eBook - ePub

The Rise and Fall of Philanthropy in East Africa

The Asian Contribution

- 261 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Rise and Fall of Philanthropy in East Africa

The Asian Contribution

About this book

Robert G. Gregory challenges the apparent assumption that non-Western peoples lack a significant indigenous philanthropic culture. Focusing on the large South Asian community in East Africa, he relates how, over a century, they built a philanthropic culture of great magnitude, and how it finally collapsed under the ascendency of increasing state regulation and policies directed against non-African communities.Compelled by poverty to seek better oppurtunities overseas, most Asians arrived in East Africa as peasant farmers. Denied access to productive land and sensing economic opportunity, they turned to business. Despite severe forms of racial discrimination in the colonial society, they suffered few restrictions on their business enterprises and some became very wealthy. Gregory's historical analysis shows philanthropy as an important contribution, one that stemmed from deep roots in Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist culture. The sense of nonracial social responsibility cultivated social, medical, and educational facilities designed for all.This age of philanthropy terminated with the Asian exodus. The socialist and racial policies adopted by East African governments over the past few decades have virtually destroyed the foundation necessary for philanthropy as well as the distinct Asian cultural identity. Gregory's account of the East Asian's role in philanthropy deserves great attention and sober reflection.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Rise and Fall of Philanthropy in East Africa by Robert G. Gregory,Howard Schwartz in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Settlement in East Africa

Wealth imposes obligations.

—Sir Yusufali A. Karimjee Jeevanjee, ca. 1950

East Africa offered a unique opportunity for the elaboration and application of the philanthropic traditions and practices developed in India. By the Heligoland Treaty of 1890 the eight hundred miles of the African coast extending from the mainland opposite Lamu Island in the north to Cape Delgado in the south were divided into British and German spheres of influence. The two European powers then proceeded to annex the offshore islands and the mainland interior from the coast to the great lakes. This area of approximately 675,000 square miles—nearly half the size of India and Pakistan and seven times that of the United Kingdom—they divided into the British East Africa, Uganda, and Zanzibar protectorates, and the German East Africa Protectorate. After World War I Britain acquired German East Africa as a mandate, renaming it Tanganyika, and in recognition of the growing importance of European settlement, it also changed the name of its East Africa Protectorate to Kenya Colony. These four British dependencies, henceforth known collectively as British East Africa, became the area of concentration for the last great wave of migration from South Asia.

The Migration to East Africa

Nearly all the Asians came from northwest India, where monsoon winds had fostered an age-old trade with East Africa. The indentured servants, who, beginning in 1895, were recruited to construct the Uganda Railway and other public works, were mainly from the Punjab and Sind. Most of the free immigrants came from the Gujarat, Kathiawar (Saurashtra), Kutch, and Mahrashtra; some also emigrated from Portuguese Goa. These peoples became mainly the shopkeepers and civil servants of East Africa. In the earlier years most of the migrants came from villages where they were engaged in agriculture. Later increasing numbers came from the towns and cities, mainly the port cities such as Bombay, Karachi, Broach, Surat, and Porbandar, but also from inland centers such as Ahmedabad, Baroda, Rajkot, and Poona. These Asians from cities and towns were mainly shopkeepers and professionals, but most of them had only recently left a farming occupation in the rural areas.

Life was difficult in northwest India. The Punjab, the land of five rivers where most of the indentured laborers were recruited, was fertile and well watered but overpopulated, and many small farmers had not sufficient land to sustain their families. Sind was a desert in which any livelihood was difficult to earn. The Gujarat, Kathiawar, Kutch, and Mahrashtra were fairly fertile but dependent on the summer monsoons for rainfall. In time of plentiful rain these lands could be green and luxurious. When the monsoons failed, they were dust bowls. Drought and famine, recurring every two or three years, kept the population density to half that of the Punjab.1 Goa was a verdant, tropical paradise in all but employment opportunity. The Portuguese monopolized the higher positions in the civil service, and there were too many qualified Goans for the remainder.

Poverty was compounded by overpopulation. During the century before 1850 the population of India had remained fairly constant at approximately 130 million. During the latter half of the nineteenth century, coincidental with the opening of East Africa, a dramatic growth began. Because of modern medicine, sanitation, and transportation, the death rate from disease and famine declined markedly, and the population began to grow at an annual rate of more than 2 percent. As a result, India’s population leaped from 133 million in 1847 to 236 million in 1901, to 251 million in 1921, to 317 million in 1941, and to 439 million in 1961. In the Gujarat and Kathiawar the natural increase—averaging annually over 16 per 1,000 during 1941-50—was the highest in all India. The figures would have been far higher if millions of Indians had not emigrated. Much of India’s surplus population, usually at a young, productive age, poured into Burma, Ceylon, South Africa, Fiji, British Guiana, and the West Indies as well as East Africa.2

The impoverished peoples of western India endeavored in various ways to improve their situation. Many farmers supplemented their incomes by running small shops in their villages or transporting goods from one center to another. A large number of villagers sought new opportunities overseas or in India’s towns and cities. Those who moved to the urban centers encountered not only stiff competition in employment, but severe problems of housing, sanitation, and disease. During the 1880s and 1890s, extending into the early decades of the twentieth century, Bombay, Karachi, and other port cities of western India suffered from a terrible epidemic of bubonic plague.3 Those who moved directly to East Africa from the villages were soon joined by many from the urban centers. Increasingly the farmers, shopkeepers, artisans, and laborers were accompanied by a professional class. Doctors, lawyers, accountants, teachers, and engineers, after education and qualification in India or Britain, were drawn to East Africa.

The Asian migration can be divided into four chronological periods. The first, beginning at a remote time, perhaps several centuries B.C., extended to almost the end of the nineteenth century. Like the Arabs, the Asians for millennia plied the Indian Ocean in small sailing ships. Through the Persian Gulf they traded with ancient Babylon, and through the Red Sea with Egypt, Greece, Rome, Axum, and Kush. Near the end of the first century A.D., when the Periplus was written, they apparently were trading with Rhapta in the area of East Africa. The Asians left commercial agents in the places of barter, and from these initial trading posts sizeable settlements emerged. In 1497, when Vasco da Gama explored the area, there were many Asians on Zanzibar and Pemba, and along the coast in towns such as Kilwa Kivinje, Bagamoyo, Mombasa, and Malindi. During the eighteenth century, after the Portuguese decline and the end of Dutch rivalry, both Asians and Arabs expanded their trade and settlement. After 1840, when Seyyid Said moved from Oman to Zanzibar, many Asians resident in Oman followed, and during the latter half of the nineteenth century, Zanzibar flourished as the focal point of an extensive trade between the African mainland and the outside world.

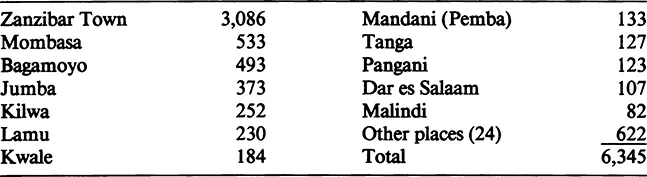

TABLE 1.1 Asian Population of East Africa, 1887

By 1890, when East Africa had been partitioned among European powers and the old period of Arab ascendency was at an end, the Asians were the dominant economic community on Zanzibar and along the East African coast. An economic and social pattern had already been established in which the Asians constituted the vital middle class. Through the centuries they had proved that under conditions of relatively free competition, such as those provided by the Zanzibar sultanate, they could compete successfully with Arabs, Europeans, and Africans and attain a controlling interest, often a monopoly, in finance and commerce. The decline of the slave trade and slavery, which had been a source of profit to them as well as Arabs, had not seriously affected their commercial interests. Sensing opportunity on the mainland, they began to migrate from Zanzibar and Pemba in increasing numbers. In 1887, when a detailed census was taken, approximately half the Asians were already on the coast.4

A second wave of Asian migration, much larger than the first, occurred between 1890 and 1914. Within this period the British, employing Indian troops, established a firm control over the new East Africa and Uganda protectorates.5 The Germans, also by means of military force, founded German East Africa. Both built railways to the great lakes, encouraged European settlement, and imported indentured labor from India. Between 1895 and 1914 the British imported 37,747 Asians, mainly from the Punjab, on three-year contracts to provide the labor essential for construction of the Uganda Railway and other public works. The Germans, utilizing more African labor, imported fewer than 200 Asians. Of the total indentured laborers, about 18 percent, some 7,000, elected to remain in East Africa on expiration of their contracts.6 While some continued to work on the railway or took other employment in government service, most became artisans or merchants in the many towns that sprang up behind the advancing railhead. These towns had been swelled by a far more numerous free-immigrant population from western India.

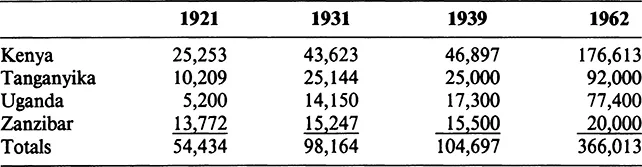

TABLE 1.2 Asian Population of East Africa, 1921-62

Between 1890 and 1921 the expanding sphere of government protection, the provision of rail transportation, and the opportunity to supply the wants of European settlers and begin a trade with the Africans attracted between 10,000 and 20,000 Asian free immigrants. Judging from immigration statistics, the Asians throughout East Africa numbered about 34,000 in 1914. By the time of the census of 1921, shown in Table 1.2, the Asian population of East Africa had risen spectacularly to more than 54,000. The East Africa Protectorate attracted by far the greatest number, but Zanzibar, which was at the height of its prosperity, had a fourfold increase.7

A third wave of migration was coterminous with the interwar period. The great influx to the British East Africa and Uganda protectorates that was interrupted by World War I resumed with the armistice in 1918 and was extended to Tanganyika with the establishment of the British administration in 1920. Unlike before 1914, the Asian population after the war grew almost entirely because of free immigration and natural increase. Although 2,024 indentured Asians entered after 1914, a total of 2,905 returned to India on expiration of their contracts. As shown in Table 1.2, the Asians of East Africa numbered 98,000 in 1931 and nearly 105,000 in 1939.8

These figures indicate that nearly all the growth occurred during the first decade after the war. Between 1921 and 1931 the total Asian population nearly doubled; during the second decade, immigration almost ceased and the population apparently grew only by natural increase. That the economic depression of the thirties had so profound an effect on Asian immigration illustrates the continuing importance of economic opportunity as a motivation. Probably the relative lack of economic reward also explains the minimal increase on Zanzibar. New immigrants from South Asia went directly to the mainland, where, at least during the twenties, the opportunities for employment in government service, crafts and construction, and commerce and banking, especially in the wholesale-retail trade serving European and African needs, appeared exceptional.

The end of the Second World War in 1945 and the conferral of independence on the East African territories during 1961 - 63 mark the final period of extensive Asian migration. A comparison of the statistics for 1939 and 1962 reveals that the Asian population increased after the war by approximately 260,000. Again Kenya, offering the greatest economic opportunity, was the most attractive territory. After 1939 the number of Asians in Kenya grew by approximately 130,000 in comparison with 67,000 for Tanganyika, 60,000 for Uganda, and less than 5,000 for Zanzibar.9

Unlike in preceding periods, about half the increase in the Asian population was due to natural causes. In Kenya during the decade ending in 1960, for example, the natural increase and that from immigration were generally the same, at 2.5 percent per annum. A continuing high birth rate of at least 30 per 1,000 and a declining death rate were partly responsible, but independence in India and prospects for independence in East Africa made immigration less attractive. Although the number coming to East Africa grew almost every year, and the Asians continued to outnumber Europeans more than three to one, the proportion between Asian arrivals and residents steadily diminished.10

The Concentration on Business

After arrival in East Africa the immigrants often went through several weeks or months of uncertainty and privation while determining their initial location and employment. Although some had a smattering of English, very few knew any German, Arabic, or Swahili. Even among Asians they were strangers outside their own communities. In most cases, with a life of poverty behind them, they had borrowed the money for the voyage or spent nearly all their savings, and rarely did one arrive with more than a few rupees in his pocket. The Goans and the Patels, fairly versed in English, could hope for some government position. The peasant farmers, such as the Shahs or Punjabis, lacked an adequate knowledge of English and had no skill in crafts or firsthand experienc...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Preface

- Introduction

- 1. The Settlement in East Africa

- 2. Asian Charitable Organizations and the Leading Benefactors

- 3. Deployment of Earnings and Savings

- 4. Creation of Religious, Social, Medical, and Library Facilities

- 5. Provision of Schools

- 6. Establishment of a Gandhi Memorial

- 7. From Royal Technical College to University of Nairobi

- 8. Literature and the Arts

- 9. Contributions to Non-Asian Peoples

- 10. Conclusion

- Bibliography

- Index