- 241 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Personal Growth Through Adventure

About this book

First Published in 1994. Hopkins and Putnam hold a questioning and healthily sceptical attitude towards the theory and practice of adventure education, something they claim has received insufficient reflection by practitioners on the nature of the process of adventure education. This title outlines their claims that a clear and simple exposition of principles and, consequently, practice has not been well enough informed. Written to stimulate debate, the critical stance that prompted the authors' way of thinking, and so ultimately the book, has a great deal to do with the pervading attitudes at the Outward Bound schools.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Personal Growth Through Adventure by David Hopkins,Roger Putnam in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Development

Chapter 1

Personal Growth Through Adventure

A race preserves its vigour so long as it harbours a real contrast between what has been and what may be; and so long as it is nerved by the vigour to adventure beyond the safeties of the past. Without adventure, civilization is in full decay.

Alfred North Whitehead

If adventure has a final all-embracing motive it is surely this; we go out because it is our nature to go out, to climb the mountains and sail the seas, to fly to the planets and plunge into the depths of the oceans. By doing these things we make touch with something outside or behind, which strangely seems to approve our doing them. We extend our horizon, we expand our being, we revel in a mastery of ourselves which gives an impression, mainly illusory, that we are masters of our world. In a word we are men, and when man cease to do these things, he is no longer man.

Wilfred Noyce

The adventure – and it is the test of a good adventure – goes on, the same for every generation. It can lose nothing by time or repetition. The first sight of the sea, of the desert, or of a mountain, remains the first sight for each new child, and evokes afresh the same response. The passion for discovery, for the mastery of unknown difficulty, stays always the same.

Geoffrey Winthrop Young

Outdoor Education is not a subject but an approach to education which is concerned with the overall development of young people. It is an organised approach to learning in which direct experience is of paramount importance. We were pleased that the Secretaries of State accepted the potential value of outdoor education in recognising the valuable contribution it can make to the personal and social development of pupils.

National Curriculum Physical Education Working Group

These four quotations capture some of the aspirations we also have for adventure education. With Alfred North Whitehead we feel that a philosopy of adventure is vital to the preservation of a vibrant and caring society. We agree with Wilfred Noyce, the leading poet-mountaineer of his generation, on the importance of physical challenge and experience as a precursor to emotional and intellectual growth. We delight with Geoffrey Winthrop Young in his description of adventure’s most potent and enduring characteristic, its uniqueness for each individual’s experience. We are also pleased that the National Curriculum Physical Education Working Group proposals endorsed the use of the outdoors as a medium for learning. So among its other attributes, adventure education contributes to the development of society, of individuals, is essentially democratic, and constitutes a powerful and unique way of learning.

Adventure education has a long and distinguished tradition. Homer’s legend of Odysseus, for example, provides us with an archetype of the adventurer who leaves the comforts of home, civilisation and loved ones behind, strikes out into the unknown, seeks to push back the physical and geographical frontiers of his existence, and in the process probes the myths and monsters of his own mental and psychological being. Plato formalises such an image in parts of his description of the education of the Guardians in the Republic, and much later Rousseau uses it as a central theme in the development of Emile. We hear about battles being won on the playing fields of our more prestigious public schools, and despite the elitist and chauvinistic associations such claims may have for us, the notion of personal development occurring through challenge and adventure rings true. So much so that educational philosophers and psychologists such as John Dewey, Jean Piaget and Jerome Bruner have taken experience as the central building block of their theories of education. All this suggests that adventure education is not a passing fad, a whim, a gloss of the ‘true purpose of education’ but an approach to learning that has an enduring relevance in a wide variety of educational contexts.

Most people who begin to read this book will have had some experience of learning that pervades their whole being, that involves their feelings as well as their intelligence. Often these occasions will have occurred in the outdoors, where it is easier to have unifying rather than atomistic learning experiences. These are times when we have confirmed natural laws about the wind, the clouds, the water; discovered more about the human relationship with landscape; have understood more clearly the meaning of a poem or piece of literature; have been faced starkly with the personality of another; or through some physical challenge been confronted with our own strengths and weaknesses. Such occasions have often been memorable, euphoric and powerful. Although they linger long in the memory, they are often uncomfortable because we do not always know what to do with them or how to handle them. We have not developed a tradition or a language to deal with learnings like this which are integrative, holistic and fundamental. But unless we do, we will remain impoverished and myopic as learners.

Joe Nold (1978) addresses the same problem:

For learning to take place in a holistic sense there must also be intellectual reconstruction, both at a metaphoric level and eventually at an articulate level. Words define us. They have implications for self concept that are important not only as a therapeutic process but as a part of our identity. Our humaneness is expressed through articulation and language. Words free us from the immediacy of a specific experience. They permit us to develop flights of fantasy, only through words can we reach into the future, begin to establish some form of continuity and transfer, and connect the Adventure Education experience to a broader life learning continuum.

This quotation encapsulates the grandiose and ambitious task we have set ourselves in this book – to write a primer on adventure education. It feels better to have said that: it is good to begin a book honestly even if one’s aspirations are not matched by an ability to put them into practice!

Between us we have spent well over 60 years working in adventure education, connected to organisations that provide personal growth experiences for a wide range of people through outdoor activities. We feel that the effectiveness of such agencies in providing these experiences is largely a function of the clarity with which they and those working in them, understand and put into practice the philosophical and psychological principles underpinning adventure education. We believe that this understanding and practice is uneven, limited and capricious. Some people and some organisations move beyond our experience and transcend our expectations, others do not. One purpose of this book, therefore, is to provide, as succinctly and clearly as possible, an overview of the principles and practice associated with adventure education in order to help us to do our work with greater finesse, meaning and sensitivity.

Let us begin by putting some boundaries around the territory we are going to explore in the following pages. We start with a happy trinity of words which provide us with some bench-marks: adventure, education, outdoor, as seen in Figure 1.1.

The word outdoor is simply a statement about location: it describes where something happens. It is not, as some imply, a statement about an approach or a philosophy. It is wrong, we believe, to suggest that just because learning occurs in the outdoors it is inherently good or worthwhile, or that it implies a particular teaching approach, view of

Fig. 1.1 The territory of adventure education

human nature or personality development. We restrict ourselves in this book simply to a consideration of learning that occurs in the outdoors. This is not to say that what we say has no implications for learning indoors in schools, colleges, universities or work. Indeed one of the subtexts of the book is to examine the implications of adventure education for ‘mainstream’ education and career preparation. We argue throughout for a more eclectic view of teaching and learning, but our major concern is with learning out of doors.

We define adventure as an experience that involves uncertainty of outcome. An adventure can be of the mind and spirit as much as a physical challenge. It normally involves us in doing something new, of moving beyond our experience in discovering the unknown or meeting the challenge of the unexpected. We experience similar emotions when we begin to write a poem or undertake other creative activities, are involved in unaccustomed social situations, are faced with a challenging hand of bridge, begin to acquire new skills or knowledge, or begin a daunting abseil or rockclimb. All of these activities involve us in ‘extending our being’ and it is in this essential novelty that their value lies. So although we are principally involved in this book with adventurous activities outdoors this is not to imply, as we have already suggested, that other forms of learning cannot be adventurous. Indeed a major theme and a main argument of the book is to articulate how learning occurs through adventure and how adventure applies to other learning situations. We believe that all education should be adventurous, and when it is not we mourn at missed opportunities.

Our third parameter is education. To us education is a process of intellectual moral and social growth that involves the acquisition of knowledge, skills and experience. To us this includes the discipline of training, of learning skills, as well as more reflective learning episodes. The parameter of education really begins to define our area of enquiry. Education, according to R. S. Peters, the doyen of British educational philosophers, involves taking part in worthwhile activities. Peters (1966: 155) maintains that such activities have their own built-in standards of excellence, and thus ‘can be appraised because of the standards immenent in them rather than because of what they lead on to’. Peters (1966: 159) continues to argue that such activities ‘illuminate other areas of life and contribute much to the quality of living’ and ‘have a wide-ranging cognitive content’. He is referring to ‘knowing how’ rather than ‘knowing that’. He argues that the worthwhile activity, ‘constantly throws light on, widens, and deepens one’s view of countless other things’. Climbing a mountain for fun will by definition be in the outdoors, it may also be adventurous, but it may not necessarily be educative even in the broad sense in which we have defined the term. By the same token, we are arguing that not all educative experiences are restricted to institutional learning, and that much education does and can occur in non-formal settings.

Having sketched out the territory of this book we should now define our terms more clearly. We use the phrase ‘adventure education’ in the same sense that others talk about ‘development training’, ‘outdoor education’, ‘outward bound activities’, ‘adventure based counselling’, ‘outdoor development’ and so on. Although each of these phrases is acceptable we prefer ‘adventure education’ because it focuses upon the nature of the experience – adventure implies challenge coupled to uncertainty of outcome. Adventure education is consequently a more accurate description of the activities we have in mind, and fits better within the boundaries we have just described. But for ease of exposition we will often use the range of terms eclectically and interchangeably in part one and part two of the book. When we come in part three to describe specific progammes we will define the terms more contextually and respect the definitions given to these various approaches by their practitioners.

Adventure education has probably found one of its fullest and most coherent expressions in the Outward Bound movement. Indeed, the Outward Bound organisation has developed the concept and principles to such an extent that, on some occasions, the terms are occasionally if mistakenly used synonymously. We have heard of schools adopting an ‘Outward Bound’ approach to outdoor pursuits, which really means that they are utilising some principles of adventure education in their curriculum. We read of managers having had an ‘Outward Bound’ experience whilst on a training course.

It is at this point that we must come clean and declare a self interest. Outward Bound has been one of the most influential experiences in both of our lives. We both attended courses as Eskdale whilst adolescents, and subsequently Outward Bound provided one of us with a living for well over 25 years and the other with an inspiration that determined a life’s direction. We learned about adventure education through Outward Bound and have been indelibly altered by its formative influence. Although we have also taken a leading role in other outdoor and adventure organisations, notably the National Association for Outdoor Education and the British Association of Mountain Guides, our roots remain in Outward Bound. Having admitted its formative influence in our lives and signalled its importance in the development of adventure education we remain healthily critical. We also strive for balance in our exposition of the influence of Outward Bound and other similar organisations.

The history of Outward Bound is relatively well known. It dates from 1941 when Kurt Hahn, the German philospher, educator and founder of Gordonstoun, established the first Outward Bound School at Aberdovey, Wales, at the request of Lawrence Holt. It is symbolic that Outward Bound was the joint invention of Hahn, the educator with a platonic vision, and Holt, the shipping line owner with a social conscience. The confluence of the cultures of the working world and of education continues to be a vital feature of the Outward Bound movement.

Outward Bound’s post war flowering was essentially the manifestation of a romantic ideal characterised by Blake’s prophetic but rather simplistic phrase, ‘Great things are done, when men and mountains meet’. The establishing of a second school – the Outward Bound Mountain School at Eskdale in the English Lake District – in 1950 served to move Outward Bound away from the ‘service orientation’ it gained from its wartime inception, and placed the movement in the public arena. Today there are some 30 schools or centres worldwide and Outward Bound programmes have broadened to include an increasingly wide spectrum of participants. Intellectually also, Outward Bound has contributed, especially in North America, to the research and thinking on adventure education, and more generally to the growth in experiential learning approachess.

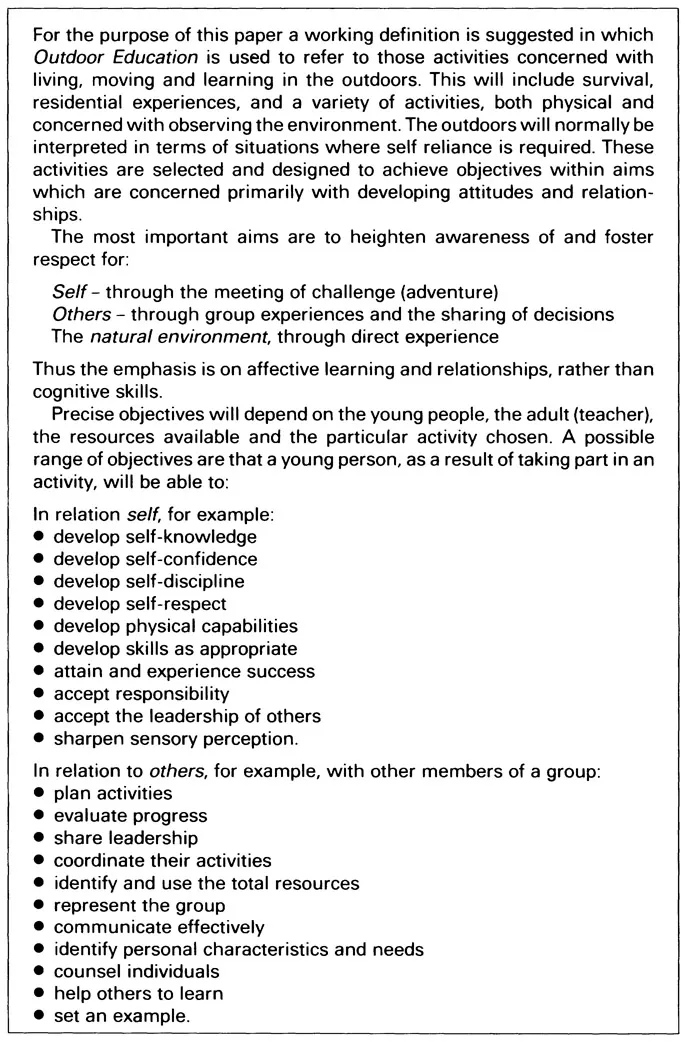

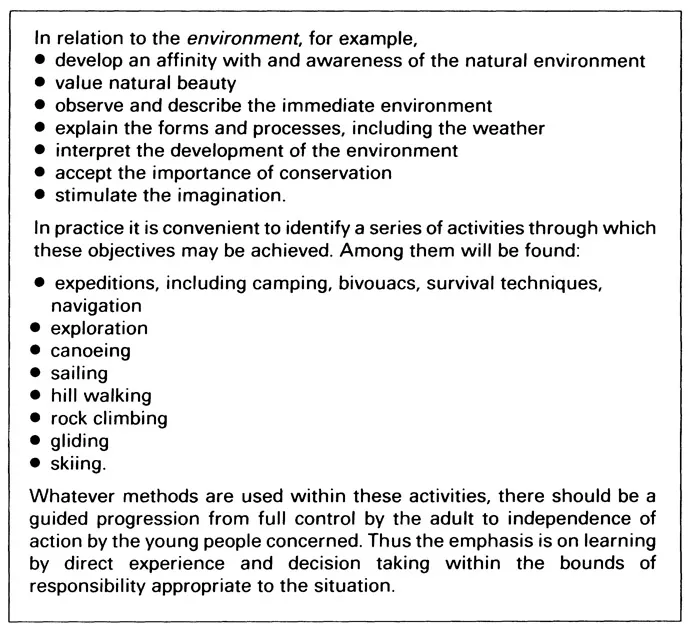

After this digression into the world of Outward Bound it is now important to continue to explore the questions of definition. Having set the boundaries and argued for semantic eclecticism, we should now move more directly into detail. As a starting point we still find the definition proposed by The Dartington Conference of 1975 enormously helpful (see Box 1.1). Although written some 18 years ago, the aims and content of outdoor education as defined by the Dartington conference participants still hold good today. In many ways the conference was a seminal event. Sponsored by the D.E.S., it brought together experienced practitioners representing a wide variety of interests and experience with the aim of ‘integrating outdoor education into an overall strategy’. The extent of their success can be

Box 1.1 Extract from Outdoor Education – the report of the Dartington Conference, October 1975 (D.E.S. 1975: 1–3)

gauged by the influence their discussions have had on the subsequent development of outdoor education in the UK, and the pertinence and freshness of their definition for the current scene.

The aims identified by the Dartington Conference are, we believe, the vital aspirations for adventure education. These aims are more fundamental than even the examples given in the Dartington report. The synthesis of T, ‘We’, ‘Environment’, provide ‘themes’that pervade and transcend the adventure education experience. Before moving directly into the substance of the book it may be instructive to reflect on them for a while.

‘I’ – the self

Having realised his own self as the SELF, a man becomes selfless… This is the highest mystery

The Maitreyana Upanishad

Although mysterious, the search for the T, the self, is an enduring quest. Central to the aspiration of adventure education programmes is the enhanced self-concept of the individual participant. Personal growth, self-actualisation and maturity are all highly prized individual goals. As we shall discuss in much greater detail later in the book, experience is the basis of self-discovery. We learn about ourselves as we learn about and interact with others and the environment in which we live.

Experiential learning has thus been taken as the most effective way of achieving self-discovery, and in one way or another provides the foundation for most adventure education programmes. Yet not all experience is good. It is important at the outset to confront this important truth head on. Even John Dewey (1938: 25), the high priest of experiential learning, said that:

The belief that all genuine education comes about through experience does not mean that all experiences are genuinely educative.

Wichmann (nd) calls the uncritical commitment to experience for experience’s sake the ‘Learning by doing heresy’. He claims that there are three syndromes t...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- About the Authors

- Preface and Acknowledgements

- PART 1 – Development

- PART 2 – Principles

- PART 3 – Practice

- PART 4 – Themes

- References

- Index