![]()

EXTERNAL LOADBEARING WALLS

EARLY BRICKWORK

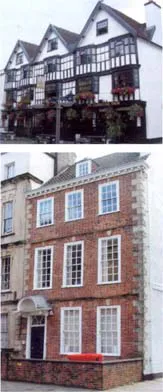

By the early 1700s brick buildings had become common in many parts of the UK. In towns and, to a lesser extent, in rural areas the timber frame tradition was slowly coming to an end. Timber (homegrown) was in short supply; there were concerns about the risk of fire, and the fashion for classical buildings did not suit the rustic, organic and irregular nature of timber framing.

These two buildings were built only 40 years apart; the one top left (1670s) is timber framed; the one bottom left is an example of the Queen Anne style (about 1710).

During the 1700s there were a number of improvements in brick making. Blended clays, better moulding techniques and more even firing gave greater consistency in brick shape and size. Fashion dictated brick colour: the reds and purples popular in the late 1600s gave way to softer brown colours in the 1730s. By 1800 the production of yellow London stocks provided a brick colour not that different from some natural stones.

The repeal of the brick tax in 1850 gave the brick industry a new impetus. Improved mixing and moulding machines, together with better firing techniques, allowed brick production to reach new heights. Bricks were now available in a range of colours, shapes and strengths that would have been unimaginable a 100 years earlier. Better quarrying techniques allowed extraction of the deeper clays, which produce very strong, dense bricks; vital for civil engineering works such as canals, viaducts sewers and bridges.

BRICK BONDING

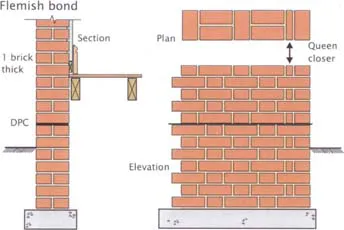

To guarantee effective weather protection and provide adequate strength the walls of houses need to be at least 215mm thick – these are known as 1 brick thick walls. Houses over three storeys often had thicker walls, usually reducing in thickness at each floor level.

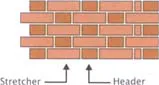

The brickwork itself was generally laid to a very high standard. Most houses were built in Flemish bond although Header bond was also popular in the early to mid 1800s. The next page shows the construction of a wall in Flemish bond. Note that all solid wall bonds require the use of special bricks, known as Queen (& King) closers to complete the bond at window openings and comers. English bond (the strongest bond) was generally reserved for engineering works although its weaker sibling, English Garden Wall bond, was used extensively at the rear of properties or behind renders. An example of English Garden Wall bond can be seen later (see Openings in solid walls on page 20).

Despite its name, English Garden Wall bond is not uncommon in older housing where it is often found forming the rear walls of houses (sometimes hidden by render). Its popularity lay in its cost. It is easier to lay and level stretchers and there is less waste because oversized bricks (which might have to be rejected as headers) can be accommodated by ‘stretching’ the joints.

Flemish and English bond are by no means the only bonds used in the construction of solid walls. By varying either bond slightly others can be formed.

Nearly all brick houses built before the 1920s were built in Flemish bond – or at least the walls on show to the Street were. In this bond a single course of brickwork contains alternating headers and stretchers. Most two and three-storey houses were built with walls 1 brick thick (see above example). Houses of more than three storeys usually had thicker walls. Flemish bond can easily be adapted to suit walls of 1.5 brick thick and 2 brick thick.

Header bond is fairly rare but it is an alternative to Flemish bond.

In Flemish bond it was not uncommon to find headers and stretchers in different colours.

MORTAR

Mortar is a mixture of materials for jointing masonry units. It has numerous tasks. It sticks the bricks together to provide stability and solidity – while holding them apart to spread loads evenly. It compensates for irregularity between units when straight, level and plumb walling is laid. It also seals any gaps to resist wind or rain penetration. As well as fulfilling its gap-filling adhesive function, it should also have adequate durability and strength.

Material for mortar

Lime mortars were common until the 1930s and are still used today, particularly in conservation work. Limestone or chalk is burnt with coal (calcination) to form calcium cxide – Quicklime. During burning carbon dioxide is ‘burnt off’. The burnt lime is known as lump lime. The next stage is known as slaking. In this process the quicklime is added to water where a vigorous chemical reaction (which produces great heat) converts the quicklime into slaked lime. Slaked lime is calcium hydroxide. The slaked lime is mixed with fine aggregates (nowadays sand) to form mortars, renders and plasters. As the material slowly sets it combines with carbon dioxide in the atmosphere to return to is original state – calcium carbonate. It can take many months for a lime plaster to fully set – hence the long delay before decorations common 50 years ago. This whole process is sometimes referred to as the triangle of lime. Slaked lime can be stored almost indefinitely.

Some limes have a hydraulic set (usually in addition to, not in place of, carbonation). This can be induced by adding pozzolans – which contain silica. There are a number of materials and industrial wastes, which can act as pozzolans. Another option is to use a lime that naturally contains silicas (usually a proportion of clay). Hydraulic sets are quicker and stronger than carbonation. Some of the very strong hydraulic limes are not dissimilar to cement (made of course, from chalk and clay). By the end of the Victorian period and during the early part...