![]()

Part One

Setting the Scene

![]()

Chapter 1

The Larger Picture

As many commentators on civil society have written, it makes a lot of sense to think of the political economy of the modern society in three basic sectors – the state, business and a third sector defined by citizen self-organization. The states distinctive competence is the legitimate use of coercion; the business sectors competence is market exchange; and the third sector’s competence is private choice for the public good. Citizens mobilize through values that they share with other citizens and through shared commitment to action with other citizens.

Civil society is the dynamic equilibrium relationship among these three actors. As Salamon and Anheier (1999) have put it:

[A] true ‘civil society’ is not one where one or the other of these sectors is in the ascendance, but rather one in which there are three more or less distinct sectors – government, business and nonprofit – that nevertheless find ways to work together in responding to public needs. So conceived, the term ‘civil society’ would not apply to a particular sector, but to a relationship among the sectors, one in which a high level of cooperation and mutual support prevailed.

The citizen sector becomes operational through citizens organizing themselves for action for the common good. Formal organizations that result will be stronger if they address social problems together with government and business – and the most effective civil society organizations will be those that have a strong base in many different kinds of citizens in their country.

This handbook sets out to do two things – to change the way that civil society organizations think about their own scope and potential; and to provide tools that civil society organizations can use in mobilizing (mostly) domestic resources. The book is also interested in foreign resources that build self-reliance and sustainability. This challenges the prevailing orthodoxy of the aid system, which creates more and more dependency on foreign resources, and retards the development of an indigenous citizen resource base.

This handbook is based on the following beliefs:

- The existing pattern of support for civil society organizations in the South, which is largely based on foreign funding, is neither desirable nor sustainable.

- A variety of domestic resources are potentially available to Southern civil society organizations, but have not been adequately researched, attempted, or mainstreamed by them.

- Local or domestic support, expressed through local funding, is fundamentally important for the long-term sustainability of civil society organizations and their programmes.

For these reasons it is important for Southern civil society organizations to learn more about the different strategies for resource mobilization that are available to them.

This handbook will introduce you to 12 different approaches for resource mobilization, each of which will have its own rationale, and each of which will have its own advantages and disadvantages. Using these different approaches will not only change where your money is coming from, but may also change the way that your CSO thinks of itself and operates. The advantages and disadvantages may appeal to your organization in different ways.

THE NEED FOR RESOURCES

Civil society organizations need resources so that they can be effective and sustainable. As organizations look for strategies to mobilize resources, they should be guided by these two important principles, and assess the various possible alternatives from these two standpoints.

The place to start with any CSO or group of CSOs is where they are at present. To set the scene for new ideas in resource mobilization, each CSO should look at, and list, its present resources. Then, for each one, it should give its origin, advantages and disadvantages from the point of view of effectiveness and sustainability. The result of this exercise is likely to show the CSO that it is relying on a very restricted number of resources. For many development CSOs, the exercise reveals a heavy reliance on grants from Northern donors, and that many of the grants have disadvantages of different kinds from the perspective of effectiveness and sustainability. The main advantage of such grants, on the other hand, is that they are available, that such funds are indeed offered, and that they are usable by the CSO community. Because they exist, such grants have become the norm. Other forms of resource mobilization seem strange. Because they are unfamiliar it is assumed they are difficult.

The other result of this exercise, particularly when practised with a large group of different CSOs, is that it will throw up a number of different experiences beyond grants from Northern donors. These experiences will probably be of less importance financially than the foreign grants, but will allow participants to appreciate the range of other possibilities that exist, and allow interorganizational learning based on actual experience.

Resources, particularly money, are not value neutral or value free. They bring certain baggage with them, depending on their origin and culture. Some CSOs will have strong reactions to some kinds of resources (like, for instance, resources from the corporate community), but will accept the possibility of resources from individuals. Other CSOs will start from different perspectives. The important point at present is to be open to a range of possibilities and to suspend critical judgement until you have understood them better.

The CSO world is very likely to change. Some of these changes are already taking place, particularly the drying up of funds from Northern NGOs. Existing patterns of resources to Southern CSOs will likely fall into one or more of the following categories:

- They will not be available to your organization in the future.

- They have significant disadvantages that outweigh their advantages.

- They seem less attractive in relation to some other resources.

THE CHARACTERISTICS OF CSOs

This handbook is based on the premise that there is a continuing need for effective, ethical, committed and sustained CSOs, whose main purpose is to improve the situation of the poorest and most disadvantaged people in the South. It is taken as a given that CSOs can do things which neither of the other national development actors – the government and the corporate sector – can do on their own. If this premise is accepted, it is obvious that CSOs need resources to allow them to have an impact on their chosen field of work, and to sustain them so that they can continue to have such an impact. The question is which resources and how they can be acquired.

While most CSOs indeed have as their purpose the improvement in the lives of the poorest and most disadvantaged, there are increasing numbers of ‘pretender’ organizations who call themselves by the name of CSOs, but whose purpose is different. Such organizations are created for personal income or private interests, or as a front for governments or businesses. Precisely because such pretenders are challenging the CSO world, and because such ‘bad apples’ can spoil the reputation of the citizen sector as a whole, it is valuable to reiterate the most important characteristics of civil society organizations before we look at what such CSOs need, and how such needs can be met.

Civil society organizations created in the public interest, both North and South:

- are driven by values that reflect a desire to improve lives;

- contain elements of voluntarism (ie are formed by choice, not by compulsion, and involve voluntary contributions of time and money);

- have private and independent governance;

- are not for anyone’s profit (ie they do not distribute profit to staff or shareholders);

- have a clearly stated and definable public purpose to which they hold themselves to be accountable;

- are formally constituted in law or have an accepted identity in the culture and tradition of the country.

WHAT DO CSOs NEED?

What do such organizations need in order to be effective and sustainable? There are five basic requirements:

1 Good programmes that actually do improve lives and can be shown to do so, as opposed to programmes that claim to do so, but which actually have not had the impact desired.

2 Good management which will make sure that any resources are efficiently put to the service of the good programmes. Good management also means a proactive practice of performance accountability, including rigorous public reporting.

3 A commitment to sustainability: CSOs need to appreciate that their mission is unlikely to be achieved quickly and that they need to be involved over the long haul. CSOs need to be marathon runners rather than sprinters.

4 The financial resources to support the good programmes, the good management and the sustainability mentioned above.

5 Local support, which includes:

6 a supportive political, legal and fiscal environment in which they are enabled to exist and flourish;

- good human resources to work for the NGO;

- a good reputation built on the credibility they have acquired from their good programmes;

- supporters from a variety of different sources (local development agencies, national governments, specific groupings in society, the general public);

- and, specifically, well-placed champions who can defend them when they are under attack, and promote them when they have something of wide significance to offer.

THE PRESENT PATTERN OF CSO RESOURCES

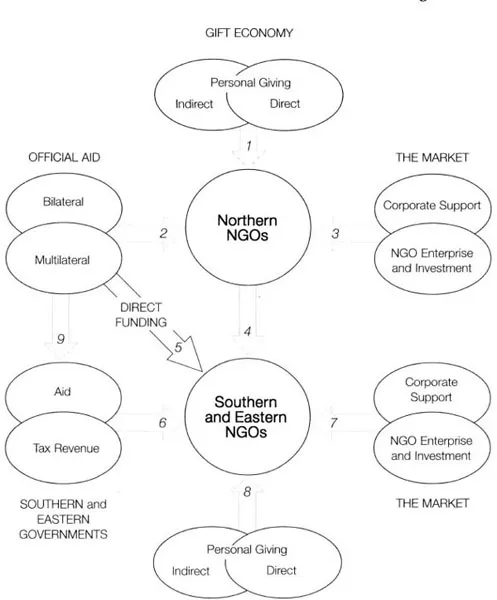

Before we look at the different ways of mobilizing resources that may or may not suit your organizations circumstances, it is useful to get an overview of the ways that resources come to CSOs in the world. Figure 1.1 illustrates how both Northern and Southern CSOs receive their funding.

Source: Alan Fowler (1997) Striking a Balance, Earthscan Publications, London

Note: Use of NGO not CSO

Figure 1.1 Striking a Balance

In the South, CSOs can expect the possibility of resources from the following:

1 Northern governments

• Directly as bilateral assistance (Channel 5).

• Indirectly as multilateral assistance (Channel 5).

• Via Northern CSOs (Channel 4).

• Via their own governments as bilateral assistance relayed to CSOs (Channel 6).

2 Northern CSOs directly (Channel 4).

3 The market

• From businesses (Channel 7).

• From CSO s enterprises, including investments (Channel 7).

4 Citizens

• Directly as gifts (Channel 8).

• Indirectly as support (Channel 8).

5 Their own governments directly, national and local (Channel 6).

Research done by the Johns Hopkins Institute for Policy Studies in a number of countries in the North suggests that the greatest flow of resources for Northern CSOs comes from government, followed by the market, followed by the gift economy. This reflects the pattern of government contracting of CSOs to supplement their work for them, and the large number of Northern CSOs (particularly foundations) that have large investments.

The same Institute for Policy Studies has done some research in a limited number of Southern countries. It is clear that the largest amount of resources available for CSOs is from Northern CSOs, and increasingly from Northern governments directly. All the other sources of support, however, are potentially available to CSOs, even if, at the present, they have not availed themselves of them. It is useful to think how CSOs could construct their own unique mixture of government, market and citizen support to help their work. Think of the resources that come into your own organization, or an organization that you know, in the terms described above, and think of these both in terms of financial and non-financial resources.

THE EXISTING PATTERN OF RESOURCES FOR CSOs

At present it is likely that the subset of CSOs oriented towards development work are ...