at Pandora and her family, who followed right behind. Finding a good spot halfway up the cliff, Virgil made himself comfortable. Sitting upright, he leaned backward against the rock face, and, grasping his toes in his hands, let his head sink to his chest—a typical baboon sleeping posture. Pandora sat next to him, leaning her body into his, one hand on his knee, her head against his shoulder. Her offspring squeezed in between Pandora and Virgil, and, in the dimming light, I could not tell where the body of one baboon began and the other left off. This is how they would remain for the rest of the night.

Virgil and Pandora were in late middle-age and had lived in Eburru Cliffs (EC) troop for at least 5 years. For the past year, while I had been spending my days with this troop, and probably for long before that, they had been close associates, feeding near one another during the day and sleeping together at night. Although Virgil and Pandora had probably mated in the past, their bond was not dependent on sexual activity. During my time with EC, at first Pandora was pregnant and later nursing her infant, so she was not sexually receptive during this period.

On the cliffs nearby was another pair, Thalia and Alexander. Thalia was an adolescent female who had not yet experienced her first pregnancy. At the moment, she was in the quiescent phase of her monthly sexual cycle, but in a few days the bare skin on her bottom would begin to swell, and for about 2 weeks she would exhibit the exuberant sexuality characteristic of adolescent female baboons. Alexander, also an adolescent, had a long, lanky body and an unusually relaxed disposition. He had transferred into EC troop just a few months earlier. Thalia, like the other females in the troop, was wary of this interloper and tended to avoid him during daily foraging. But as I watched the two of them sitting on the cliffs about 5 m apart, it was clear that, in Thalia, fear and interest were mixed in an uneasy balance.

Alexander was facing west, his sharp muzzle pointing toward the setting sun, watching the rest of the troop make their way up the cliffs. Thalia was grooming herself in a perfunctory manner, her attention elsewhere. Every few seconds she glanced out of the corner of her eye at Alexander without turning her head. Her glances became longer and longer and her grooming more and more desultory until she was staring for long moments at Alexander’s profile. Then, as Alexander shifted and turned his head toward Thalia, she snapped her head down and peered intently at her own foot. Alexander looked at her, then away. Thalia stole another glance in his direction, but when he again glanced her way, she resumed her involvement with her foot. For the next 15 minutes, this charade continued: Each time Alexander glanced at Thalia, she feigned indifference, but as soon as he looked away, her gaze was drawn back to his face. Then, without looking at her, Alexander began slowly to edge toward Thalia. Their glances at one another became more frequent, the intervals between them shorter, and their interest in other events less convincing. Finally, Alexander succeeded in catching Thalia’s eye as she was turning away. He made a “come-hither” face—the same face Virgil had made at Pandora—grunting as he did so (Figure 1.1). Thalia froze, and for a second she looked into Alexander’s eyes. Then, as he began to approach her, she stood, presented her rear to him, and, looking back over her shoulder, darted nervous glances at him. Alexander grasped her hips, lip-smacking wildly, and then presented his side for grooming. Thalia, still nervous, began to groom him. Soon she calmed down, and I found them still together on the cliffs the next morning.

This event represented a triumph for Alexander who, as a newcomer, had been trying for several weeks to establish a relationship with Thalia. As far as I knew, this was not only the first time a female had groomed him for more than a few seconds but also the first time he had spent an entire night close to one. From this moment on, he and Thalia spent more and more time together during the day, until they formed a consistent pair within the troop. Looking back on this event months later, I realized that it marked the beginning of Alexander’s integration into the troop.

STUDYING SEX AND FRIENDSHIP IN BABOONS

Soon after I began studying wild baboons in 1976, I realized that relationships like that between Virgil and Pandora or Alexander and Thalia were a central feature of baboon society. The idea of studying these long-term, cross-sex “friendships” provoked my interest for several reasons. Traditional studies of male–female relations in nonhuman primates had focused on male–male competition for mates and on brief bonds between males and sexually receptive females. In many of these studies, females were treated as relatively passive objects of competition who were of little interest once they conceived and were no longer sexually active.

Figure 1.1. (Top) Adult female with normal facial expression. (Bottom) Same female making the “come-hither” face.

Because female monkeys are normally either pregnant or lactating, however, periods of sexual activity constitute a very small proportion of their adult lives, and so the vast majority of interactions between males and females from the same troop are not explicitly sexual. Surely these “nonsexual” interactions—whatever they involve—must be crucial to understanding what goes on in the sexual arena. In particular, I suspected that a detailed knowledge of cross-sex relationships might provide important insights into the role females played in mate selection. Female choice of mates is considered an important force by evolutionary biologists (e.g., Darwin, 1871; Fisher, 1930; Bateman, 1948; Trivers, 1972), but, until recently, primatologists have paid it little attention.

Furthermore, a perspective that included female choice as well as male—male competition might help to explain several puzzling findings. If, as many primatologists had assumed, successful competition against other males was the primary determinant of male access to mates, then high-ranking males consistently should breed more often than lower-ranking ones. This, it turned out, was not always the case; numerous studies reported higher than expected frequencies of mating by lower-ranking, often older, males (DeVore, 1965; Saayman, 1971a; Hausfater, 1975; Packer, 1979b; Manzolillo, 1982; Strum, 1982). Another puzzling finding was the high degree of association between some adult males and particular infants, first documented by Ransom and Ransom (1971). What were these large, ruthless fighters doing in the “female domain,” looking slightly out of place as they cuddled and carried tiny infants? Models that focused on aggressive competition among males did not predict the existence of prolonged, affiliative relationships between either males and females or males and infants, yet such relationships clearly existed. I thought that a detailed study of cross-sex friendship might help to explain these findings and also contribute to a more complete understanding of baboon society.

This investigation of baboon friendship involved two major problems: one related to theory and the other to observation. My curiosity about issues like female choice and male–male competition reflects my interest in evolutionary theory, an interest shared by many of the scientists who spend their time watching animals. As intellectual descendants of Darwin, we are all concerned with the problem of ultimate or evolutionary causes of behavior. Has natural selection favored friendships among baboons? Specifically, does having a friend of the opposite sex help an individual to maximize his or her genetic contribution to future generations? These questions assume that male-female friendships are not simply historical accidents or idiosyncratic expressions of baboon psychology, but rather that they are products of evolution analogous to phenomena with more obvious adaptive value, such as maternal care or predator avoidance. This assumption, in turn, allows one to take full advantage of a series of powerful theories for explaining behavior developed by evolutionary biologists over the last 100 years.

This evolutionary perspective played a large role both in formulating my goals at the start of the study and in interpreting results during data analysis. The research itself, however, often took on a very different character due to the powerful influence of my subjects—the baboons. Many primate field workers compare their jobs to watching soap operas, except that the characters are real and they do not speak. This is an apt comparison because what captured my interest and motivated me to return to observe my subjects again and again was the daily drama of baboon life. As a result, all of the larger questions we begin with—for example, how do friendships contribute to individual reproductive success?—quickly become translated into a series of much more immediate, often compelling questions about phenomena of immediate concern to the baboon themselves. How does a friendship form? What makes it survive or, instead, falter in the early stages? Why does this male have half a dozen female friends, while that one has none? Even more basic, what exactly is friendship to a baboon? It was possible that the pairs I considered friends simply represented one end of a continuous distribution, with pairs who spent a lot of time together at one end and pairs who spent much less time together at another. However, it was my impression that interactions between friends differed not only in frequency but also in kind from interactions between other dyads, and that friends did indeed constitute a distinct category of relationships. The challenge was to reformulate this knowledge in a way that would permit both scientific scrutiny and objective communication to others without completely sacrificing the immediacy and vividness of the raw observations. Meeting this methodological challenge was a second major goal of the study.

The organization of this book reflects my two principal theoretical and methodological concerns. Research on any animal must begin with a general knowledge of the species’ distribution and social organization, and Chapter 2 provides this information. It also introduces the EC baboon troop and the females and males who were the focus of this study. Chapter 3 describes what it is like to watch baboons and how I structured my observations in order to address the problems and questions discussed above.

Chapter 4 defines baboon friendships and considers how individual attributes like age and status affected the number and types of friends that an individual had. Chapter 5 investigates the role played by each sex in maintaining friendship and the ways in which the interactions of friendly dyads differed from those of other pairs.

Chapters 6, 7, and 8 turn to evolutionary questions by considering how baboon social relationships might contribute to individual reproductive success. Chapter 6 analyzes the reproductive benefits of friendship from the female perspective, including male protection of female friends and affiliative relationships between males and infants. Chapter 7 investigates male–male competition for mates, and Chapter 8 considers the reproductive benefits of friendship from the male perspective. Through an analysis of the intimate connection between sex and friendship, Chapters 7 and 8 attempt to integrate information on male–male competition and female choice into a more unified model of male reproductive strategies.

Chapter 9 turns to some of the questions that to me are the most fascinating and frustrating ones raised by this study. Does the nature of friendship change through the life cycle? Are friendships disrupted by the female’s sexual interest in another male? What roles do courtship and possessive behaviors play in establishing and maintaining friendships? Do baboons feel emotions like jealousy, ambivalence, and grief toward their friends?

These are fascinating questions because they concern issues of great...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Chapter 1. Introduction

- Chapter 2. Baboons

- Chapter 3. Field Work and Data Analysis

- Chapter 4. Defining Friendship

- Chapter 5. What Made Friends Special

- Chapter 6. Benefits of Friendship to the Female

- Chapter 7. Male–Male Competition for Mates

- Chapter 8. Benefits of Friendship to the Male

- Chapter 9. Making, Keeping, and Losing Friends

- Chapter 10. Comparative Perspectives

- Appendixes I–XIV

- Bibliography

- Subject Index