eBook - ePub

Handbook of Cognitive, Social, and Neuropsychological Aspects of Learning Disabilities

Volume 2

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Handbook of Cognitive, Social, and Neuropsychological Aspects of Learning Disabilities

Volume 2

About this book

First Published in 1986. This is the companion volume to the Handbook of Cognitive, Social, and Neuropsychological Aspects of Learning Disabilities-Vol. 1. As such, it is a continuation of the theme and approach taken in the first volume. There are four thematic sections, comprised of three to four chapters each, dealing with cognitive (micro-level and macro-level), social, and neurological characteristics of learning-disabled individuals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Handbook of Cognitive, Social, and Neuropsychological Aspects of Learning Disabilities by S. J. Ceci,Stephen J. Ceci in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Topic

EducationSubtopic

Education GeneralI

Microlevel Cognitive Aspects of Learning Disabilities

1

An Information-Processing Framework for Understanding Reading Disability

Yale University and Southern Connecticut State University

Yale University

Several years ago, when the senior author of this chapter taught in a resource room for learning-disabled children, she made a disturbing discovery. This discovery involved the reading-disabled youngsters, who comprised the majority of the children in the program. All these youngsters entered the program with poor decoding skills, but once exposed to the intensive phonic program used in the resource room, they generally learned to decode individual words with alacrity; that is, they could grasp phonic rules, memorize sounds for various letters and letter combinations, and apply the rules and sounds when reading individual words. The disturbing thing, particularly to someone who had had excessive faith in the curative powers of a phonic approach to teaching reading, was that the children continued to be poor readers. Now, however, their difficulties involved higher level aspects of reading. Their oral reading was discontinuous, effortful, and sometimes painfully slow; their reading comprehension was frequently poor; and the older children lacked the study strategies so important for success in content area subjects such as social studies and science.

It soon became clear to the co-author that remediation of reading disability was going to be a considerably more complex and lengthy process than she had originally thought. The presence of the higher level reading deficits also raised some troubling theoretical questions. In particular, did the reading-disabled children start out with high-level cognitive deficits that became obvious only as more demanding reading tasks were encountered? If so, the distinction between these kinds of individuals and the mentally retarded, so firmly maintained by professionals in the field of learning disabilities, became much harder to defend. Or were the higher level deficits of the reading-disabled children somehow the result of their lower level reading problems? If the latter case were true, how did the higher level deficits arise and how might instruction repair them?

In this chapter, we seek to resolve some of those questions by examining a wide range of experimental findings. Although there is no lack of research on the subject of reading disability, much of it is so labyrinthine and contradictory as to cause a Talmudic scholar to throw up his hands in despair. Borrowing an analogy, which has been used elsewhere in regard to verbal comprehension (Sternberg & Powell, 1983), but which is equally apt for reading disability, we can liken research in this field to the Indian folktale about the blind men and the elephant. In the folktale, one blind man feels the elephant’s trunk and proclaims that the elephant is just like a snake; another feels the elephant’s side and asserts that the elephant is like a wall; and so on, with each blind man contributing a different, only partially correct opinion on the nature of the elephant. Clearly, a theoretical framework is needed that will be specific enough to be helpful to both researchers and practitioners but broad enough to enable us to see the whole elephant. In this regard, verbal deficit theory (Vellutino, 1979) is a major step in the right direction. Information-processing models of reading (LaBerge & Samuels, 1974) and interactive–compensatory models (Perfetti & Roth, 1980; Stanovich, 1980) also have important implications for the study of individual differences in reading. This chapter attempts to combine findings related to these and other models into a coherent theoretical framework for understanding reading disability.

We have restricted ourselves to reading disability, rather than also considering learning disabilities in other areas such as mathematics, for two reasons. First, reading disability has been the focus of most learning-disabilities research, although in recent years this has started to change. In addition, the learning-disabilities category is so heterogeneous that a single framework for comprehending it is beyond the scope of the chapter, if not doomed to failure from the start. We also need to explain what we mean by the term reading disability (RD). In using this term, we refer to individuals who have a specific deficit in reading, coupled with average or above-average intelligence. (Although we would agree, theoretically, that RD can also occur in individuals of below-average intelligence, the difficulties inherent in disentangling the reading deficits from general cognitive deficits preclude the consideration of the low-intelligence population for the present.) We further conceptualize reading disability as an intrinsic deficit, one not caused by (but perhaps exacerbated by) external factors such as poor teaching, environmental deprivation, and so on; or by other handicapping conditions, such as sensory impairment or emotional disturbance. This exclusionary “definition” of RD is, of course, highly traditional (Johnson & Myklebust, 1967; Kirk, 1962; Orton, 1937). Essentially, it is the same as the federal register (PL 94–142) definition used by public schools in this country to identify children with learning disabilities (LD). This traditional way of conceptualizing LD and RD has obvious shortcomings, but given the state of the art, it is probably as good a definition as any other.

The problem of defining a sample is but one of many methodological difficulties involved in interpreting and carrying out research on reading disability. Many of the studies that presently exist are difficult to interpret because of incomplete information about the sample and other methodological flaws. If researchers begin to include standard information about certain “marker variables” (Keogh, Major, Omori, Gandara, & Reid, 1980), future studies will be much easier to interpret. Some excellent guidelines for conducting research in this area have been suggested by Vellutino (1979). In our view, some minimal requirements are as follows: IQ scores, with means and standard deviations, should be provided for both the reading-disabled and control groups; reading achievement scores, with means and standard deviations, should also be provided for both groups; all groups should receive the same IQ and achievement measures; the researcher should control IQ in the statistical analyses, or at least match the groups on IQ; and the reading-disabled group should be significantly below grade level in reading—at least 1 year below grade level for children in grades one through four, and at least 2 years below grade level for children in fifth grade and above. A nonverbal IQ measure is highly desirable, especially for older reading-disabled individuals, but is not often used by researchers. Similarly, although statistical control of IQ (e.g., through the use of multiple- and partial-correlation methods) is more desirable than IQ matching, because regression-to-the-mean causes serious problems with the latter, until very recently it has been only rarely employed by researchers.

Some authors (e.g., Hall & Humphreys, 1982) have raised questions about the validity of other aspects of reading-disability research, such as questioning the inclusion of children who are behind in mathematics as well as in reading. However, we think it is important to acknowledge the extraordinary practical difficulties involved in doing research on learning disabilities, in general, and reading disability, in particular. It would be possible to become so zealous about methodology that one would never actually complete any new work. Our argument is not with the technical correctness of these authors’ criticisms, but with what can reasonably be accomplished. Moreover, the problems discussed so far, which are specific to research on reading disability, are in addition to a host of other difficulties attendant on conducting any research in schools: getting administrators to return one’s phone calls, getting parental permission, scheduling, attrition, and so forth.

Finally, a few words about the organization of this chapter are in order. In the next section, we review some of the major results of existing research on reading disability. As many other detailed reviews of the literature in this field already exist (e.g., Vellutino, 1979; Worden, 1983), we have concentrated on summarizing and organizing a range of findings, rather than elaborating on results in any one particular area. The third and final section of the chapter presents a theoretical framework for understanding these results, along with some practical implications for those who work with reading-disabled individuals.

Literature Review

This literature review comprises three levels of organization. The first level is topical; the results are grouped according to the type of skill studied and whether the processing required is primarily top-down or bottom-up in nature. Top-down processing is conceptually driven, or guided by higher level processes, whereas bottom-up processing is data-driven, or guided by lower level processes. (A crucial point to bear in mind, however, and one to which we return to later, is that bottom-up deficits may affect top-down processing, and vice versa.) The findings we review fall into three skill areas: reading, language, and memory. Thus, the first section of the review deals with reading skills that involve top-down processing (e.g., comprehension), and the second section deals with reading skills that involve bottom-up processing (e.g., decoding of single words). Subsequent sections are Language: Top-down Processing, Language: Bottom-up Processing, Memory: Top-down Processing, and Memory: Bottom-up Processing.

In a second tier of organization within each skill area, results are further grouped according to whether the reading-disabled group’s performance was statistically comparable to that of the control group’s, or instead, statistically deficient. We believe that accounting for the areas of sameness is especially crucial for theoretical purposes, as the areas of deficit are often open to interpretation that depends on the overall pattern of sameness and difference.

A third level of grouping organizes the results as high confidence, middle confidence, or low confidence. We made judgments about confidence levels not only by considering the criteria discussed earlier for reading-disability research, but also by considering the extent to which the results have been replicated, especially by more than one group of researchers. Although our identification of some of the skill areas is open to debate, the confidence judgments will doubtless inspire the most controversy. Many times these judgments were not easily made. Without them, however, it is impossible to make any sense of the findings in this field.

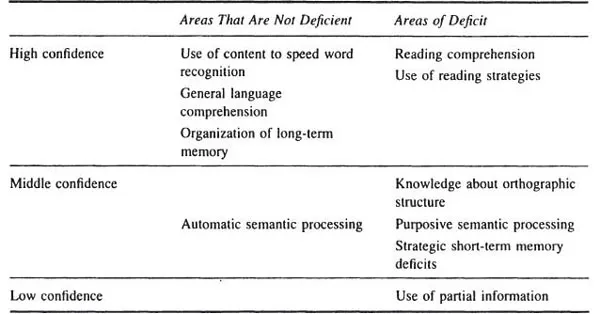

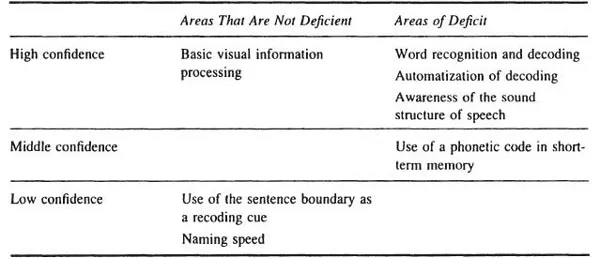

Finally, we have included two tables that summarize the results of the literature review. Table 1.1 summarizes research findings involving skills that require primarily top-down processing. Table 1.2 summarizes research findings involving skills that require primarily bottom-up processing. Frequent reference to the tables during the literature review should prove helpful to the reader.

Table 1.1 Performance of Disabled Readers in Top-Down Areas

Table 1.2 Performance of Disabled Readers in Bottom-Up Areas

Reading: Top-Down Processing

Areas in Which the Reading-Disabled Perform as Well as Normals

High Confidence: Use of Context to Speed Word Recognition. (See Table 1.1) According to top-down models of reading, people generate hypotheses about text as they read, focusing on the decoding of individual words only when the hypothesis fails to be confirmed (Goodman, 1976; Smith, 1973). According to this view, then, proficient reading is driven by higher level comprehension processes, not by lower level, bottom-up processes such as the decoding of single words. A corollary of this view is that poor readers fail to make use of context, which is a higher level, comprehension-based skill, to aid in word recognition. However, the lack of evidence to support the hypothesis-testing models has been noted elsewhere (Stanovich, 1982). Recent research indicates that disabled readers not only are capable of using context to facilitate word recognition but actually rely on context to speed decoding more than do good readers (Allington & Strange, 1977; Perfetti, 1982; Perfetti & Roth, 1980; Stanovich, 1980; Stanovich & West, 1979; Weber, 1970).

These findings do not contradict previous findings that disabled readers perform more poorly on measures of contextual sensitivity and knowledge, such as a cloze procedure or a sentence completion task. Rather, they indicate that during actual reading, good readers have no need to use context to aid decoding, because they recognize words so rapidly that the processing of other types of cues does not have time to be completed. Disabled readers, on the other hand, need to supplement their slow decoding abilities by relying on context. (We offer evidence regarding the deficient decoding abilities of disabled readers later.) Thus, it appears that good readers acquire greater knowledge regarding context, as one would expect, but they use this knowledge minimally, if at all, to speed ongoing word recognition.

Two points should be raised here. First, in order to make use of context during reading, the reader must be able to recognize some minimal number of words in the text; otherwise, there is no inferred “context” of which to make use. The youngest or most severely disabled readers may therefore fail to show a context effect, especially if the reading materials are too difficult for them. Second, we should acknowledge that many of the researchers who have found context effects in disabled readers have used readers who were only moderately impaired. However, there is no evidence to suggest that these findings would not apply to more severely impaired readers.

Areas of Deficit for Disabled Readers

High Confidence: Reading Comprehension. (See Table 1.1.) Even when reading material that they can decode accurately, disabled readers frequently show reading comprehension deficits (Cromer, 1970; Levin, 1973; Oaken, Wiener, & Cromer, 1971; Smiley, Oakley, Worthen, Campione, & Brown, 1977). Vellutino (1979) has presented convincing evidence that these deficits are not attributable to poorer general language comprehension, provided IQ is controlled, as in the study by Oaken et al. (1971). Instead, the reading comprehension problems of disabled readers may be partially accounted for by their differential use of strategies during reading. For instance, Wong (1982) had reading-disabled, normal, and gifted children read a series of “story units” and select 12 units to serve as potential retrieval cues. The reading-disabled youngsters were less thorough in considering the cues and showed less tendency to check their selections. Other evidence suggests that disabled readers are less efficient at scanning text (Garner & Reis, 1981), more passive in their approach to reading (Bransford, Stein, & Vye, 1982), less likely to use elaborative encoding to aid comprehension (Pearson & Camperell, 1981), and less able to adjust their reading strategies to suit varying purposes for reading (Forrest & Waller, 1979).

However, the relationship between strategy use and reading disability is not as straightforward as it might initially appear. For one thing, it is important to distinguish between knowledge about a given strategy and spontaneous use of that strategy in a particular situation. Disabled readers may have knowledge about a strategy, yet may still fail to employ the strategy on their own, perhaps beca...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of Contributors

- Foreword

- Part I: Microlevel Cognitive Aspects of Learning Disabilities

- Part II: Macrolevel Cognitive Aspects of Learning Disabilities

- Part III: Socioemotional Aspects of Learning Disabilities

- Part IV: Neuropsychological Aspects of Learning Disabilities

- Author Index

- Subject Index