![]()

Chapter 1

INTRODUCTION

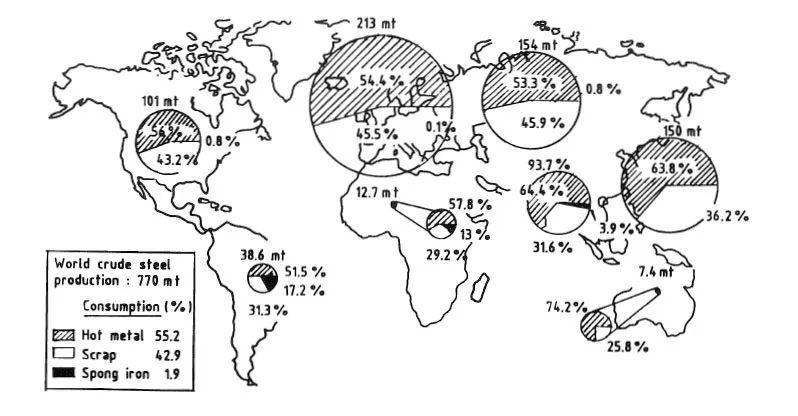

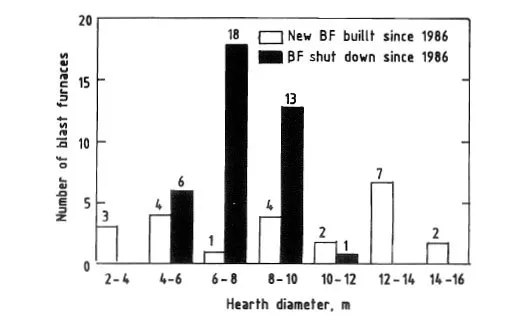

The classical blast furnace is still the principal means of hot metal production. In fact, over 95% of the total iron in the world today is produced using this process, as was the case a century ago. Figure 1.1 presents the percentage contribution of hot metal in steelmaking across the globe in 1990.1 Such a long and sustained track record of blast furnaces arises out of the continuous developments in design, such as increases in capacity; alterations in profile; improved burden distribution systems like movable throat armor and Paul Wurth (PW) top; high top pressure operation, etc.. It also reflects upgrades of the process technology, such as the use of higher hot blast temperature, oxygen enrichment of the blast, auxiliary fuels including coal injection, prepared burdens, automatic measurement and control systems, and artificial intelligence systems, resulting in a significant increase in productivity, a decrease in coke rate, and an improvement in the quality of hot metal in classical blast furnaces. It is interesting to note that, in the year 1990, 527 million tons of hot metal were produced by 541 blast furnaces, which means an average production per furnace of almost 1 million tons of hot metal,1 although many of the new furnaces constructed between 1986 and 1991 were either “very large” or “very small” — the latter comprising the so-called mini blast furnaces (Figure 1.2).1

FIGURE 1.1. Percentage consumption of hot metal, scrap, and sponge iron in the world in 1990 at a charge of 1240 kg/t of crude steel.

FIGURE 1.2. Blast furnaces newly built and shut down during the period 1986 to 1991.

There are, however, certain limitations inherent in the blast furnace process. The process depends on metallurgical coal (required for the manufacture of blast furnace grade coke), it is an economically viable process only when it produces relatively large quantities (around 2 million tons per annum, or mtpa), and it requires elaborate supporting facilities such as raw materials handling and preparation systems, a sinter plant, coke ovens, a gas cleaning system, etc. These factors make the conventional blast furnace highly capital-intensive and often beyond the reach of smaller manufacturing units.

Since blast furnace ironmaking is carried out in a single reactor, intrinsically different unit operations, like counter current heat and mass exchange, reduction by gases, reduction by solid carbon, high temperature gas generation, and finally, smelting and liquid drainage, all occur together. This means that the only way of ascertaining the efficiencies of the individual processes occurring within the blast furnace, which is a semicontinuous reactor, are periodic analysis of hot metal and slag and continuous gas analysis using a variety of probes, even within the burden in some cases. Although attempts have been made recently to introduce these probes, particularly in the furnace stack area, when corrective measures have been taken to alter the process parameters based on the data gathered from such probes, the responses to these measures could only be assessed after several hours. Therefore, the blast furnace is a reactor with a certain amount of mystique attached to it, and though this may lend it a romantic air of mystery, it does not make it a controlled reactor with high productivity and “hit rate”.

The limitations imposed by concurrent reduction and smelting in a blast furnace have led to renewed interest in alternative forms of ironmaking which can be more readily linked to fast, high-productivity steelmaking processes. These alternatives include direct reduction (DR), smelting reduction (SR), iron carbide manufacture, and of late the so-called mini blast furnaces (MBFs), which really do not constitute an alternative system in the classical sense but form an extension of normal blast furnace ironmaking into the hitherto uncharted territory of small scale operation. It must be mentioned at this stage, to provide perspective, that while the blast furnace process is fully established, many of the alternative systems still exist only on paper, and to this extent it is difficult to make direct comparisons of the broad process systems.

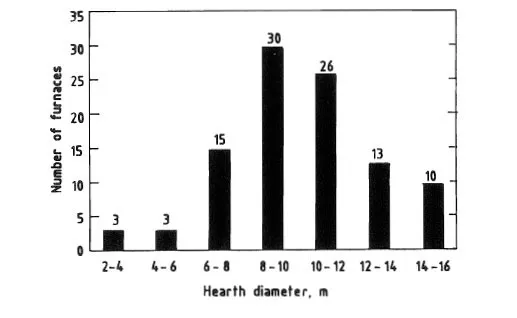

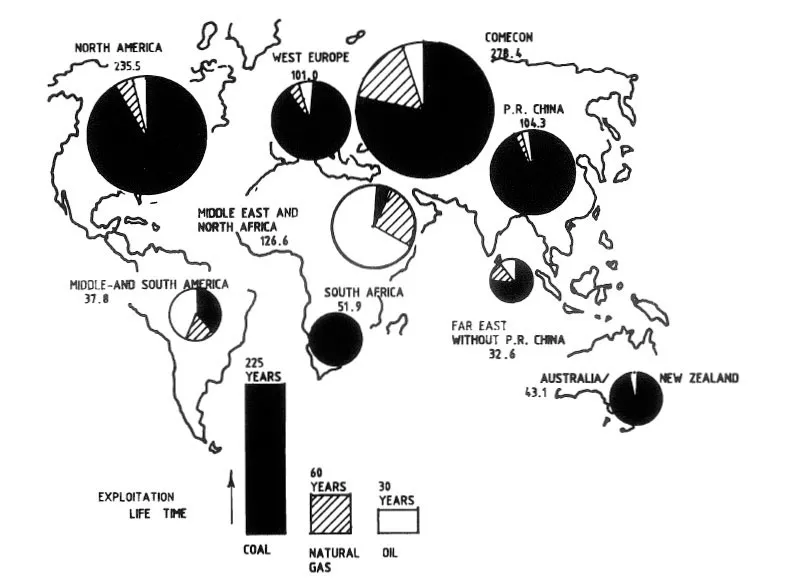

Because all metallurgical reduction processes occur at high temperatures, they consume substantial amounts of energy. In the blast furnace process, the energy is supplied by the hot blast, the combustion of coke, and increasingly, as shown in Figure 1.3, by direct coal injection through the tuyeres.1 All the alternative processes aim to eliminate or reduce the energy supply via coke. Thus, for an appreciation of alternative processes, it is necessary to take stock of the available energy resources of the world.2 As shown in Figure 1.4, coal represents the largest reservoir of energy still available to mankind. As a result of the continually dwindling reserves of oil and gas, coal is expected to meet an increasing share of metallurgical energy requirements in future. Furthermore, oil and gas reserves are concentrated only in some regions, whereas coal is more evenly distributed world wide. At the current rate of usage, it is estimated that the resource life of natural gas would be around 60 years, of oil only 33 years, and of coal 225 years. Oil and natural gas should, therefore, be used for the production of high value products, as far as possible, and coal should form the basis of all the alternative ironmaking processes that stretch “beyond” the blast furnace.

FIGURE 1.3. Blast furnaces of different size operated with coal injection in the world (as of November 1991).

FIGURE 1.4. Available energy resources in the world.

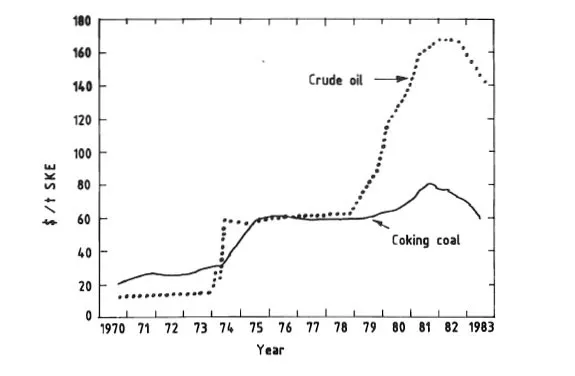

Furthermore, it should be understood that energy accounts for about 20 to 25% of total manufacturing costs in steelmaking, and 65% of this cost is for the coal and coke consumed at the ironmaking stage. The contributions from fuel oil, natural gas, and electric power have risen gradually during the last two decades, but of late, the accent is again back on coal primarily because of the comparative world prices and relative availabilities of these forms of energy. Figure 1.5 clearly illustrates how the global market price of coal has changed only slightly since 1978–1979 compared with crude oil, which experienced major price swings even as late as 1991. It can thus be stated with some degree of certainty that in the long run, coal will continue to be less expensive and its price will certainly be more stable than that of the other forms of energy. Use of coal and similar solid reductants has therefore increased in the new technologies being developed and adopted in the iron and steel industry all over the world. In some areas, where natural gas is abundant, it automatically becomes the preferred source of energy, but such cases are infrequent compared with the use of coal.

FIGURE 1.5. Fluctuations in the prices of crude oil and coking coal in the world.

Vagaries in the scrap market and an anticipated shortfall in its supply in the coming years have given impetus to the development of DR processes for the production of sponge iron and of the upcoming technique of using natural gas (or coal gas) for the manufacture of another scrap substitute, iron carbide. Production of steel using Direct Reduction-Electric Arc Furnaces (DR-EAF) has now become a firmly established process which is being adopted increasingly all over the world.3 Sponge iron, or direct reduced iron (DRI) as it is also often called, has also been used in many other steelmaking processes, including oxygen steelmaking, which is by far the predominant means of producing steel. The past 10 years have thus witnessed major structural changes in the steel industry — an increase in essentially solid charge-based steelmaking (e.g., the Electric Arc Furnace and the recent Energy Optimization Furnace) and the overwhelming popularity of continuous casting being two key factors. At the same time, paradoxically, a major problem facing the steel industry all over the world, including the developing countries, has been inadequate availability of high quality scrap. This has been accentuated by the ever-increasing adoption of continuous casting. While the technology for making quality steels requires large quantities of prime quality scrap, continuous casting improves energy utilization and reduces the generation of in-plant scrap. To overcome this problem, DR process technology, based either on coal or natural gas, has come of age, which has led to the increasing use of DRI — a term which will also be used in this book to denote sponge iron — in steelmaking.

While the DR industry has reached the “adolescent” stage for supplying solid metallics, SR is a “newborn”; as it endeavors to become a complementary source of liquid hot metal and iron carbide (a source of iron units in the solid form), it is still in the “embryonic” stage.

The focus of interest in liquid iron production has always been on improving the efficiency and lowering the cost of production. Keeping the inherent limitations of the conventional blast furnace in mind, a unique set of criteria has been formulated,4 which should be fulfilled by any smelting reduction process if it is to be a serious alternative to the blast furnace for producing hot metal in small tonnages. These include:

• Use of fine ore concentrates or powdered iron ore directly, without any prior agglomeration,

• Use of less expensive fuels, like coal, lignite, etc., without coking,

• No physical or chemical limitations either on the reductant or on the iron oxide feed,

• Full control of the raw material feed and ease of removal of the end product, as well as of the outgoing gases,

• A completely stirred system with immediate response to changes in process parameters,

• Productivity index (t/m3 of reactor volume per unit time) at least five times that of the blast furnace,

• Low investment cost per unit of iron produced at a smaller scale of operation,

• Ability to meet the more stringent environmental standards which have been formulated in recent years and are the forerunners of even stricter regulations to follow in future.

Both SR processes and MBFs can fulfill many of these stipulations. In developing countries like India and Brazil, which not only have limited capital availability and limited demand for steel products but which are also deficient in suitable grades of coking coal for use in blast furnaces, MBFs are required to augment conventional ironmaking, including iron produced through SR processes in the future.

The blast furnace will no doubt continue to contribute the lion’s share to the steelmaking capacity of large integrated steel plants, even in the foreseeable future, but the use of small units is bound to mushroom, especially in catering to local ...