![]()

Team Stress in Palliative/Hospice Care

Mary L. S. Vachon

SUMMARY. Using data gathered as part of a larger study of occupational stress, the subset of hospice providers was analyzed to ascertain the stressors and manifestations of stress they encountered in their work. Stressors were seen to evolve not so much from work with clients and families, but from the work environment and occupational role. Manifestations of stress were seen to consist of staff conflict, feelings of depression, grief and guilt, job/home interaction, and feelings of helplessness.

According to the standards of the National Hospice Organization (1979) the staffing prerequisites for a certified hospice require that there be a multidisciplinary team. The core members of such a team include but are not limited to: the patient/family unit; the primary physician and hospice physician; an administrator; nursing director and staff; patient care coordinator; clergy; social worker; and volunteers (Blues & Zerwekh, 1984).

Under Medicare regulations, hospice care also requires an interdisciplinary team consisting of at least one physician, one registered nurse, one social worker and one pastoral or other counselor. In addition, benefits are available for physical, occupational, and speech-language therapy; home health services by an aide who has successfully completed an approved training program; homemaker services; and bereavement, dietary, and nutritional counseling (Blues & Zerwekh, 1984; Department of Health and Human Services Health Care Financing Administration, 1982).

Although it is generally recognized that an interdisciplinary team is essential to hospice care, the stressors and stress experienced by such teams have seldom been analyzed (Mount & Voyer, 1980; Yancik, 1984a, 1984b), and most of the research studies conducted have concentrated on the stress experienced by particular team members, most often nurses (Barstow, 1980; Chiriboga, Jenkins, & Bailey, 1983; Friel & Tehan, 1980; Gotay, Crockett, & West, 1985; Gray-Toft, 1980; Krikorian & Moser, 1985; Larson, 1985; Lyall, Rogers, & Vachon, 1976; Lyall, Vachon, & Rogers, 1980; Thomas, 1983).

One of the more insightful comments made about the reality of working within an interdisciplinary hospice team is found in the work of Mount and Voyer (1980). They observed that when enthusiasts report they act as a team they should be asked to show their scars: “If they don’t have scars they haven’t worked on a team. Teams don’t just happen. They slowly and painfully evolve. The process is never complete” (Mount & Voyer, 1980, p. 466). These authors quote Rubin who stated:

It is naive to bring together a highly diverse group of people and expect that, by calling them a team, they will in fact behave as a team. It is ironic indeed to realize that a football team spends 40 hours a week practicing teamwork for the two hours on Sunday afternoon when their team really counts. Teams in organizations seldom spend two hours per year practicing when their ability to function as a team counts 40 hours per week. (Mount & Voyer, 1980, p. 466)

This paper analyzes the problems experienced by multidisciplinary hospice teams using data collected as part of a larger study of the stress experienced by caregivers to the critically ill, dying, and bereaved in a variety of settings including: obstetrics, pediatrics, oncology, hospice, critical care, emergency rooms, chronic care and bereavement work (Vachon, 1987). Because data were gathered internationally the terms hospice and palliative care are used interchangably, reflecting the different terms used in various countries. In Canada the term palliative care is more commonly employed because the term hospice translates in French to “poor house.” The term palliative care comes from the Latin palliat meaning cloaked or covered. To palliate means to alleviate without curing; to mitigate (Stein, 1969).

The data gathered show that work stress is by no means exclusive to hospice workers. Furthermore, most of the stressors caregivers report, when asked about the stress they experience in caring for the critically ill and dying, are not related directly to work with clients and their families, but rather to difficulties with colleagues and within institutional hierarchies. This article focuses on the sources of stress and its manifestations within hospice caregivers. Stressors evolve primarily from the work environment (48%), within the occupational role (29%), with patients and families (17%), and with illnesses (7%). The manifestations of stress include: staff conflict; feelings of depression; grief and guilt; job/home interaction; and feelings of helplessness.

The data presented were drawn from interviews conducted from 1980–1984 and from anecdotes gathered through lecturing, consulting, and most recently through brainstorming sessions held at the 1986 National Conference on Hospice Management: Interdisciplinary Team Development (Vachon, 1987). While anecdotes are used to illustrate particular points, the rank ordering of stressors and the data analysis presented represents the results obtained from the earlier study.

Method

Subjects

The subjects were part of a larger sample of 581 caregivers from a variety of professional groups, specialty areas, and practice settings. They were interviewed in Canada, the United States, Europe, and Australia. The description of the total sample is given in Table 1. The subsample of those in hospice work consisted of 60 interviews involving an international convenience sample of 100 caregivers including: physicians (38%); nurses (42%); social workers (13%); clergy (2%); volunteers (3%); physiotherapists (3%); and others (9%). Three percent of the sample were under 30 years of age; 45% were between 30 and 45; and 52% were over 45 years. Caregivers interviewed about hospice stress were from Canada (63%); United States (13%); Great Britain, Australia and South Africa (22%); and non-English speaking countries (2%).

Table 1

Description of Sample

Sample | Number | Percent of samplea |

Profession |

Nurses and nursing assistants | 161 | 49.00 |

Physicians | 79 | 24.00 |

Social workers | 23 | 7.00 |

Clergy | 12 | 4.00 |

Psychologists | 9 | 3.00 |

Physio/occupational therapists | 5 | 2.00 |

Volunteers | 5 | 2.00 |

Nutritionists | 5 | 2.00 |

Other (funeral directors, police, radiotherapy technologists, ambulance attendants, respiratory therapists, biomedical engineers, etc.) | 28 | 9.00 |

Sex |

Male | 95 | 29.00 |

Female | 231 | 71.00 |

Age |

20–29 years | 45 | 14.00 |

30–45 years | 162 | 50.00 |

45+ years | 115 | 35.00 |

Unknown | 5 | 2.00 |

Clinical specialtyb |

Obstetrics | 25 | 8.00 |

Pediatrics--critical care | 19 | 6.00 |

Pediatrics--chronic care | 26 | 8.00 |

Oncology | 81 | 25.00 |

Critical care--adult | 55 | 17.00 |

Emergency room | 12 | 4.00 |

Palliative care | 60 | 18.00 |

Chronic care | 13 | 4.00 |

Bereavement | 6 | 2.00 |

General | 25 | 8.00 |

Multiple specialties | 5 | 2.00 |

Practice setting |

University teaching hospital | 174 | 53.00 |

Community hospital | 91 | 28.00 |

Community practice | 30 | 9.00 |

Chronic care facility | 25 | 8.00 |

Hospice | 6 | 2.00 |

Other | 1 | .01 |

Country of practice |

Canada | 243 | 74.00 |

U.S.A. | 60 | 18.00 |

Other (English speaking) | 22 | 7.00 |

Other | 2 | 1.00 |

Major work focus |

Clinical | 178 | 54.00 |

Research | 2 | 1.00 |

Teaching | 3 | 1.00 |

Multiple roles | 68 | 21.00 |

Administration | 37 | 11.00 |

Other | 39 | 12.00 |

Note. aNumbers will not always equal 100% because of rounding.

bMany of these were joint interviews representing more people than the number shown. In particular, group interviews were common in obstetrics, pediatrics, critical care, emergency, palliative care, and chronic care.

Although, most of the data were gathered outside of the United States, numerous presentations throughout the United States, as well as the 1986 National Hospice Organization Management Conference, have led the author to conclude that despite some specific differences in the United States related to reimbursement issues (e.g., third party payors) the problems experienced internationally are quite similar.

The initial study (Vachon, 1987) was designed to: (a) survey experienced caregivers to ascertain the variables within both their professional and personal lives which served as stressors, (b) discover how their stress was manifest, and (c) delineate the coping mechanisms caregivers felt were helpful in allowing them to continue to function in potentially stressful work situations. Other studies have tended to focus on less experienced caregivers (Bosk, 1979; Quint, 1967, 1968; Schmalenberg & Kramer, 1979); on those in a particular specialty (Claus & Bailey, 1980; Fox & Swazey, 1978; Harper, 1977; Marshall, Kasman, & Cape, 1982); or on the stress of one professional group (Folta, 1965; Lyall, Rogers, & Vachon 1976). The present study has a somewhat older and presumably more experienced population than is usually found in studies of staff stress. In addition, the data were gathered across professional groups and across specialty areas. This article however, focuses only on the data gathered from the hospice staff members interviewed and describes only the stressors and manifestations of stress identified. The anecdotes used were drawn from the anonymous interviews conducted for the initial study as well as at the National Hospice Organization Management Conference, they will be identified as either “survey” or “NHO.”

Procedure

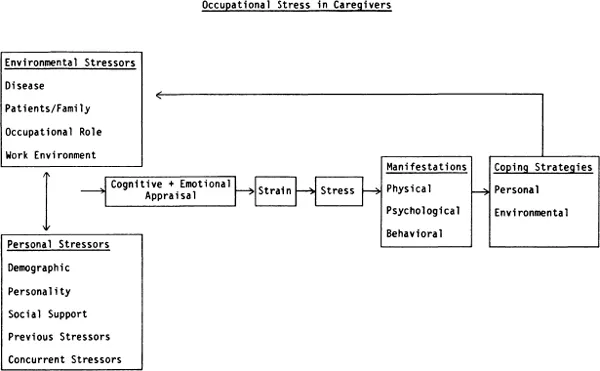

The subjects were shown a working model of a person-environment fit model of occupational stress adapted from the work of French, Rodgers, and Cobb (1974); Antonovsky (1979); Coyne and Lazarus (1980); and Folkman and Lazarus (1980). A model was initially derived from the work of these authors and then revised to reflect the subjects’ comments. The current model is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1

Note. From Occupational Stress in the Care of the Critically 111, Dying and Bereaved by M. L. S. Vachon, in press-a, New York: Hemisphere. Reprinted by permission from Hemisphere Publishing.

The data gathered from hospice caregivers were derived from 26 individual semi-structured interviews; 11 group interviews involving 51 caregivers; and 23 less formal discussions with caregivers. Subjects were asked to describe the sources of stress they experienced in working with the critically ill, dying, and bereaved. They also were asked to: (1) comment on factors from their personal lives which made them more or less vulnerable to these stressors, (2) discuss the symptoms of stress they experienced, and (3) commen...