- 234 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A History of the Polish Americans

About this book

In the last, rootless decade families, neighborhoods, and communities have disintegrated in the face of gripping social, economic, and technological changes. Th is process has had mixed results. On the positive side, it has produced a mobile, volatile, and dynamic society in the United States that is perhaps more open, just, and creative than ever before. On the negative side, it has dissolved the glue that bound our society together and has destroyed many of the myths, symbols, values, and beliefs that provided social direction and purpose. In A History of the Polish Americans, John J. Bukowczyk provides a thorough account of the Polish experience in America and how some cultural bonds loosened, as well as the ways in which others persisted.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access A History of the Polish Americans by John.J. Bukowczyk in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Ethnic Studies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

FROM HUNGER, “FOR BREAD”

Rural Poland in the Throes of Change

While in Zbaraz [Galicia] I visited a school for peasant children. Its sessions were held in a rustic little one-room building with the conventional thatched roof…. [F]or my especial benefit, the prize scholar was asked where was America. He hesitated a moment, then he said he did not know, except that it was the country to which good Polish boys went when they died….

Louis E. Van Norman, Poland the Knight Among Nations (1907)

The history of Polish America begins abroad, for it is the story not only of why Polish men and women came to the United States but why they left their Polish homes. Rural Poland was a turbulent place in the nineteenth century, when large numbers of Poles first began to emigrate, looking for work and “for bread.” But the turbulence in Polish rural society that produced the mass migrations did not begin in that period. It had its roots in the preceding three hundred years of Polish history, stretching back to the 15005.

For Poland, the 15008 were a “golden century/” The largest and perhaps the most powerful state in Europe, Poland was the “knight among nations” in western Christendom during those luminous years and stood as the eastern bulwark against tsarist, Tartar, and Turkish incursions.1 Poland’s position, however, was fragile, its power ephemeral. Repeatedly invaded by Sweden in the mid-1600s—a period aptly termed “the Deluge”—the Polish state had entered a period of irreversible decline that lasted through the next two centuries.

The causes of Poland’s decline were complex. Faced with the rise of strong, centralized states on all sides—the Russian Empire in the east, Brandenburg-Prussia in the north and west, and the Austrian Empire ringing its southern border—the Polish state, which encompassed the Duchy of Lithuania and the Ruthenian borderlands, also suffered from internal weaknesses that exacerbated its dangerous international situation. Like western European countries, Poland experienced not only the Protestant Reformation, but also a highly successful Roman Catholic Counter-Reformation, events that rent the fabric of Polish society. Ethnically, the expansive Polish state was seriously divided. The perennial succession crises that followed the deaths of Poland’s elected monarchs produced chronic political instability in the Polish state and quixotic vacillations in policy.

The political instability that plagued Poland was symptomatic of a fundamental internal problem: decentralization of power. Poland’s aristocratic families held a tight grip on their domains and jealously guarded their rights and privileges against infringement by would-be absolute monarchs. The source of the nobility’s power was control over the land. Polish aristocrats derived status and wealth from their vast landed estates, which gave them sweeping political influence at the expense of the monarchy and the state. The central position of landed property in Polish society, however, produced two additional detrimental effects. First, social status in Poland was equated with dominion over the land which deterred Polish nobles from engaging in commercial pursuits. This depressed the development of manufacturing and trade in Poland precisely when such enterprise was becoming the backbone of Europe’s modern, centralized states. The largely neglected nonagricultural sphere in Poland therefore devolved on the country’s ethnic minorities—Germans, Gypsies, and Jews—whose efforts were rewarded with low social status. Second, the Polish nobility monopolized the country’s forests and agricultural lands. These were operated through the institution of serfdom, which doomed Poland’s peasantry to permanent deprivation and exclusion from the political life of the nation. Amidst aristocratic splendor, the condition of Poland’s serfs was bleak. The questions of the peasants and land reform would remain perpetual sources of trouble for Poland.

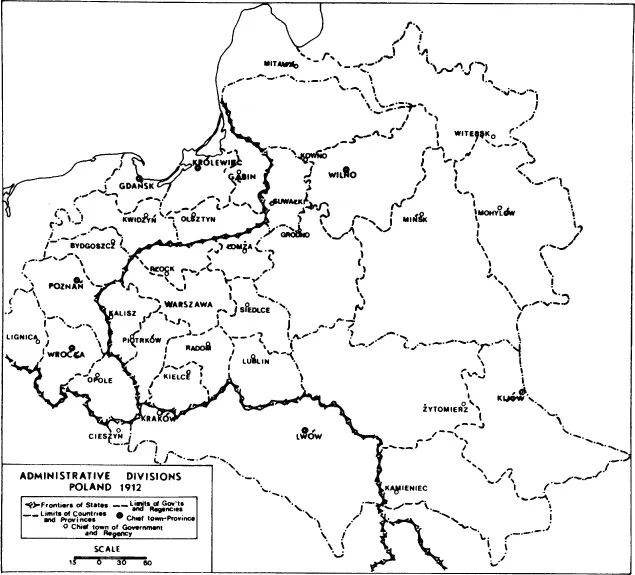

Poland entered the eighteenth century after a period of decline that sometimes bordered on chaos. Its population decimated by the warfare of the preceding hundred years, by the mid-1700s the exhausted Polish state appeared defenseless to her acquisitive neighbors. The country now faced dismemberment. Undermined by domestic intrigues at the hands of leading Polish families who were more interested in protecting their own interests—as individuals and as a class—than those of the nation, in 1772 Poland was forcibly reduced in size by its rapacious neighbors, Russia, Prussia, and Austria. This First Partition delivered Poland’s West Prussian territory to Prussia, lopped off the eastern tier of Polish provinces for Russia, and bestowed Galicia, in the south, on the Austrians. The partition of Poland was not destined to end with these modest annexations, however. Polish liberals, under French Revolutionary influence, promulgated the reformist Constitution of the Third of May in 1791; Russia and Prussia leapt to quell what they perceived as nascent Polish Jacobinism. The Second Partition, which was imposed in 1793,^e^ Poland territorially unviable. An insurrection in 1794, led by Tadeusz Kosciuszko, briefly challenged the will of the three dominating empires, but was brutally suppressed. In 1795 a Third Partition divided up what was left of the Polish state, and, as a result, Poland disappeared from the map of Europe. During the Napoleonic years a Duchy of Poland was briefly formed only to be dissolved by the victorious Holy Alliance of the three empires. In 1815 the empires once again tightened their hold on Poland through what became, in effect, a fourth partition: Prussia and Austria acquired no new territory, and Cracow fell under tripartite jurisdiction (a status that lasted from 1815 to 1846, after which time it became the capital of Austrian-held Galicia), and Russia gained control of the lion’s share of Poland. Lithuania was permanently severed from Poland and reconstituted as a separately governed territory under Russian tutelege,while the vast stretches of central and eastern Poland were organized into the Congress Kingdom (named after the Congress of Vienna), also under tsarist stewardship. (See Maps 1 and 2.)

Map 1. Partitioned Poland, circa 1870.

Reprinted from E. Kantowicz, Polish-American Politics in Chicago, 1888–1940 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1975), p. 4. © 1975 by The University of Chicago.

Map 2. Administrative Divisions of Poland, 1912.

From Caroline Golab, Immigrant Destinations (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1977), p. 76, reprinted by permission of the author.

Patriotic segments of the Polish aristocracy and middle class did not rest easily after Poland’s bitter losses. The history of nineteenth-century Poland is remembered for a succession of uprisings that vainly sought to throw off the yoke of foreign oppression. In November 1830, Polesin the Russian partition rebelled against the tsar but were quashed ten months later. An 1846 uprising by Polish aristocrats was suppressed by the Austrian government with the assistance of the peasants, who harbored bitter grievances against their Polish landlords. Two years later, in 1848, an insurrection took place in the Prussian-held territory of Poznania. One result of Europe’s “Springtime of Nations,” the Prussian Polish uprising, was crushed also. The last armed insurrection in Poland took place in January 1863, in the Russian-held Congress Kingdom. By 1865, however, the January Insurrection was spent.

In terms of altering Poland’s divided and subject status, this series of uprisings was an abysmal failure. Yet the insurrections underscored one fact expressed in the Polish national anthem, popularized during the Napoleonic period: “Poland is still living while we are still alive.”2 The November Insurrection of 1830, in particular, produced the core of Polish romantic nationalist ideology. Gifted writers and poets such as Adam Mickiewicz, Julius Słowacki, Sigismund Krasinski, and August Cieszkowski were all inspired by the uprising. Mickiewicz and Słowacki were instrumental in creating the new doctrine, which came to be known as Polish Messianism. A mystical doctrine, it claimed that Poland was a martyred Christ figure, crucified by the partitioning powers. Unlike Christ, Poland suffered for real sins, but like Him, a resurrected Poland would one day bring universal redemption to the nations of the world. Polish Messianism burned brightly in the hearts of a generation of Polish patriots sacrificed on the altar of insurrectionary politics.

After the failure of the January Insurrection of 1863, political temperaments moderated as more and more Poles accepted the partitions, and influential Poles sought an accommodation with their overlords. Polish positivists coined a new political slogan, “organic work,” which sought to strengthen their country not through force of arms but through education, work, and industry. At the same time, they sought to make the best of a bad situation by advancing their own private economic and political interests.

Into the eighteenth century, the two points of relative stability in Polish society were the institution of serfdom and the manorial system from which Poland’s estate-holding families derived their power. Serfdom in Poland developed only between the fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, when that country became Europe’s granary (serfdom was established earlier in western Europe). Once in place, however, Polish serfdom replicated many of the devices of western European feudalism—feudal dues and compulsory labor, tillage- and use-rights, peasant bondage to the land, and mutual duties and obligations between classes. More important, despite the fact that large surpluses of grain were extracted from peasant serfs and funneled into the international cereals exchange, peasant households in much of Poland remained shielded from the market economy. Into the eighteenth century, Polish rural society was, in short, insular and static. This would change with the breakdown of serfdom and the collapse of the manorial world that it supported.

In the late eighteenth and the nineteenth century a veritable revolution was taking place in Poland’s social and economic systems. In the nineteenth century, Polish rural society became a cauldron of social and economic change in which a population increase, the expansion of commercial agriculture, and the growth of transportation, industry, and urban markets would forever disrupt the manorial world. The dissolution of the ties that bound the rural populace to the land and the creation of a large pool of surplus labor would later impel the mass migrations of the late nineteenth and the early twentieth century. How did these changes occur?

Divided into separately administered partitions, the lands of Poland experienced growth of population and commerce not simultaneously, but in sequence. These developments were affected by the separate experiences of the three partitioned areas and were influenced by the varying policies of the partitioning powers. Thus, the history of nineteenth-century rural Poland is not a single history at all, but three distinct histories.

The sweeping changes that transformed Polish rural society in the nineteenth century first occurred in the German-held* lands of western Poland. The Regulation Reform of the Napoleonic era ended serfdom there between 1807 and 1823, but left the majority of the peasants landless, stripped of their former feudal rights, and burdened by a system of taxes established to compensate their former masters. A thin stratum of well-to-do peasants did manage to fare reasonably well despite the meager terms of the emancipation, but the large landholders, or Junkers, still retained control over most of the land.

In the aftermath of emancipation, German Poland experienced a radical polarization of classes. The Junkers bought out the small holdings of an indebted and increasingly hard-pressed peasantry and consolidated their already large estates into vast commercial farms. By the latter part of the century, this powerful class monopolized about half of the best land in the German-held territories of Poznania and Pomerania. The other classes in German Polish rural society were less successful. Well-to-do peasants still survived as an important social group. The swelling ranks of landless agricultural laborers, who were systematically impoverished in the decades following emancipation, formed the new rural proletariat, which became an increasingly important element in German Polish rural society. By 1880, fully 80 percent of the rural populace in Poznania and Pomerania fell into this distressed category.

Large landowners were supported by the German government in their efforts to transform the rural economy into a system of largescale commercial agriculture. The policy of Poland’s German overlords encouraged the development of commercial agriculture and actively sought to make German Poland into “Germany’s granary.”3 The state kept taxes on the great estates low and erected a banking and credit system that helped finance commercial agriculture. It also established a system of subsidies that protected German Polish landowners from competition by American wheat producers. Government policy also encouraged agricultural improvement in German Poland. The scientific farming techniques that were introduced—such as the use of improved seed and mineral fertilizers, crop rotation, and the diversification of crops, which saw the substitution of cattle and clover for grain cultivation—caused German Polish agricultural productivity to skyrocket. It also rendered superfluous the labor of increasing numbers of German Polish agricultural laborers. Mechanization of agriculture in the 1880s enhanced this harsh effect.

Higher productivity in German Polish agriculture might have led some to pronounce the commercial program a stunning success, but it produced staggering social costs. Emancipation of the German Polish peasantry was accompanied by widespread evictions, the expansion and consolidation of large estates created a vast pool of landless agricultural laborers, and the scientific revolution in farming techniques, which increased efficiency, exacerbated rural unemployment. For inhabitants of the countryside, the net effect was at best disruptive, at worst disastrous. Literally pushed off the land, German Poles entered other trades but found opportunities for employment severely limited. Bismarck’s Kulturkampf in the 1870s, which was an attempt to erase Polish culture, and, in the subsequent decade, the colonization of German settlers on the German-held lands, further constrained the Poles. For Poles with some resources, however, one avenue of escape remained—emigration.

While the partition of Poland served to stimulate commercial agricultural development in the German-held territories, in Austrian Poland the partition resulted in economic stagnation. Partition boundaries interrupted river traffic on the Vistula, blocking Galicia from its western European grain markets. With no accessible market, the development of commercial agriculture was arrested. Galicia remained poor and very backward. Outmoded agricultural techniques continued, such as burning manure for fuel instead of using it as fertilizer, and the inefficient, three-field crop rotation system, which was practiced into the late-nineteenth century. Maldistribution of land—the prevalence of large estates—underlay the nagging poverty of rural Galicia and caused sharp class antagonisms. In addition, Galicia’s population of Poles, Ukrainians, Moslems, and Jews generated ethnic and religious tensions.

In 1848, the Austrian government abolished serfdom in its Polish province, but emancipation brought little improvement to the mass of the peasantry. Under the terms of emancipation, the Austrian government forbade peasant evictions, endowed emancipated peasants with strong tillage- and use-rights, and allowed partible inheritance without setting a legal limit below which a farm could not be divided. This was done mainly to exacerbate class tensions between peasants and large landowners, rather than to protect the Galician poor. For the rest of the century struggle would continue between peasants and landowners over control of the soil and use of the rich forest lands. By driving a wedge between the Polish peasantry and their Polish landlords, Galicia’s Austrian rulers cleverly sought to forestall the development of a broadly based Polish nationalist movement.

The political effects of Austrian policy were as predicted, but its social and economic results came as a grim surprise. If the policy of the German state had proved disastrous for the inhabitants of the German Polish countryside, Austrian policy in rural Galicia was catastrophic. Many Galician peasants acquired fewer than four acres as a result of emancipation, far too little for subsistence farming. These small land-holdings, moreover, consisted of widely scattered plots “so small, as the saying ran, when a dog lay on a peasant’s ground, the dog’s tail would protrude on the neighbor’s holdings.”4 They were inefficient because of size, shape, and difficulty of access. The Galician nobility continued to hold 43 percent of the arable land and fully 90 percent of the forests, and extracted a thirty-year land tax from the oppressed peasantry in order to compensate themselves for emancipation. This pattern would change little by the century’s end.

In 1866, rapprochement between the Galician Polish landlords and the Austrian government delivered a large degree of local autonomy to the landowners. They used this newly won political influence to tighten the screws on the peasantry. By 1900, Galician statistics were truly depressing. In that year, the nobility held 37 percent of the arable land; forty-five estates consisted of over 15,000 acres each. Among the rest of Galicia’s rural society, a pattern of small holdings obtained: 84 percent of peasant holdings were smaller than 12.2 acres; 48 percent were smaller than 5 acres; 700,000 peasants were completely landless; and a mere 5 percent of the peasant population achieved self-sufficiency. For good reason people coined the term “Galician misery.”

As miserable as the Galician peasantry may have been because of the inequitable landholding system, other factors made their situation worse. Illiteracy and alcoholism were rife throughout Austrian Poland, while disease was a veritable scourge. Between 1847 and 1849 a typhus epidemic claimed 400,000 lives, while cholera killed over 100,000 between 1852 and 1855, 35,000 in 1866, and 120,000 between 1872 and 1877. Hunger also afflicted the province. Like Ireland, Galicia was hit by a potato blight between 1847 and 1849, and 1855 became tellingly known a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Maps

- Introduction

- Preface

- 1. From Hunger, “for Bread”

- 2. To Field, Mine, and Factory

- 3. Hands Clasped, Fists Clenched

- 4. Continuity and Change in the 1920s and 1930s

- 5. The Decline of the Urban Ethnic Enclave

- 6. What Is a Polish-American?

- 7. Vanguard or Rearguard?

- Epilogue

- Bibliographical Essay

- Notes

- Index