![]()

The Collision of Military Cultures in Seventeenth-Century New England

Adam J. Hirsch

Historians of the American frontier have come to appreciate the relativity of their subject. Gone are the days when scholars portrayed the expansion of the colonial pale as a simple diffusion of European civilization into the vacuum of savage anarchy. Contemporary scholars view the frontier as a permeable barrier between two sophisticated, dynamic societies. In their model, both Indians and Europeans encountered pressure for cultural change, and both peoples underwent the process of interaction, exchange, and adjustment that anthropologists term acculturation.

Within the resulting cultural maelstrom, the role of warfare has not been clear. Many historians have treated Anglo-Indian warfare as a manifestation of cultural incompatibility between peoples, and as a principal means whereby one people was able to enforce its physical and cultural supremacy over the other. Fewer scholars have addressed warfare as a part, rather than a product, of the acculturation process.1

In fact, the ways of war constituted distinct elements of the cultures colliding in the New World. European colonists and native Indians alike devoted much attention to the practice of war, and each brought to the battlefield an elaborate code of martial conduct. Those codes expressed the “military culture” of each people, encompassing all attitudes, institutions, procedures, and implements of organized violence against external enemies. The interaction of military cultures (that is, military acculturation) shaped the history of conflict between colonists and Indians in early America. Only by examining warfare as one pattern in the mosaic of cultural contact can that history be understood. This study endeavors to analyze military conflict in seventeenth-century New England from that perspective.

The colonists who ventured to New England in the 1620s and 1630s fully appreciated the physical dangers awaiting them there. European rivals had already established several settlements within striking distance of Massachusetts, and the local Indian tribes would verge on the newcomers’ very doorsteps. William Bradford fretted that his Pilgrim community at Plymouth would be “in continual danger of the savage people,” and the Puritan leaders at Massachusetts Bay soon echoed his fears.2 New England, then, promised to be a spiritual haven, not a terrestrial one. To survive and prosper in a hostile wilderness, the “Citty upon a Hill” had to be fortified with ugly parapets and ramparts.

To ensure their physical security in America, the New England colonists relied on experts. Miles Standish, John Underhill, and other professional soldiers accompanied the settlers to supervise the defense of their plantations. Those veterans carried with them a set of rules and customs governing every detail of the practice of war. To be sure, the Puritans insisted on a number of administrative reforms, over protests from the professionals who opposed any deviation from the orthodox “Schoole of warre”3. For the most part, however, the Puritans deferred to the experts and installed a military system rooted in European tradition.

Conceptions of the overall nature and purpose of war are fundamental to any military culture. In seventeenth-century European practice, armed conflict remained a ritualized activity, regulated by a code of honor and fought between armies, not entire populations. Yet. with the rise of the nation state, warfare had developed into a massive undertaking. Waged to settle economic and religious disputes of national significance, warfare came to entail substantial expense and bloodshed. Accordingly, the New England settlers did not rejoice at the prospect of war. But if events demanded it, the settlers were determined, in Underbill’s words, to “conquer and subdue enemies.”4

To thwart enemies in time of war and provide security in time of peace, the colonists needed a fighting force, furnished with lethal weapons and versed in their use. For that service, military planners turned to a time-honored English tradition: the local militia or trainband. Every able-bodied male settler was obliged to serve in his town company, which mustered periodically for drill and mobilized at the call of the government or on alarum. To rouse the militia in the event of a surprise attack, every New England town instituted a nightly watch and designated signals to sound the call to arms.5

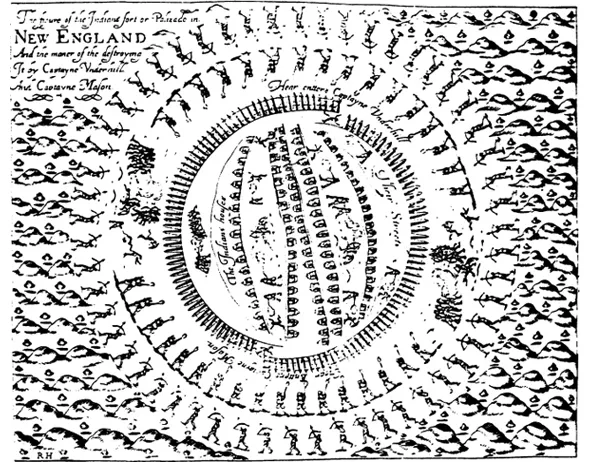

New England settlers attack Mystic village during the Pequot War, 1637. This diagram illustrates the early asymmetry in weaponry and the indiscriminate assaults on combatants and noncombatants typical of Anglo-Indian warfare throughout the seventeenth century. Reproduced from John Underhill, News from America (London, 1638).

Thus regimented, colonial militiamen received their equipment and a dose of martial training, as Standish, Underhill, and other officers labored to mold raw settlers into men-at-arms. Military apparatus and exercise in New England emphasized Old World conventions. Troopers wielded an assortment of muskets, swords, and wooden pikes. Bunched in tight formations on the open “champion field,” militiamen marched about “in rank and file” to the beat of a drum, while company colors flapped overhead. Among all values, ritual discipline reigned supreme: On the training field, if not on the battlefield, a musket might require as many as forty-two preparatory motions before it could be fired. The settlers’ evolutions, however impractical, must have made for a brilliant spectacle.6

The Indians of New England, meanwhile, had different notions about the theory and practice of war. Though as steeped in ritual as its European analogue, Indian military culture had evolved to accommodate the separate needs of aboriginal society.7

Central to Indian military culture was a distinctive conception of the purposes and objectives of armed conflict. Given ample land and a system of values by and large indifferent to material accumulation, the New England tribes rarely harbored the economic and political ambitions that fueled European warfare. Roger Williams, who knew the natives of New England better than most of his English contemporaries, traced Indian wars instead to “mocking between their great ones” or “the lusts of pride and passion.” Other observers cited retaliation for isolated acts of violence as the most common casus belli8. If waged in the name of retaliation, an Indian war ostensibly ceased when the aggrieved had inflicted retribution. Otherwise, native hostilities generally aimed at symbolic ascendancy, a status conveyed by small payments of tribute to the victors, rather than the dominion normally associated with European-style conquest.9

The organization and execution of native warfare reflected its objectives. Often the demand to take up arms came from solitary tribesmen rather than their leaders. Hostilities frequently pitted kin group against kin group rather than tribe against tribe. Summoned to the call of battle, potential combatants “gathered] together without presse or pay” and agreed to fight only after weighing the instigators’ “very copious and pathetical … Orations.” On the march, an Indian war party might melt away as individual warriors had second thoughts and returned home.10 The contrast to colonial conscription speaks in part to the limits of tribal authority, but also to the characteristics of native warfare as such: voluntary participation in hostilities followed naturally from the Indians’ individualistic motivations.

The most notable feature of Indian warfare was its relative innocuity. Williams observed of intertribal conflict:

Their Warres arc farre lesse bloudy, and devouring then the cruell Warres of Europe; and seldome twenty slain in a pitcht field: partly because when they fight in a wood every Tree is a Bucklar. When they fight in a plaine, they fight with leaping and dancing, that seldome an Arrow hits, and when a man is wounded, unlesse he that shot followes upon the wounded, they soone retire and save the wounded.

Treated to a demonstration of traditional Indian battle in 1637, Captain John Mason scoffed that “their feeble Manner … did hardly deserve the name of fighting.” New England’s native warriors apparently saw little logic in spilling oceans of blood over matters of largely symbolic importance. Their restrained efforts reflected equally restrained objectives.11

Indian battle array also contrasted sharply with European practice. Though Indians did occasionally assemble, as Williams noted, on a “pitcht field,” native warfare more frequently consisted of guerrilla raids and ambushments conducted in forested regions by small companies.12 That style of combat took maximum advantage of the natives’ renowned wilderness savvy, while also minimizing casualties.

In other respects, the Indians’ martial temperance drew their military’ culture into line with that of the colonists, whose traditions included vestiges of medieval chivalry, ingrained when the aims of Old World warfare resembled those of native conflicts. Evidence indicates native adherence to a code of honor remarkably similar to the one governing European battlegrounds. Thus, native combatants ordinarily spared the women and children of their adversaries. Tribes typically opened hostilities with a formal declaration of war rather than an unannounced assault. And on at least one occasion, sources tell of a challenge to single combat between leading sachems to settle an intertribal quarrel.13

Only in one particular was native warfare arguably more brutal than that of Europeans. Male prisoners of war frequently suffered ritual torture at the hands of their captors. Such isolated acts of cruelty did not add substantially to the death toll of native conflict and in fact may have served as emotional compensation for the participants’ prescribed restraint in combat. But while torture remained an accepted element of European jurisprudence, martial tradition held it dishonorable in the nobler trial of arms.14

Many of the contrasts between colonial and native military ordnance resulted from technological disparities rather than divergent social needs. Preparing for battle, the Indian brave donned war paint as his insignia, and he trooped off with his fellows to the sound of war cries rather than to the beat of a drum. For combat at a distance, he carried bow and arrows; for hand-to-hand fighting, a stone-headed knife or tomahawk. The mechanics of tribal security likewise coincided with more technically elaborate Puritan precautions: Round-the-clock sentries protected native villages from surprise assault, and networks of runners or other warning devices served to spread alarums. Had a fleet of menacing canoes appeared off the coast of Boston at any moment in the seventeenth century, a flurry of signal rockets and musket shots would have alerted the other settlements of impending attack. Similarly, when several shiploads of colonial militiamen cruised into Pequot Harbor on an August evening in 1636, the Indians greeted their arrival with the “most doleful and woful cries all the night (so that we could scarce rest) hallooing one to another, and giving the word from place to place, to gather their forces together.”15

What the Indians lacked in technology they made up for in the diligence with which they pursued the art of war. Like the colonists., northeastern Indians frequently relied on expert military commanders who were not necessarily the political leaders of their tribes. These native commanders, in turn, put Indian warriors through as much martial training as a colonial militiaman ever endured. In spite of such rehearsal, William Wood believed Indians to be wholly incapable of the military virtues of the Old World. But Roger Williams knew better. From his vantage point in Rhode Island, Williams testified to the “great Valour and Courage” evinced by his Narragansett Indian neighbors. And from direct experience, Williams discovered the military discipline they could display:

I once travelled (in a place conceived dangerous) with a great Prince, and his Queene and Children in company, with a Guard of neere two hundred. [T]wentie, or thirtie fires were made every night for the Guard (the Prince and Queene in the midst) and Sentinells by course, as exact as in Europe: and when we travelled through a place where ambushes were suspected to lie. a speciall Guard, like unto a Lifeguard, compassed (some neerer, some farther of[f]) the King and Queen, my selfe and some English with me.16

That Indians might exhibit formidable martial prowess was a lesson skeptical colonists often learned the hard way. Lt. Lion Gardiner suffered such a painful initiation. When his scouting party spotted three Indians in the forest during the Pequot War, “they pursued till they were brought into an ambush of fifty, who came upon them, and slew four of their men, and had they not drawn their swords and retired, they had been all slain. The Indians were so hardy, as they came close up to them, notwithstanding their pieces.” Gardiner eventually came to rate his tribal adversaries as better soldiers than the Spaniards.17

Quite plainly, the natives of New England took their warfare every bit as seriously as the newcomers, however symbolic their objectives or bloodless the results. One student has characterized intertribal conflict as “a vigorous game,” but that seems ethnocentric.18 From the standpoint of the participants, symbolic victories had significance, and bloodless battles were more than a diversion. Still, the overall patterns of native and European military cultures differed widely—and those cultures soon met head on in the New World.

The process whereby European and Indian military cultures adapted to ...