![]()

Part I

Background

![]()

1

Introduction

Riki Thérivel and Maria Rosário Partidári

The practical application of strategic environmental assessment (SEA) – the environmental assessment of policies, plans and programmes – has grown by leaps and bounds in the last few years. Whilst very few countries have formal SEA regulations, some have issued guidance on how SEAs should be carried out. Ad hoc SEAs have been carried out in a large number of countries. New SEA regulations and guidelines are being proposed worldwide, including a European SEA directive and national SEA legislations in many European countries. In Australia a major review process of the environmental impact assessment system is under way, including the specific consideration of SEA.

This book shows how SEA has been implemented in practice in the last few years. It aims to give ideas and inspiration to those who are commissioning, carrying out, reviewing, and teaching about SEA. It also aims to promote best practice in SEA. Almost every SEA we have looked at shows elements of good or best practice, but no SEA has included all of these elements. The analyses and case studies presented here should give valuable ideas for how other, future SEAs can be effectively carried out.

Chapters 1 to 3 set the context for the remaining case study chapters. Chapter 2 reviews SEA regulations and guidance worldwide. Chapter 3 discusses SEA models and methodologies. Chapter 4 to 13 are case study chapters. The case studies were collected from countries that have considerable experience with SEA, or where particularly good examples were known to exist. They are organised in three sections: sectoral SEAs, SEAs of land-use plans, and policy SEA. The case studies exemplify different scales, different countries, and different approaches to SEA. The final chapter briefly discusses some issues identified in the case-studies as being constraints to an effective SEA process, as well as positive learning points on how SEA can contribute to the increased effectiveness of environmental assessment.

This chapter reviews what SEA is, who uses it, why it is needed and what some of its limitations are. It then discusses how SEA fits into the decision-making process for policies, plans and programmes, and considers the structure of the case study chapters in more detail.

Definitions

The simple definition of SEA is that it is the environmental assessment (EA) of a strategic action: a policy, plan or programme (PPP). In this sense, SEA should be seen as an EA tool, on a par with other EA tools such as project EIA, cumulative impact assessment and auditing. More specifically, SEA is:

the formalised, systematic and comprehensive process of evaluating the environmental effects of a policy, plan or programme and its alternatives, including the preparation of a written report on the findings of that evaluation, and using the findings in publicly accountable decision-making (Thérivel et al, 1992).

SEAs therefore differ from:

• environmental impact assessments (EIAs; the term is used in this book only in relation to projects) of large-scale projects because these are site-specific and normally involve only one activity, and are therefore not strategic;

• ‘integrated’ PPP-making, which incorporates environmental issues in the PPP-making process but does not involve the stages of a formal EA process, particularly an appraisal of alternatives based on environmental objectives and criteria;

• environmental audits or ‘state of the environment’ reports, which do not predict the future environmental impacts resulting from the application of a PPP;

• SEA studies, which do not influence decision making;

• many ‘environmental appraisals’, environmental strategies or cost-benefit analyses: those which do not predict the likely future effects of a PPP, do not consider a range of environmental components, and/or do not result in a written report; and

• various integrated management plans which deal with environmental impacts on a specific biotope (eg coast, heathland) but do not specifically inform decision making on alternative planning and development options that could result in sounder environmental outcomes.

SEA is only one of various terms used to refer to EA at the strategic level. Others include policy EA, policy impact assessment, sectoral EAs, programmatic environmental impact statement, EA of PPPs and integration of EA into policy-making. The word ‘strategic’ in SEA has diverse meanings in the sequence of decisions, from broad policy visions to quite specific programmes of more con-crete activities. The function of SEA, and the terminology associated with that function, are still subject to extensive debate. Each country, political or economic system will need to adopt the process and terminology most suitable to that context, in a way that is practical and responsive to integrative approaches towards sustainability goals. It is not the intention of this book to discuss the value of different forms, or definitions, of SEA. The book simply assumes that SEA addresses the strategic component in decision instruments at the policy, planning or programmatic level. The strategic component refers to the set of objectives, principles and policies that give shape to the vision and development intentions incorporated in a PPP. SEA deals with concepts, and not with particular activities in terms of their location or technical design (Partidário, 1994).

The difference between policies, plans andprogrammes in practice is not very clear. Wood and Djeddour (1992) suggest that:

A policy may …be considered as the inspiration and guidance for action, a plan as a set of co-ordinated and timed objectives for the implementation of the policy, and a programme as a set of projects in a particular area.

However, in practice this sequence can vary: for instance, in the UK, national level planning policy guidance affects local authority development plans, which in turn are composed of policies and individual site proposals. In Canada, poli-cies directly affect the shaping of programmes, and subsequently individual projects. In Portugal’s regional development programmes, programmes of poli-cies provide the context for the development of plans and individual projects at the same level. What is important is that one policy, plan or programme often sets the structure for another PPP, which in turn may influence projects, and thus there is a hierarchy or tiering of PPPs. This book mostly uses the generic term ‘PPP’. However, where a distinction between tiers needs to be made, it follows the sequence:

policy ⇒ plan ⇒ programme ⇒ project

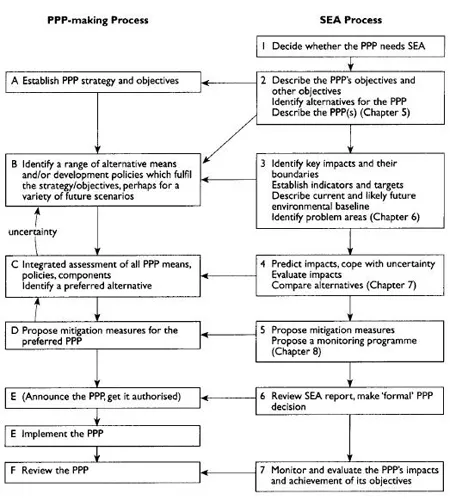

As PPPs are tiered, so can SEAs be, with higher-level SEAs setting the context for lower-level SEAs, which in turn set the context for project EIAs. Figure 1.1 shows the broad stages of the PPP and SEA processes.

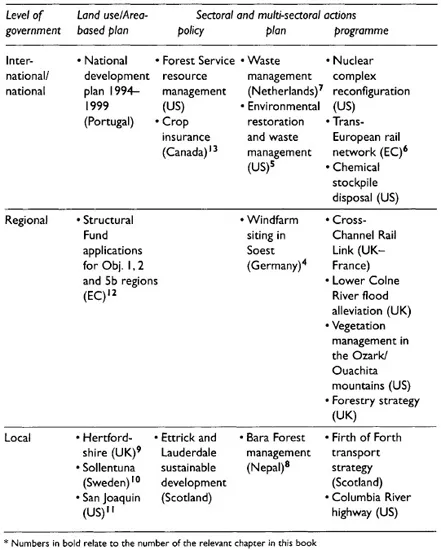

SEA can be applied to three main types of actions: sectoral PPPs, which are related to specific sectors (eg mineral extraction, energy, tourism); areabased or comprehensive PPPs, which cover all activities in a given area (eg land-use or development plans); and actions that do not give rise to projects but nevertheless have a significant environmental impact (eg agricultural practices, new technologies, privatisation). Table 1.1 gives examples of PPPs for which SEAs have been carried out to date.

Figure 1.1 Stages in, and Links Between, PPP-making and SEA

Interest Groups in SEA

Four main interest groups are involved in SEA: the action-leading agent (proponent), the competent authority, the environmental authority and the public.

The action-leading agent is the organisation responsible for developing the PPP. This could be a private company, such as an electricity generating company or the proponent of a new technology; a public sector agency such as the ministry for energy, or a local authority; or a consortium of private and/or public sector organisations, such as a group of housing developers or a regional council composed of several local authorities.

Table 1.1 Examples of Tiers of SEAs

The competent authority – usually a government or quasi-government organisation – is responsible for deciding on the PPP. The action-leading agent and the competent authority are usually the same, public, organisation: for instance a transport ministry could propose a road policy and programme, prepare the SEA and decide whether the programme should go ahead. This has the disad-vantage of potential vested interests and bias, especially where the PPP proponent carries out the SEA and decides whether the PPP should be approved (the ‘poacher-gamekeeper syndrome’). However, it has the advantage of allowing the PPP to be more easily refined based on the findings of the SEA.

The environmental authorit(y)ies contribute information to, and are consulted as part of, the SEA process. They could include the relevant environment agency, local wildlife groups, and pollution regulatory organisations.

Few SEAs have made a concerted effort to seek and address public opinions, for reasons of confidentiality, because the PPP may be considered too sensitive for public debate prior to approval or because of the sheer complexity of con-sulting the public on a national or region-wide issue. Often the general public does not comment on strategic decisions even where its input is actively sought. As such, the public is often represented by various pressure groups and elected representatives.

Need for SEA

The reasons SEA is needed generally divide into two groups: SEA counteracts some of the limitations of project EIA, and it promotes sustainable development.

Counteracting the Limitations of Project EIA

Although project EIA is becoming widely used and accepted as a useful tool in decision-making, it largely reacts to development proposals rather than proactively anticipating them. Because EIAs take place once many strategic decisions have already been made, they often address only a limited range of alternatives and mitigation measures; those of a wider nature are generally poorly integrated into project planning. Consultation in EIA is limited, and the contribution of EIA to the eventual decision regarding the project is not clear (CEC, 1993; DoE, 1991; Glasson et al, 1995; Lee and Brown, 1992; Thérivel et al, 1992).

Project EIAs are also generally limited to the project’s direct impacts. This approach ignores such impacts as:

• the additive effects of many small projects or management schemes that do not require EIA, for instance, agricultural management schemes or defence projects;

• induced impacts...