Method

The Survey Experiment. The fundamental claim of our cultural-values interpretation of social trust is that social trust is based on value similarity: people tend to trust other people and institutions that ‘tell stories’ expressing currently salient values, stories that interpret the world in the same way they do. One way to test this cultural-values hypothesis is through the use of what we call the ‘survey experiment’, a procedure in which survey-like methods and materials are used – but with a twist: The contents of the materials (questionnaires) are manipulated so that they create the structure of an experiment. Thus, different forms of a basic questionnaire are used to create cells in an experimental design.

One version of the survey experiment, employed successfully by several research groups, incorporates systematic variations in both questionnaires and respondents. Clary and colleagues (Clary, Snyder, Ridge, Miene and Haugen, 1994), for example, varied the motives expressed in messages and the motives that were personally relevant to respondents (eg knowledge, social adjustment, value expression, ego defence and utilitarian). These researchers demonstrated that matches between message and respondent motives were more persuasive than mismatches. Matches on motives also produced higher levels of trust. Similarly, Arad and Carnevale (1994) showed that partisan individuals judged the trustworthiness of a neutral third party on the basis of whether his proposal matched their position. By using a method that can accommodate variation in both experimental materials and respondents, studies like these can explore interactions between the two sets of variables. The basic assumption of these studies, and of ours, is that the effects of a message, for example, depend critically on how it is interpreted by the person reading it. In our studies, we examined the effects of the culture of individuals on their interpretations of risk messages that expressed varying sets of cultural values. Based on our cultural-values theory of social trust, we expected matches between the culture of individuals and the culture of messages to produce higher trust judgements than mismatches.

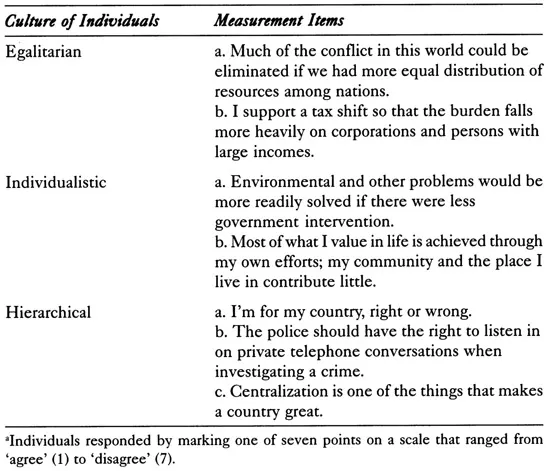

The Culture of Individuals. Our first attempt to describe and measure the culture of individual respondents was based primarily on the work of Karl Dake, who has expressed the categories (or ‘cultural biases’) of cultural theory in the form of questionnaire items (Dake and Wildavsky, 1990; Dake, 1992). There are three primary categories in cultural theory: Egalitarian, Individualistic and Hierarchical. A fourth category, Fatalism, was not included in this study. The items we used, given in Table 1.1, consisted of a mixture of those described by Dake and Wildavsky (1990) and our own. Standard statistical analyses (Jessor and Hammond, 1957; Judd, Jessor and Donovan, 1986) were used to select the items, based on data from 449 respondents.

Individual respondents were assigned scores on each of the three scales based on the mean of their responses to the items contained in a scale. Thus, each respondent had an Egalitarian score, an Individualistic score and a Hierarchical score. Respondents were classified in this way: if a respondent’s

Table 1.1 Items Used to Measure Culture of Individuals: Culture Theorya

Egalitarian score was greater than or equal to his/her Individualistic score and greater than or equal to his/her Hierarchical score and, in addition, was greater than or equal to 4 (the midpoint on the response scale), then that individual was classified as Egalitarian. Analogous procedures were used to classify respondents as Individualistic and Hierarchical. A total of 402 respondents were classified into the three cultural categories: 282 Egalitarian; 76 Individualistic; 44 Hierarchical. These individuals were unpaid volunteers recruited from both university student and general populations in western Washington State. Their average age was 28.3 years, ranging from 15 to 72. Gender distribution was even, with 50.4 per cent male, and there was no relation between gender and culture.

The Culture of Messages. The messages used in this study were written in the form of brief, simulated newspaper stories.4 Each story was composed of two parts. The first part was a core story that was read by all respondents. Since the data were collected late in 1992, a (fictional) story concerning the prospective high-level nuclear waste management policy of the incoming Clinton administration was selected as timely and moderately involving to a broad range of potential respondents. A key part of the core story stated that ‘a new decision-making procedure’ will be used. The second part of each message provided a description of that procedure in one of three forms designed to succinctly express the relevant Egalitarian, Individualistic or Hierarchical values identified in cultural theory.

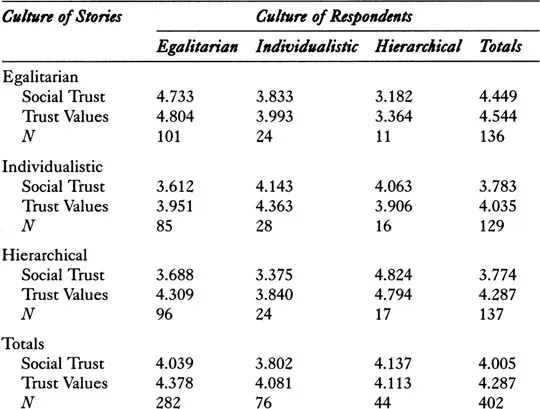

Social Trust and Trust Values. Our cultural-values interpretation of social trust claims that social trust is based on value similarity: individuals tend to trust institutions that express currently salient values. A simple test of this notion would include: a) a measure of judged value similarity; b) a trust judgement; and c) a measure of the relation between a) and b). Our measure of judged value similarity consisted, first, of the following question referring to the nuclear waste management message the respondents had read:

The proposed new federal organization described in the story is the Nuclear Waste Management Agency (NWMA). Based on what you have read here, how do you feel about the NWMA?

This question was followed by a six-item trust-values scale. Each of the six items consisted of a seven-point response scale anchored by bipolar descriptors of the relations between the story and the respondent:

Standard procedures (Jessor and Hammond, 1957; Judd, Jessor and Donovan, 1986) were used to select these items from an initial large pool. A trust-values score, consisting of the mean of the six response scales, was computed for each respondent. Our measure of social trust was a single judgement made in response to this question:

Based on what you have read here, would you say you would trust the NWMA?’

The correlation between respondents’ social trust judgements and their trust-values scores gives us a measure of the relation between the two, a simple test of our hypothesis that social trust is based on shared cultural values. In addition, of course, the social trust judgements and the trust-values scores are the dependent variables in our experimental test of this hypothesis.

Procedure. The newspaper-style stories on nuclear waste management and the questionnaire items measuring social trust, trust values and the culture of individuals were presented to respondents in the form of a booklet. The booklet contained an unrelated task in addition to the one described in this report. The nuclear waste management task appeared first in half the booklets. Order had no effects on respondents’ judgments, and it is ignored here. In the booklet, a general set of instructions dealing with the mechanics of responding to items was followed by the first task and the questionnaire items related to it; then came the second task and its items. The social trust items described in this report are a subset of the nuclear-waste-management-task items. The items used to measure respondent culture followed the two tasks, and the booklet ended with a set of questions about the respondents’ backgrounds. The booklets were randomly assigned to respondents, and the respondents worked on the booklets individually, self-paced.