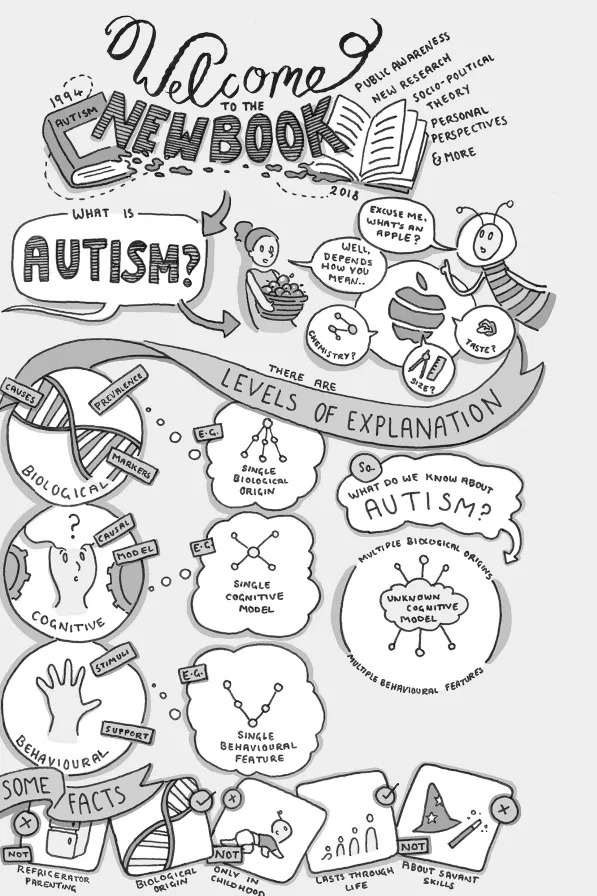

ORIGINALLY PUBLISHED IN 1994, this book has now been rewritten and updated dramatically to reflect the significant strides that have been made, not just in psychological research and theory but in socio-political theorising about autism, and in public awareness and acceptance. Nevertheless, the aim of this book remains the same – to acquaint you with current research and thinking about autism in a concise yet comprehensive way. We focus particularly on the cognitive level of explanation, which is the purview of psychological research. At the end of each chapter, recognising the fast pace of thinking about autism, we highlight current “big questions” for the field. In each chapter, we have also invited autistic people to provide their personal perspectives. These sections will, we hope, contextualise the content by providing relevant insights into the lived experience of autism. Our goal is to ensure that this academic text is firmly embedded in real-world, community priorities.

Further reading is suggested in two ways – references in the text will allow you to find out more about specific issues raised, while suggested reading (usually in the form of books or review articles) appears at the end of each chapter, allowing you to deepen your knowledge of those aspects of autism that particularly interest you. Throughout the book, discussion has been kept as brief as possible in the hope that the book will provide a manageable overview of autism, tying together a number of quite different areas. It should whet your appetite for the more detailed consideration of specific aspects of autism provided by the suggested readings.

1. Levels of explanation

If a Martian asked you what an apple is, you might reply that it is a fruit or that it is something you eat, you might describe it as roundish and red, or you might try to give its composition in terms of vitamins, water, sugars and so on. The way you answer the question will probably depend on why you think the Martian wants to know – are they hungry, do they want to be able to recognise an apple or are they simply curious? None of these answers is the answer, since each answer is appropriate for a different sense of the question. Similarly, different types of answer can be given to the question, “What is autism?” In order to find the right answer for the question in any one context, we need to think about our reasons for asking. One can think about this distinction between the different senses of a question in terms of different levels of explanation.

In the academic study of autism, three levels in particular are useful; the biological, the cognitive and the behavioural. It is important to keep these levels distinct, because each of the three levels does a different job in our understanding of autism. So, for example, to inform the search for possible causes of autism, it may be appropriate to look at biological features, while to address family priorities, it may be more important to consider the behavioural description.

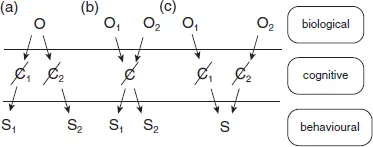

Morton and Frith (1995) introduced a specific diagrammatic tool for thinking about levels of explanation in developmental conditions such as autism. Figure 1.1, taken from Morton and Frith (1995), shows their causal models of the three levels and the possible relations between these levels in different diagnostic categories. Pattern (a) is the case of a condition defined by its unitary biological origin, which may have diverse effects at the cognitive and behavioural levels. An example of this type of condition might be Fragile X syndrome, as currently conceptualised; Fragile X syndrome is diagnosed in the presence of a specific gene mutation on the X chromosome. However, not all individuals so defined have the same cognitive or behavioural features; while many will have severe learning difficulties and social anxiety, others may have an IQ score in the average range and appear socially confident.

Pattern (b) shows a condition with multiple biological causes, and several different behavioural manifestations, but a single defining cognitive feature. Dyslexia, according to some cognitive theories (e.g. Hulme & Snowling, 2016), may be an example of such a condition. A number of biological causes may converge in causing a cognitive difference in the phonological system, leading in turn to multiple behavioural difficulties (e.g. with reading, spelling, auditory memory, rhyme and sound segmentation). Many attempts have been made to characterise autism in this way (see Chapter 6).

Pattern (c) is the case of a condition defined by its behavioural features alone, with multiple biological causes and cognitive natures. Conduct disorder, as currently diagnosed, may be such a condition; children who show antisocial behaviours, for whatever reason, may be grouped together under this label for the purposes of understanding and support.

Figure 1.1 Causal models of three types of disorder

Throughout this book, we will be using the notion of levels of explanation, to keep separate different issues and questions. In Chapter 3, the diagnosis of autism is discussed, and the focus is on the behavioural level – since autism is currently recognised on the basis of behavioural features rather than, for example, biological etiology. In Chapter 4, the biological level is addressed, since research suggests that ultimately autism is rooted in genetic factors. In subsequent chapters the remaining of the three levels is discussed – the cognitive level.

Cognitive theories aim to span the gulf between biology and behaviour – between the brain and action – through hypotheses about the mind. This level, the level of cognition, is the primary focus for this book. The term cognitive is used here not in contrast to affective; we do not promote a dichotomy of ‘rational’ versus ‘emotional’ states. Rather, it is intended to cover all aspects of the working of the mind, including thoughts and feelings. This level of analysis might also be called the “psychological” level, except that psychology also includes the study of behaviour.

Keeping the three levels of explanation (biology, cognition, behaviour) distinct, helps in thinking about a number of issues to do with autism. So, for example, people often ask whether autism is part of the ordinary continuum of social behaviour – are we all “a little bit autistic”? The answer to this question is likely to be different at the different levels of explanation. At the behavioural level the answer may appear to be “yes”, at least in some respects. For example, an autistic person may behave much like a very shy, but non-autistic, person in some situations. Nearly everyone – autistic or not – has some motor stereotypies (e.g. finger tapping). Here, the uniquely autistic experience may be to do with quality and how such behaviours co-occur. For example, the difference between one person’s sensory sensitivity to artificial lighting and another person’s autism is not simply a matter of intensity of reaction, but of patterning and complexity.

At the biological level, the answer is also complicated. In some cases, autism is linked to rare genetic mutations, not present in neurotypical individuals. However, in most cases, the genetics of autism is more like the genetics of height; lots of common genetic variants contribute to the outcome for an individual. It appears that these common variants, each of tiny effect, contribute both to diagnosed autism and to subclinical traits. At the cognitive level, too (depending on the theory you endorse), autistic people may be quite distinct from the neurotypical range. So, for example, very different cognitive reasons may underlie apparently similar behaviour by individuals with and without autism – think of an autistic person and a “normal” rebellious teenager, both of whom may dress unconventionally for a job interview. Likewise, an autistic child’s social difficulties might have a quite different cause (at the cognitive level) from a non-autistic shy person’s – although the behaviours produced (avoiding large groups, social anxiety, limited eye contact) may be very similar. We’ll return to this interesting question in Chapters 8 and 9.

At the cognitive level of explanation, in Chapter 5, we will first provide an overview of how the cognitive level may be used to link behavioural and biological features. We will review criteria for a good psychological theory, considering quality and quantity of evidence and practical impact. Subsequently, Chapters 6–8 will describe and evaluate the available cognitive models of autism in three distinct groups. Primary deficit models attempt to identify a single difference (nearly always characterised as a deficit), which has a root, causal role in determining autism. Developmental progress models tend to frame autism as the result of multiple interacting processes across early development. Cognitive difference models are concerned with the complex ways in which people with autism relate to their environments and attempt to characterise autism on that basis.

In the final two chapters of the book, we will review the contribution that psychological theory has made to our understanding of autism and to practice in schools, clinics and beyond. This will include a discussion of alternative approaches to understanding autism – e.g. sociological models – and the possibility that our biological-cognitive-behavioural framework would benefit from the addition of a fourth level of explanation. In Chapter 10, we wrap up with a discussion of the key issues for the future of autism research.

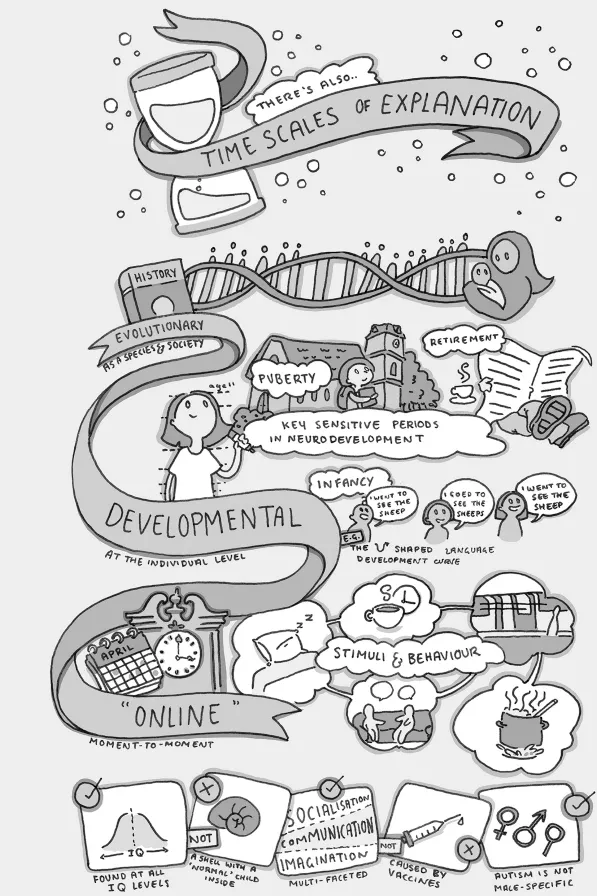

2. Timescales of explanation

As well as trying to answer the question, “What is autism?”, this book explores why or how autism occurs. In other words, this book is concerned with causal theories of autism. In thinking about causal explanations, it is useful to keep distinct not only three levels of description but also three timescales. Causes can be examined in terms of evolutionary time, taking as the unit for discussion the gene and considering pressures acting in the process of natural selection. A second timescale of cause is development, where the individual (or the biological, behavioural or cognitive mechanism within the individual) is considered. Developmental time includes key features like the existence of sensitive periods in some systems, where a specific window of time may exist for specific causes to have specific effects (e.g. imprinting in the chick) – the same causal agent acting on the organism after this time will not have the same consequences. Lastly, there is the time span of “online” mechanisms – that is moment-to-moment or processing time.

In considering autism, the latter two timescales are particularly important (see, for example, Chapters 6 and 7). An example may help to clarify the distinction and to illustrate that the same influence may have rather different effects in terms of disruptions to development and disruptions to processing.

Think of the effects of large quantities of alcohol acting as a cause on the three timescales. In evolutionary time, imagine that the existence of alcohol in foodstuffs leads to the selection of individuals with the ability to taste this substance and avoid consuming large quantities of foods containing alcohol – since being drunk does not increase reproductive success! In developmental time, alcohol has different effects – in large quantities, it may hamper the physical and mental development of the foetus. Later in the life course, but still in developmental terms, intake of large quantities of alcohol may have long-term effects on adults, for example, cirrhosis of the liver. In terms of processing time, however, the effects of alcohol are usually pleasant – that’s why we drink it! In large amounts, though, it has effects on our behaviour, for example, causing slurring of speech and loss of balance. These are “online” effects in the sense that they persist only for so long as the maintaining cause is there – the high blood alcohol level. The developmental effects, however, will persist, even after the individual has sobered up. This example may seem a long way from autism but, as will emerge in Chapters 7 and 8, psychological theories of autism can be very different depending on whether they focus on developmental or processing causes.

In the context of autism research, we might also ‘zoom in’ on the developmental timescale a little more closely. Autism is characterised as a ‘neurodevelopmental’ condition, meaning that it emerges from differences in brain development. Two key lessons emerge from this characterisation of autism. One is that any research needs to take into account the chronological age of the participants and, if different, their developmental level too. Without this context, it is impossible to determine whether a behaviour is typical or atypical, delayed or divergent, concerning or not. Take as an example the typical child’s learning of irregular past tenses, which follows a u-shaped curve. In early development, children learn and imitate the correct irregular forms of verbs and plurals (e.g. “we went to the park”; “I saw two sheep”). Later, as children, from about 2 years, start to recognise and apply grammatical rules, they tend to overgeneralise these, making charming over-regularisation errors (“we goed to the park”; “I seed two sheeps”). And later still, children competently apply grammatical rules and have learnt the cases where an irregular form is correct.

We can see from this example how important it is to understand the developmental stage reached by an individual before passing judgement on their competence. Developmental processes do not necessarily follow simple upward trajectories from less to more skilled. Moreover, the same pattern of behaviour (in this case, correct use of irregular word forms) may be apparent at different stages for different reasons (in this case, mimicry versus mastery). One relevant example more specific to autism relates to the prevalence of restricted and repetitive behaviours in children: a large survey of typically developing toddlers showed that behaviours like lining up toys, hand- flapping and specific narrow interests are very common in 2-year-olds (Leekam et al., 2007). This kind of information is essential when, among other things, attempting to identify markers of autism in early development. Understanding how and why children engage in such patterns of behaviour can also play a role in understanding the possible function of these repetitive movements and activities in the life of someone with autism.

Developmentally sensitive research is vital for at least three reasons. First, longitudinal studies help untangle cause and effect, and move us beyond inspecting correlation to inferring causation. We’ll see this in Chapter 7, where we look at studies of infants genetically predisposed to autism. Second, developmental trajectories can uncover importantly different sub-groups and help distinguish ‘phenocopies’. For example, although many of the young children adopted from terrible deprivation in Romanian orphanages showed autistic- like behaviours, most grew out of these in a way not typical of autism. Third, cross-sectional research that takes a ‘snapshot’ at one age is subject to confounds, including cohort effects. This is very relevant to the study of ageing in autism, discussed in Chapters 3 and 10, because diagnostic criteria were much narrower in the 1960s and ’70s than today, the picture we see in autistic 60-year-olds diagnosed in chil...