- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book explores the author's wide-ranging work on muscle research, which spans more than 50 years. It delves into the dogmas of muscle contraction: how the models were constructed and what was overlooked during the process, including their resulting shortcomings. The text stimulates general readers' and researchers' interest, highlights the author's pioneering work on the electron microscopic recording of myosin head power and recovery strokes, and presents a frank discussion on how the original work sometimes tends to be overlooked by competing scientists, who hinder the progress of science.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mysteries in Muscle Contraction by Haruo Sugi in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Anatomy. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Historical Background

A most prominent characteristic of animals is their ability to move by muscle contraction. The mechanism of contraction has therefore attracted investigators’ interest over many years. Although it has been known since the 19th century that the skeletal muscle, which produces the movement of the animal body, is cross-striated and is called striated muscle, the functional meaning of the striation has remained a mystery over many years. Even in the early half of the 1900s, no investigators were aware of the functional significance of cross-striations in the skeletal muscle.

At that time, it was generally believed that the muscle was composed of numerous contractile molecular chains extending along the entire muscle length; in the resting muscle, the molecular chain is in the extended state, and in the contracting muscle, folding of the molecular chain takes place and results in shortening and force generation in the muscle (Buchthal and Kaiser, 1951). This hypothesis was called the transmutation theory and could explain almost all mechanical properties of the resting and the contracting muscle. The transmutation theory was proved wrong, and this tells us that the ability of a theory to explain many known phenomena does not necessarily mean that it is correct.

1.1 Structural Organization of Striated Muscle

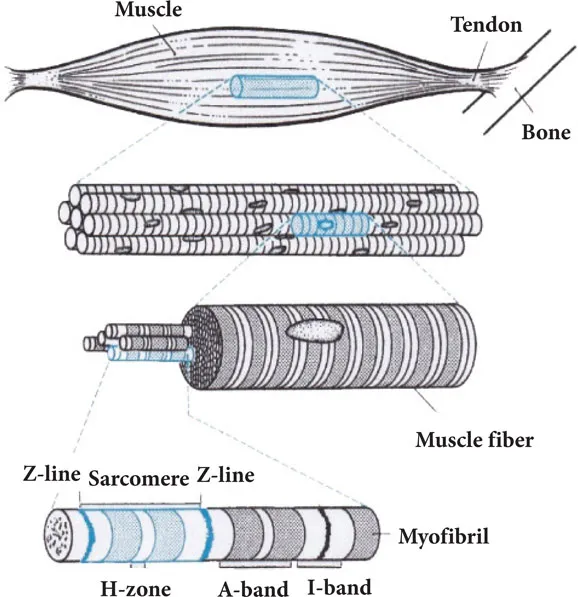

Figure 1 illustrates the structural organization of the vertebrate skeletal muscle. A skeletal muscle is firmly connected to the bone at both tendinous ends and is composed of long and parallel muscle fibers (diameter, 50–100 µm), which are multinucleate giant single cells. A muscle fiber is composed of a number of myofibrils (diameter, ~1 µm). Cross-striations are clearly visible in both muscle fibers and myofibrils.

Figure 1 Structural organization of vertebrate skeletal muscle. A muscle consists of muscle fibers, which contain myofibrils. The striation pattern is composed of A- and I-bands, Z-line and H-zone.

In the early 1940s, Szent-Györgyi and coworkers found that the muscle contains two different contractile proteins—actin and myosin—and showed ATP-induced shortening of actomyosin thread, i.e., mixture of actin and myosin, suggesting that muscle contraction results from the interaction between actin and myosin, coupled with ATP hydrolysis (Szent-Györgyi, 1951). These findings were followed by the monumental discovery of the sliding filament mechanism.

1.2 Discovery of the Sliding Filament Mechanism

H. E. Huxley started his research career by studying the X-ray diffraction pattern from the frog skeletal muscle and found a hexagonal double array of filaments (H. E. Huxley, 1953a). When he visited my laboratory in 1978, he told me the following story about his monumental discovery of the sliding filament mechanism.

When he found the hexagonal myofilament lattice in the muscle, Professor Dorothy Hodgkin asked him to visualize his finding. Then he studied the muscle structure electron microscopically and found that the two contractile proteins, actin and myosin, exist in the muscle in the form of two different myofilaments and constitute overlapping double filament arrays (Huxley, 1953b).

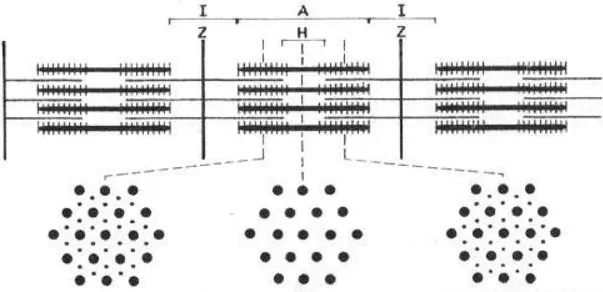

As can be seen in Fig. 2, the arrangement of actin and myosin filaments corresponded well to the pattern of cross-striation observed under a light microscope, consisting of alternate anisotropic A-band and isotropic I-band with central Z-line. The arrangement of actin and myosin filaments indicates not only the structural basis of cross-striations but also its functional significance.

Figure 2 Hexagonal arrangement of thick (myosin) and thin (actin) filaments in vertebrate skeletal muscle. For further explanation, see text.

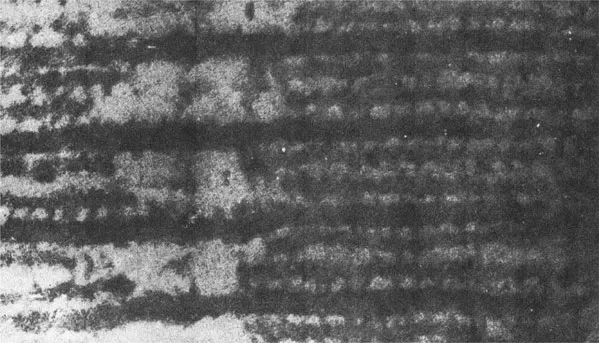

In the longitudinal section of vertebrate skeletal muscle, H. E. Huxley noticed the existence of cross connections between actin and myosin filaments (Fig. 3). When I first invited him to a muscle symposium that I organized, he told me, “As soon as I found cross connections between the two filaments, an idea occurred to me that the filaments slide past each other by the action of these cross connections.” Although the cross connections he observed at that time now appear to be an artifact arising from the compression of longitudinal sections due to incomplete techniques to prepare ultrathin sections, it does not affect his deep insight into the mechanism of muscle contraction, which I believe to be an incarnation of human wisdom.

Figure 3 Electron micrograph showing part of A-band where actin and myosin filaments run in parallel with each other. Note cross connections between actin and myosin filaments. From Huxley (1953).

During the course of his pioneering electron microscopic work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the only place in the world where investigators were allowed to use the electron microscope for biological research, H. E. Huxley met J. Hanson, an expert of phase-contrast microscopy, and they started working together productively using myofibrils isolated from the vertebrate skeletal muscle. Their findings (Hanson and Huxley, 1953; Huxley and Hanson, 1954) are summarized as follows: (1) When myofibrils are activated to shorten with ATP, the I-band width decreases, while the A-band width remains unchanged. (2) The magnitude of decrease in the I-band width at both sides of the A-band is equal to the decrease in the width of H-zone, i.e., the less dense region at the center of the A-band. (3) When myosin is extracted from myofibrils with high ionic strength solution, the dense material in the A-band is removed.

These results clearly indicate that (1) the two contractile proteins, actin and myosin, are present in the muscle in the form of two different filaments, i.e., actin and myosin filaments; (2) myosin filaments are located in the A-band, while actin filaments extend in either direction from the Z-line to penetrate in between myosin filaments; and (3) muscle contraction is caused by relative sliding between actin and myosin filaments, in such a way that the amount of overlap between the filaments increases; and (4) the length of actin and myosin filaments remains unchanged during muscle contraction. Thus, the cross-striations are shown to have structural and functional significance. The region between the adjacent Z-band is called the sarcomere and is regarded as the functional unit of the muscle. More exactly, the half-sarcomere is the functional unit, since the sarcomere is symmetrical at both sides of the A-band center, i.e., the H-zone.

1.3 Myofilament Structure and Possible Role of Myosin Heads in Producing Myofilament Sliding

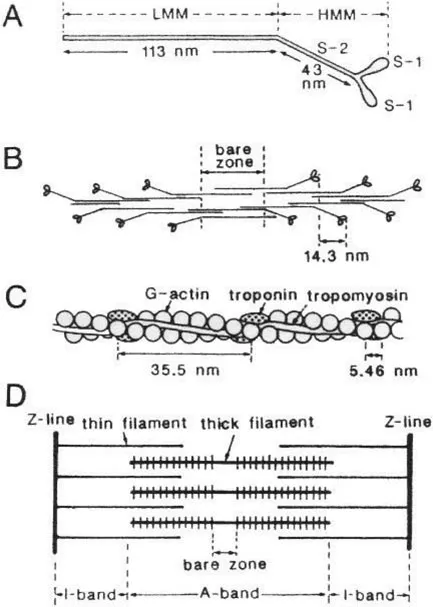

Considerable progress has been made concerning the structure and function of actin and myosin filaments as well as actin and myosin molecules. As shown in Fig. 4A, a myosin molecule (MW 450,000) consists of two pear-shaped heads and a 156 nm-long rod, and can be split into two parts: the 113 nm long rod, known as light meromyosin (LMM), and the rest of the molecules, containing the two heads and the 43 nm-long rod, known as heavy meromyosin (HMM). HMM can be further split into two separate heads (subfragment-1 or S-1) and the rod (subfragment-2, S-2). In myosin (thick) filaments, LMM aggregates to form the filament backbone, which is polarized in opposite directions on either side of the filament central point, while myosin heads (S-1) extend laterally from the filament backbone with an axial interval of 14.3 nm, except for a region without myosin heads, i.e., the bare zone at the center of myosin filament (Fig. 4B). The S-2 rod is believed to serve as a hinge between myosin heads and the myosin filament backbone, thus enabling myosin heads to swing away from the myosin filament.

Figure 4 Structure of myosin and actin molecules and their formation of myosin and actin filaments. (A) Diagram of myosin molecule. (B) Arrangement of myosin molecules in myosin filament. (C) Structure of actin filament. (D) Arrangement of actin and myosin filaments in a sarcomere. Note that half-sarcomere is the structural and the functional unit of striated muscle. From Sugi (1992).

On the other hand, actin (thin) filaments primarily consist of two helical strands of globular actin monomers (G-actin, MW 41,700), which are wound around each other with a pitch of 35.5 nm. The axial separation of actin monomers in the actin filament is 5.46 nm (Fig. 4C). In the vertebrate skeletal muscle, actin filaments contain tropomyosin and troponin, whose function will not be discussed in this book. Owing to the symmetrical sarcomere structure, the direction of filament sliding is reversed across the bare zone (Fig. 4D). Since the establishment of the sliding filament mechanism in muscle contraction, the remaining central problem in understanding the molecular mechanism of muscle contraction is” What makes the filaments slide past each other?”

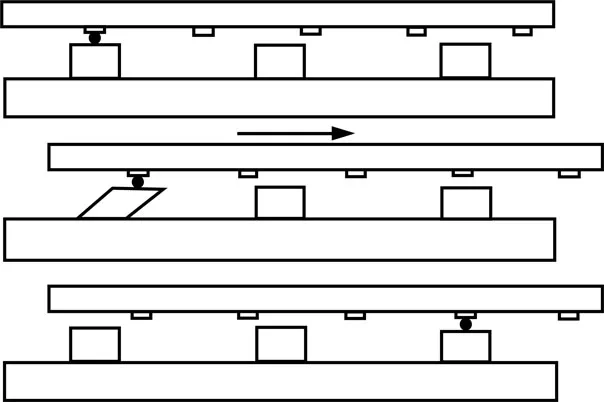

As already mentioned, H. E. Huxley got the idea that the cross connections, which he observed in his early electron microscopic observation of actin and myosin filaments (Fig. 2), and later proved to be myosin heads extending from myosin filaments, play an essential role in producing the filament sliding. In 1969, he put forward a hypothesis shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5 Proposed attachment–detachment cycle between myosin head extending from myosin filament and corresponding myosin-binding site on actin filament. From Huxley (1969).

Owing to the difference in their axial periodicity, the cyclic attachment–detachment between actin and myosin filaments takes place asynchronously. In the upper diagram, a myosin head (located on the left) first attaches to a site on an actin filament. Then, the attached head changes its configuration to produce a unitary sliding between the filaments (middle diagram). The direction of filament sliding is such that the sarcomere shortens. After producing the unitary filament sliding, the myosin head detaches from the site on actin filament (lower diagram). It is assumed that hydrolysis of one ATP molecule is coupled with each attachment–detachment cycle. It should be noted that after producing the filament sliding, myosin heads are assumed to return to their original configuration; the first myosin head movement producing the filament sliding is called the power stroke, while the subsequent myosin head movement to restore its original co...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- 1. Historical Background

- 2. Dogmas of Huxley–Simmons Model Not Supported Experimentally

- 3. New Methods and New Dogmas and Their Shortcomings

- 4. The Swinging Lever Arm Mechanism: A Most Prominent Current Dogma

- 5. Early Electron Microscopic Studies on Myosin Head Movement Using Quick-Freeze, Deep-Etch Replica Method

- 6. Electron Microscopic Recording of ATP-Induced Myosin Head Movement Using the Gas Environmental Chamber

- 7. Evidence against Current Dogmas and Mechanism of Muscle Contraction as Revealed by the Effect of Antibodies on Myosin Head

- 8. Electron Microscopic Recording of Myosin Head Power Stroke: Evidence That Myosin Heads Take the Neutral Position When Detached from Actin Filaments

- 9. The Fenn Effect: A Fundamental Mystery in Muscle

- 10. Load-Dependent Mechanical Efficiency of Myosin Head Performance

- 11. Past History-Dependence of Myosin Head Performance

- 12. Reminiscences of My Early Work: I. Summation of Force Responses in Muscle

- 13. Reminiscences of My Early Work: II. Transverse Spread of Contraction Initiated by Local Membrane Depolarization in Single Muscle Fibers

- 14. Epilogue

- References

- Index