- 139 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Logic of Science in Sociology

About this book

The subject of this book is limited to the abstract form or "logic" of science, as applied particularly to scientific sociology. But the discussion presented here goes beyond abstraction and serves a practical role in the sociology and history of science by providing a framework for reducing the enormous variety of scientific researches-both within a given field and across all fields-to a limited number of interrelated formal elements. Such a framework may prove useful in assessing empirical relationships between the formal aspects of scientific work and its substantive social, economic, political, and historical aspects. This is a work of synthesis that merits close attention. It provides an area for viewing theory as something more than a review of the history of any single social science discipline.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter One

Introduction

Science and Three Alternatives

Whatever else it may be, science is a way of generating and testing the truth of statements about events in the world of human experience. But since science is only one of several ways of doing this, it seems appropriate to begin by identifying them all, specifying some of the most general differences among them, and thus locating science within the context they provide.

There are at least four ways of generating, and testing the truth of, empirical statements: “authoritarian,” “mystical,” “logico-rational” and “scientific.”1 A principal distinction among these is the manner in which each vests confidence in the producer of the statement that is alleged to be true (that is, one asks, Who says so?); in the procedure by which the statement was produced (that is, one asks, How do you know?): and in the effect of the statement (that is, one asks, What difference does it make?).

In the authoritarian mode, knowledge is sought and tested by referring to those who are socially defined as qualified producers of knowledge (for example, oracles, elders, archbishops, kings, presidents, professors). Here the knowledge-seeker attributes the ability to produce true statements to the natural or supernatural occupant of a particular social position. The procedure whereby the seeker solicits this authority (prayer, petition, etiquette, ceremony) is likely to be important to the nature of the authority’s response, but not to the seeker’s confidence in that response. Moreover, although the practical effects of the knowledge thus obtained can contribute to the eventual overthrow of authority, a very large number of effective dis- confirmations may be required before this happens.

The mystical mode (including its drug- or stress-induced hallucinatory variety) is partly related to the authoritarian, insofar as both may solicit knowledge from prophets, mediums, divines, gods, and other supernaturally knowledgeable authorities. But the authoritarian mode depends essentially on the social position of the knowledge-producer, while the mystical mode depends more essentially on manifestations of the knowl- edge-consumer’s personal “state of grace,” and on his personal psychophysical state. For this reason, in the mystical mode far more may depend on applying ritualistic purification and sensitizing procedures to the consumer. This mode also extends its solicitations for knowledge beyond animistic gods, to more impersonal, abstract, unpredictably inspirational, and magical sources, such ‘as manifest themselves in readings of the tarot, entrails, hexagrams, and horoscopes. Again, as in the case of the authoritarian mode, a very large number of effective dis- confirmations may be needed before confidence in the mystical grounds for knowledge can be shaken.

In the logico-rational mode, judgment of statements purporting to be true rests chiefly on the procedure whereby these statements have been produced; and the procedure centers on the rules of formal logic. This mode is related to the authoritarian and mystical ones, insofar as the latter two can provide grounds for accepting both the rules of procedure and the axioms or “first principles” of the former. But once these grounds are accepted, for whatever reasons, strict adherence to correct procedure is held infallibly to produce valid knowledge. As in the two preceding modes, disconfirmation by effect may have little impact on the acceptability of the logico-rational mode of acquiring knowledge.

Finally, among these four modes of generating and testing empirical statements, the scientific mode combines a primary reliance on the observational effects of the statements in question, with a secondary reliance on the procedures (methods) used to generate them.2 Relatively little weight is placed on characteristics of the producer per se; but when they are involved, achieved rather than ascribed characteristics are stressed — not for their own sakes, but as prima facie certifications of effect and procedure claims.

In emphasizing the role of methods in the scientific mode, I mean to suggest that whenever two or more items of information (for example, observations, empirical generalizations, theories) are believed to be rivals for truth-value, the choice depends heavily on a collective assessment and replication of the procedures that yielded the items.3 In fact, all of the methods of science may be thought of as relatively strict cultural conventions whereby the production, transformation, and therefore the criticism, of proposed items of knowledge may be carried out collectively and with relatively unequivocal results. This centrality of highly conventionalized criticism seems to be what is meant when method4 is sometimes said to be the essential quality of science; and it is the relative clarity and universality of this method and its several parts that make it possible for scientists to communicate across, as well as within, disciplinary lines.

Scientific methods deliberately and systematically seek to annihilate the individual scientist’s standpoint. We would like to be able to say of every statement of scientific information (whether observation, empirical generalization, theory, hypothesis, or decision to accept or reject an hypothesis) that it represents an unbiased image of the world — not a given scientist’s personal image of the world, and ultimately not even a human image of the world, but a universal image representing the way the world “really” is, without regard to time or place of the observed events and without regard to any distinguishing characteristics of the observer. Obviously, such disembodied “objectivity” is impossible to finite beings, and our nearest approximation to it can only be agreement among individual scientists. Scientific methods constitute the rules whereby agreement about specific images of the world is reached. The methodological controls of the scientific process thus annihilate the individual’s standpoint, not by an impossible effort to substitute objectivity in its literal sense, but by substituting rules for intersubjective criticism, debate, and, ultimately, agreement.5 The rules for constructing scales, drawing samples, taking measurements, estimating parameters, logically inducing and deducing, etc., become the primary bases for criticizing, rejecting, and accepting items of scientific information. Thus, ideally, criticism is not directed first to what an item of information says about the world, but to the method by which the item was produced.

But I have stressed that reliance on the observational effects of statements purporting to be true is even more crucial to science than is its reliance on methodological conventions. By this I mean that if, after the methodological criticism mentioned above, two information components are still believed to be rivals, the extent to which each is accepted by the scientific community tends to depend heavily on its resistance to repeated attempts to refute it by observations. Similarly, when two methodological procedures are believed to be rivals, the choice between them tends to rest on their relative abilities to generate, systematize, and predict new observations. Thus, Popper says: “I shall certainly admit a system as empirical or scientific only if it is capable of being tested by experience. ... It must be possible for an empirical scientific system to be refuted by experience” (1961:40-41)

Assuming that observation is partly independent of the observer (that is, assuming that he can observe something other than himself, even though the observation is shaped to greater or lesser degree by that self — assuming, in short, that observations refer, partly, to something “out there,” external to any observer), it becomes apparent that reliance on observation seeks the same goal as reliance on method: the annihilation of individual bias and the achievement of a “universal” image of the way the world “really” is. But there is an important difference in the manner in which the two seek this goal. Reliance on method attacks individual bias by subjecting it to highly conventionalized criticism and subordinating it to collective agreement. It thus seeks to overpower personal bias with shared bias. Reliance on observation (given the “independence” assumption mentioned above), however, introduces into both biases an element whose ultimate source is independent of all human biases, whether individual and unique or collective and shared. In a word, it seeks to temper shared bias, as well as individual bias, with un-bias.

Therefore, the scientific mode of generating and testing statements about the world of human experience seems to rest on dual appeals to rules (methods) whose origin is human convention, and to events (observables) whose origin is partly nonhuman and nonconventional. From these two bases, science strikes forcibly at the individual biases of its own practitioners that they may jointly pursue, with whatever falter and doom, a literally superhuman view of the world of human experience.

Finally, in this brief comparison of modes of generating and testing knowledge, one should remember that neither the scientific, nor the authoritarian, nor the mystical, nor the logico- rational mode excludes any of the others. Indeed, a typical effort will involve some scientific observation and method, some authoritarian footnoting and documentation, some invocations of ritually purified (that is, trained) imagination and insight, and some logico-rational induction and deduction; only relative emphasis or predominance among these modes permits classifying actual cases. It is perhaps just as well so, since none of the modes can be guaranteed, in the long run, to produce any more, or any more accurate, or any more important, knowledge than another. And even in the short run, a particular objective truth discovered by mystical, authoritarian, or logico-rational (or, indeed, random) means is no less true than the same truth discovered by scientific means. Only our confidence in its truth will vary, depending on which means we have been socialized to accept with least question.

Given this initial perspective on science as compared to other ways of testing the truth of statements about the world of human experience, a more focused approach to it can be made.

Overview of Elements in the Scientific Process

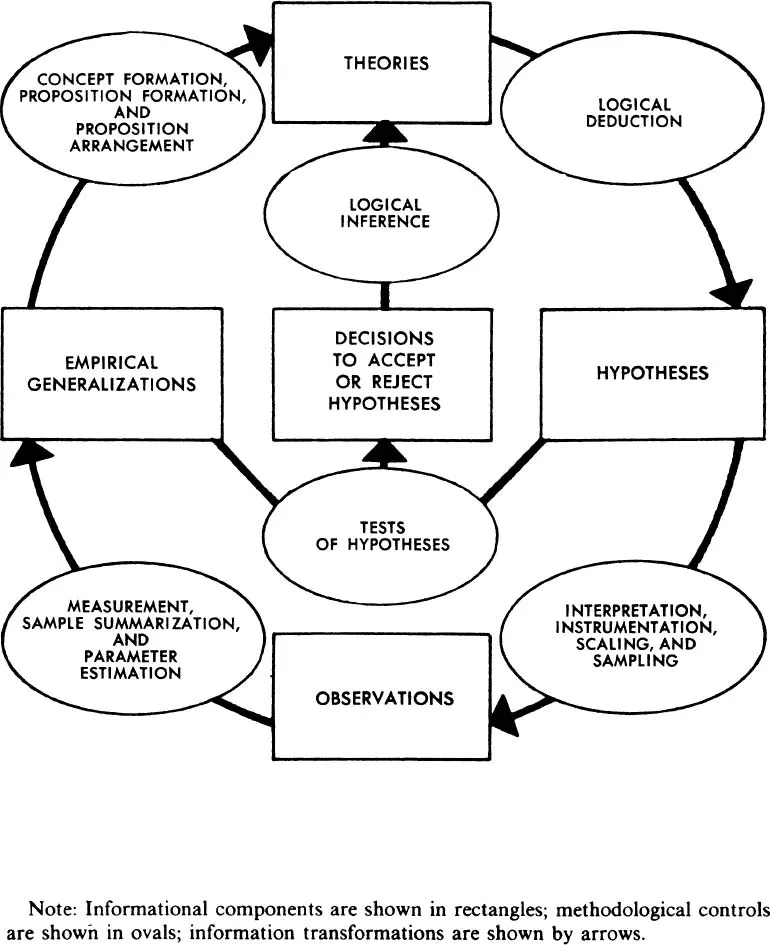

The scientific process may be described as involving five principal information components whose transformations into one another are controlled by six principal sets of methods, in the general manner shown in Figure 1. This figure is intended to be a concise but accurate map of most of the discussion in this book; for this reason, parts of it will be reproduced at appropriate points. However, the reader may wish to turn back to the complete figure occasionally in order to keep clearly in mind its full perspective. In brief translation, Figure 1 indicates the following ideas:

Individual observations are highly specific and essentially unique items of information whose synthesis into the more general form denoted by empirical generalizations is accomplished by measurement, sample summarization, and parameter estimation. Empirical generalizations, in turn, are items of information that can be synthesized into a theory via concept formation, proposition formation, and proposition arrangement. A theory, the most general type of information, is transformable into new .hypotheses through the method of logical deduction. An empirical hypothesis is an information item that becomes transformed into new observations via interpretation of the hypothesis into observables, instrumentation, scaling, and sampling. These new observations are transformable into new empirical generalizations (again, via measurement, sample summarization, and parameter estimation), and the hypothesis that occasioned their construction may then be tested for conformity to them. Such tests may result in a new informational outcome: namely, a decision to accept or reject the truth of the tested hypothesis. Finally, it is inferred that the latter gives confirmation, modification, or rejection of the theory.6

Before going any further in detailing the meaning of Figure 1 and of the translation above, I must emphasize that the processes described there and throughout this book occur (1) some-

Figure 1 The Principal Informational Components, Methodological Controls, and Information Transformations of the Scientific Process.

times quickly, sometimes slowly; (2) sometimes with a very high degree of formalization and rigor, sometimes quite informally, unself-consciously, and intuitively; (3) sometimes through the interaction of several scientists in distinct roles (of, say, “theorist,” “research director,” “interviewer,” “methodologist,” “sampling expert,” “statistician,” etc.), sometimes through the efforts of a single scientist; and (4) sometimes only in the scientist’s imagination, sometimes in actual fact. In other words, although Figure 1 and the discussion in this book are intended to be systematic renderings of science as a field of socially organized human endeavor, they are not intended to be inflexible. The task I have chosen is to set forth the principal common elements — the themes — on which a very large number of variations can be, and are, developed by different scientists. It is not my principal aim here to analyze these many possible and actual variations; I wish only to state their underlying themes. Still, it seems useful to discuss briefly the types of variation mentioned above (particularly the last type), if only to defend the claim that my analysis of themes is flexible enough to incorporate, by implication, the analysis of variations as well.

Each scientific subprocess (for example, that of transforming one information component into another, and that of applying a given methodological control) almost always involves a series of preliminary trials. Sometimes these trials are wholly imaginary; that is, the scientist manipulates images in his mind of objects not present to his senses. He may think, “If I had this sort of instrument, then these observations might be obtained; these generalizations and this theory and this hypotheses might be generated; etc.”; or perhaps, “If I had a different theory, then I might entertain a different hypothesis — one that would conform better to existing empirical generalizations.” When these imaginary trials, sometimes running several times through the entire sequence of scientific transformations, seem to be accomplished all in one instant (and when, of course, these imaginary trials turn out, when actualized, to be correct and fruitful), the scientist’s performance is said to be “insightful.” It is here, in making imaginary trials, that “intuition,” “intelligent speculation,” and “heuristic devices” find their special usefulness in science.

For maximum social acceptance as statements of truth by the scientific community, trials must not be left to imagi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Full title

- Copyright

- Acknowledgments

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Observations; Measurement, Sample Summarization, and Parameter Estimation; Empirical Generalizations

- 3 Empirical Generalizations; Concept Formation, Proposition Formation, and Proposition Arrangement; Theories

- 4 Theories; Logical Deduction; Hypotheses; Interpretation, Instrumentation, Scaling, and Sampling

- 5 Tests of Hypotheses; Decisions to Accept or Reject Hypotheses; Logical Inference; Theories

- 6 Theories

- 7 Conclusions

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Logic of Science in Sociology by Walter Wallace in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.