1

Statement of Themes

‘Tis laughable that man should fondle such surprise

at animal behaviour, seeing some beetle or fly

- whose very existence is so negligible and brief -

act more intelligently than he might himself

had he been there to advise with all his pros and cons,

his cause, effect and means: Such conduct he wil style

‘Marvels of Instinct’, but what sort of wisdom is this

that mistaketh the exception for the general rule

and the rule for the exception ?

ROBERT BRIDGES

1.1 Natural History

A much-esteemed experimental psychologist once published a denunciation of the excessive use of tame rats in laboratory studies of behaviour. His article, inspired by a work of Lewis Carroll, was entitled ‘The Snark was a Boojum’; it claimed that comparative psychology had softly and suddenly vanished away under predation by Rattus norvegicus var. albinus [38].

1. Rattus norvegicus. An adult male on the run.

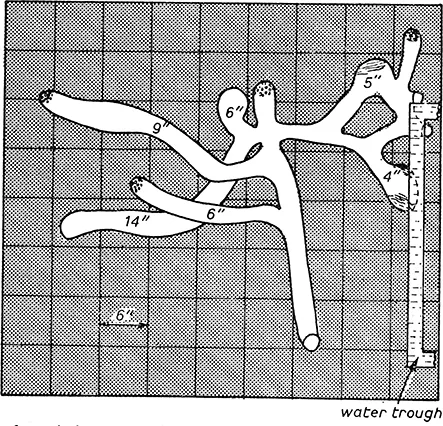

It is true that comparative ethology cannot exist without information on the behaviour of many species; but it is still possible to illustrate many of the principles of ethology from one genus, or even one species, only. Accordingly, the species with which this book is mainly concerned is Rattus norvegicus Berkenhout, the common ‘brown’ rat of Europe, North America and elsewhere. It is sometimes called the ‘Norway rat’. Albino and other tame varieties of this species have been used in laboratories for more than half a century. Another species which will be mentioned is Rattus rattus L. This, variously called the black, house, roof, ship or alexandrine rat, is less common in Europe and North America. It varies greatly in colour. Individuals of both species can be tamed, if they are regularly handled from an early age [26]; but there are no laboratory strains of R. rattus. R. norvegicus is a burrowing animal (figure 2) but it can climb well; rattus does not burrow, but climbs even better and typically nests above ground.

2. System of earth burrows of Rattus norvegicus. Figures show depths. (After Pisano & Storer [244].)

Both species have a long history of association with man, well described by Barrett-Hamilton & Hinton [34]. It is possible that living in human communities, and competing with man for food, have led, by a process of natural selection, to genetical changes influencing behaviour; this applies especially to the extreme fear or avoidance of unfamiliar objects (such as traps) displayed by wild norvegicus. The omnivory which rats display may, however, have evolved before human communities become prosperous enough to support populations of small rodents.

Most studies of rat behaviour have been on tame varieties of norvegicus. These laboratory rats can easily be crossed with wild ones, but their behaviour differs from that of wild rats in many important respects, not all of them obvious. They have been selected for tameness, that is for a reduced tendency to flee from man or to fight when handled. In addition, strange objects which would induce ‘fear’ in wild rats provoke only ‘curiosity’ in tame ones; and tame males do not fight other males with anything like the same intensity as wild males. Their selection of foods, when faced with a choice, may also differ from that of wild rats. A similarity of behaviour, which they are rarely allowed to display, is that they burrow readily.

Differences in behaviour have been paralleled by changes in growth, many of which have been described in a standard work by Donaldson [87]. There are also important differences in the relative weights of organs, such as the adrenal glands. A population of wild rats is of course genetically heterogeneous, and it will be shown later that generalizations about the behaviour of wild rats often have to be qualified by reference to individual variation. In an inbred strain of tame rats genetical variation is greatly reduced. This has the advantage, for certain kinds of experiment, that differences between experimental and control groups are more likely to be the effects of the experimental procedure, and less likely to be due to genotypic variation with which the experimenter is usually not concerned. Nevertheless, it is misleading to speak of ‘the laboratory rat’ in a way which might imply that laboratory rats are quite uniform. First, some genetical variation always remains. Second, in inbred strains, minor differences of environment can produce marked phenotypic variation: in this respect, highly inbred animals may be less convenient material for experiments than the firstgeneration hybrids between inbred strains; such hybrids are both genetically and phenotypically often remarkably uniform. Their use may make possible a reduction in the number of experimental animals needed to give conclusive results [214]. Third, and above all, there are several varieties of tame rats in common use: in addition to the familiar albinos, which have pink eyes and poor eyesight, there are coloured types – hooded, piebald, grey and black – which have a pigmented iris and correspondingly better vision [140].

The existence of a number of tame strains of a species which is also easily available in the wild form makes Rattus norvegicus a particularly convenient animal in which to study behaviour. This convenience has its dangers: a concentration of research on one species could lead to the production of an absurdly incomplete and distorted picture of animal, or at least of mammalian, behaviour. Accordingly, in this book, mention is made of other species wherever it seems important to emphasize resemblances to rats or differences from them; or when some aspect of behaviour has been insufficiently studied in rats. However, of all mammals, rats are those which, with present knowledge, can best be used to illustrate the principles of the study of behaviour. The rest of this chapter introduces the main definitions, and general concepts, of which use has to be made in such a study.

1.2 The Definition of Behaviour

By behaviour is meant here the whole of the activities of an animal’s effector organs: in the case of a mammal and most other sorts of animal, these are its muscles and glands. This definition includes the contraction of smooth muscle and the secretions of all glands, and is intended to do so. Nevertheless, most of this book is concerned with behaviour in a rather narrower sense, namely, the movements of the whole animal – movements which depend on the activity of many skeletal muscles. This does not necessarily exclude facts which are commonly thought of as coming within the realm of physiology. One way of studying gross, overt behaviour is to seek the internal processes which influence it, especially those in the sense organs and the nervous system; but this in turn demands enquiry into such things as the effects of hormones, the level of sugar in the blood and so on. Further, the study of the senses should not be confined to those that convey information about the world outside the animal (the exteroceptors), but should also comprehend the internal sense organs: of these, the proprioceptors, which are present in the organs in which most movement occurs (the muscles, tendons and joints), play an essential part in every act of behaviour.

The scientific study of behaviour (ethology) is therefore not marked off sharply from physiology, of which indeed it could be regarded as a branch. Nevertheless, ethology has methods of its own, different enough from those used in laboratories, or described in texts, of physiology for it to deserve a separate name. This is partly because a physiologist is usually concerned with units of activity smaller than those studied by ethologists: research on changes in salivation rates due to stimulation of the chorda tympani nerve would usually be done by a physiologist; but an inquiry into salivation in response to the smell of food would be more likely to be done in a department of zoology or psychology. In the second case the experimenter is observing the operations of a unit which includes the olfactory organs and parts of the brain, as well as the motor nerve fibres which supply the salivary glands and the glands themselves.

The difference in size of unit exists also, as already implied, in the responses studied. A pattern of muscular contraction, as in a tendon reflex, is the type of ‘molecular’ response which is within the domain of physiology. ‘Molar’ responses, involving much more complex relationships, belong to the study of behaviour as it is usually practised. These larger responses bring about either a change in the environment (for example by moving some object, or dissolving it in a glandular secretion), or they alter the relation of the animal to its environment (for example, by moving the animal off to another place).

Whatever form is taken by the activity studied, the behaviour is always a combined result of the actions of many organs. In elementary texts this fact is sometimes represented by a diagram of a ‘reflex arc’, in which a single receptor (such as a sensory organ in the skin) is shown connected to a single afferent nerve fibre, and this in turn to a single connecting neuron in the central nervous system; the arc is completed by one motor neuron ending on one muscle fibre or gland cell. This is useful in so far as it conveys that overt behaviour is a result of processes in the organs symbolized in the diagram. But even a ‘simple’ reflex is a result of a complex interaction of units in the central nervous system: there is no one-to-one relation between sensory, connecting and motor nerve cells; and several muscles are involved, some contracting, others relaxing, all in an orderly way. Further, some neural processes are inhibitory: they are not, as many diagrams imply, all excitatory. In a simple reflex there is progressive relaxation of the muscles antagonistic to the contracting ones; and this depends on inhibition in the central nervous system. A ‘simple’ reflex as a whole is a highly integrated performance depending on the smooth functioning of large numbers of nerve cells.

More complex activities involve correspondingly greater elaboration in the central nervous system. This applies to most many-celled animals, but above all to the mammals, in which a vast mass of connecting neurons is interposed between receptors and effectors. This mass of nerve tissue does not function in the machine-like way suggested by the reflex arc diagram, and not very much is known of how it does work. Nevertheless, despite our ignorance of brain function, it is still helpful to speak in terms of the control of behaviour by the nervous system, since otherwise we are tempted to talk as though animals were controlled by a set of gremlins—urges, drives, instincts and so on – and this does not help us to understand behaviour as it actually is. At the same time, we have to use words which refer to the different kinds of overt behaviour – the activities that we can observe without regard to internal processes. It is to these activities that we must now turn.

1.3 ‘Learning’ and ‘Instinct’

When an animal performs some action, it is often said to have done so in response to a stimulus. The term stimulus may be formally defined as any event which causes a change in an animal’s receptor organs and, as a result, in its nervous system. This definition is very general, and lacking in precision since it leaves open the meaning of ‘receptor organ’; but in practice it is convenient, and it does not encourage ambiguity. Sense organs may be looked on as instruments which measure either the intensity or the amount of some form of energy falling on them. To make sense, any statement concerning stimuli must specify (or imply) what kind of energy (light, pressure and so on) is involved. The definition of ‘stimulus’ excludes changes in the surroundings to which the animal’s sense organs cannot respond: for instance, a change of colour in an object cannot by itself influence a rat’s behaviour, because rats have no colour sense.

The sense organs and the nervous system are so arranged that the impact of a very small charge of energy can release a much larger amount of the energy stored in the animal’s muscles. If a rat is sitting still, and a short, high-pitched sound is made near it, the energy of the sound waves falling on its eardrums is trivial; yet the animal may leap to its feet and run to cover.

The nervous system not only has this amplifying effect: it also determines the pattern of the response. The rat disturbed by a sound runs by a direct and economical route to cover, provided that it has already had the opportunity to move about the area on previous occasions. But if it is in a strange place, although it will run wildly about, its movements will not be related to the whereabouts of shelter. This is an example of the kind of change that often takes place in an animal when it repeatedly encounters the same circumstances; we know of this change through altered behaviour. The central nervous system is the organ which, by very complex means, makes this alteration possible.

An important feature of such changes of behaviour is that they are adaptive: that is, they tend to make more probable the survival of the individual or the species. On the one hand the rat running to cover may escape a predator. On the other, a female may respond to the squeaking of her young by returning to her nest and allowing them to feed; this may not affect her own chance of survival, but it increases that of the young rats and so, in general, of the species. In both examples the animal has learnt the route to be followed.

Altered behaviour of this sort is an example of individual or ‘physiological’ adaptation. It must be distinguished from genetical, or evolutionary, adaptation, in which the genotypic make-up of a population is changed. Physiological adaptation occurs in all animals. An organ which is subject to much use, instead of wearing out like part of a machine, often enlarges or becomes more efficient in some other way. The type of physiological adaptation that goes on in the central nervous system is exceedingly complex: it is sometimes called ‘learning’. Learning in this sense has been defined as internal processes which manifest themselves as adaptive change in an individual as a result of experience [311]. However, the variety of learned behaviour is very great, and it may be doubted whether convenience is best served by grouping all the underlying processes under one term.

Another, still more dubious grouping is that which divides complex behaviour into two kinds, the innate (inborn or, sometimes, instinctive) and the learned (which includes ‘intelligent’). This distinction must now be examined.

In the behaviour of any species there are certain patterns of movement which are readily recognized as ‘the same’ when performed by any individual. (Some are confined to one sex.) For instance, the behaviour of a male rat approaching and copulating with a female in oestrus consists of a fixed sequence of actions. The same applies to the behaviour of the female in oestrus when approached by a male. A pattern is a repeated set of relationships, and this is found in these examples. These activities are sometimes called fixed action patterns; in this book, when they have to be referred to in general, they will be called stereotyped behaviour. They are, to repeat, typical of the species (or other taxonomic group) to which the animal belongs and so are often said to be speciescharacteristic.

A fixed action pattern is often evoked with a high degree of predictability by a specific stimulus. Such releasing stimuli have been studied in great detail in some species of birds and fish, but not so fully in mammals. In the case of the male rat and the female in oestrus, the mating behaviour of the male is evidently released, in the most usual situation, by the combination of a characteristic odour with the visual pattern made up of the shape and movements of the female; once the female has been mounted there are also tactile effects. The fact that a highly specific pattern of behaviour (that is, of movements) is released by an equally specific stimulus pattern (however complicated), gives a machine-like impression to the observer: one is tempted to speak, by analogy, in terms of such things as triggers which, when pressed, produce automatically a predetermined system of movements. The internal ‘mechanism’ involved is obviously the whole organization of sense organs, nervous system and muscles, but there is evidently a special arrangement in the central nervous system which determines the precise pattern of actions involved.

So far, then, we can say that the behaviour of an animal in response to a particular stimulus or situation may obviously have been modified, in which case we say it is a product of learning; or it may be stereotyped, in which case we often do not know to what extent learning has played a part in its development. Whatever the degree to which behaviour is stereotyped, we can usually see that it is related to the biological needs of the animal: it has ‘survival value’. The relationship of behaviour to need must now be examined further.

Fixed action patterns sometimes come as the end of longer sequences of activities. A rat feeds after it has moved fro...