eBook - ePub

Markets for Federal Water

Subsidies, Property Rights, and the Bureau of Reclamation

- 328 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This book clearly and authoritatively addresses significant issues of water policy in the western United States at a time when the growing scarcity of western water and the role of the Bureau of Reclamation in the allocation of that resource are becoming increasingly urgent issues. In this scholarly study, Wahl combines his insider's knowledge of the Interior Department's dam-building, regulatory, and water-pricing decisions with an objective analysis of the efficiency dilemma. The study begins by tracing the origins of the reclamation idea and the expansion of subsidies in the program since 1902. The author then recommends major changes in reclamation law and in the Bureau of Reclamation's policies for administering its water supply contracts. He uses four case studies to illustrate the application and potential benefits of his proposals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Markets for Federal Water by Richard W. Wahl in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

History and Evolution of Subsidies

1

History of Federal Involvement in the Reclamation Movement

Imagine what it would have been like to be an early explorer of the Colorado River region, such as John Wesley Powell. Observing the vast spaces, the deserts, and the river cutting its way from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California, what visions might you have had of its future development? How would your visions compare with those of the one-armed major who guided his wooden dory through the rapids of the inner gorge of the Grand Canyon? How would they compare with the way the land and water resources in this region are used today?

Would you envision agricultural development only within the confines of the flat grassy valleys along the Colorado River and its tributaries? Or would you picture the water supply as sufficient to be diverted on a scale vast enough to make the deserts bloom? Would you want the federal government to steer this development, or would you trust the more haphazard and piecemeal results of leaving development to local and private interests? If you perceived a federal role, would it be limited to providing information on settlement opportunities or would it extend to providing loans, grants, and even construction of irrigation works? These are the questions that became central to the early debates over "reclamation" of the arid West.

Powell's expeditions and surveys, which began in 1867 and continued with his trips down the Colorado River in 1869 and 1871, motivated him to think about a plan for the western lands. His Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States, published in 1879, embodies a set of proposals regarding irrigation. Powell's own views on these subjects changed somewhat over his lifetime, but he consistently emphasized several central points. For instance, he defined the arid West as that land receiving less than 20 inches of rainfall per year, which corresponds roughly to the lands west of the hundredth meridian (except for the areas of the Northwest with heavy rainfall). Most of this land, unlike the lands in the "subhumid" areas farther east, would need some form of irrigation to sustain settlement. Powell's scientific background allowed him and his associates to estimate river flows and to compute that, even if canals were put in place to divert and distribute the region's water, the acreage irrigated could be only a small portion of the vast space available (about 2.8 percent in Utah, for example).

From this, Powell reasoned that it was important that only the best areas be irrigated: those nearest streams, with the best soil conditions and to which water could most easily be diverted. Lands somewhat farther away should be reserved for pastureland (Powell envisioned settlements that combined irrigation and grazing). The boundaries of farm homesteads should be established not by rectilinear section lines, but in accord with the topography, so that each homestead had land fronting on the river as well as pastureland (Powell, [1879] 1962, pp. 34–36).

Powell did not believe that the selection of land for these purposes was best left to the early settlers. He believed that reservoirs on the larger streams would be advisable and was concerned that settlers would use so much land along smaller tributary streams that the acreage left to be served by the larger reservoirs would be insufficient to allow the reservoirs to pay for themselves. To ensure orderly settlement and to maximize the amount of land that could be irrigated, Powell believed that a government-sponsored survey should be launched to identify the lands capable of sustaining irrigation and to identify and retain the best reservoir sites in federal ownership. Powell's plan, typical of its time, reflected the Progressive faith in government action. In other words, Powell did not trust private development to identify the most desirable lands for irrigation and to develop them efficiently. He also feared that under private development monopoly interests would capture control of streams.

Powell believed that individual farmers would not be capable of constructing the larger reservoirs he envisioned: "Small streams can be taken out and distributed by individual enterprise, but cooperative labor or aggregated capital must be employed in taking out the larger streams" (Powell, [1879] 1962, p. 21). But he did not advocate federal construction of reservoirs (also see Davison, 1979, pp. 120–124; Stegner, 1982, pp. 350, 357, 366):

A thousand millions of money must be used; who shall furnish it? Great and many industries are to be established; who shall control them? Millions of men are to labor; who shall employ them? This is a great nation, the Government is powerful; shall it engage in this work? So dreamers may dream, and so ambition may dictate, but in the name of the men who labor I demand that the laborers shall employ themselves; that the enterprise shall be controlled by the men who have the genius to organize, and whose homes are in the lands developed, and that the money shall be furnished by the people; and I say to the Government: Hands off! Furnish the people with institutions of justice, and let them do the work for themselves.

(Powell, (1879] 1962, p. 23)

On the basis of these views and his considerable experience with western land surveys, Powell eventually obtained federal authorization for an irrigation survey. But as we shall see, his success ultimately led to the undoing of many of his ideas.

Early Controversy Surrounding the Federal Government's Role in Irrigation Development

John Wesley Powell was involved in one of four general surveys of the western lands; the others were led by Clarence King, Frank Hayden, and George Wheeler. In 1880 Congress consolidated the four surveys into the U.S. Geological Survey, and Clarence King was appointed director. Powell became director of the Bureau of Ethnology at the Smithsonian Institution and then succeeded King as director of the U.S. Geological Survey in 1881. In this latter role, he managed to increase the budget for the western surveys, but the surveys came under increasing attack from Congress. In 1886 Congress held hearings on the proper role of government in the development of western lands, at which Powell emphasized the importance of surveys—especially topographic mapping—for irrigation. Criticism surfaced of even this limited government role. For example, Representative Hilary Herbert of Alabama insisted that "interested individuals and corporations" could undertake such surveys where they were needed (see Davison, 1979, p. 60; Stegner, 1982, pp. 290–292).

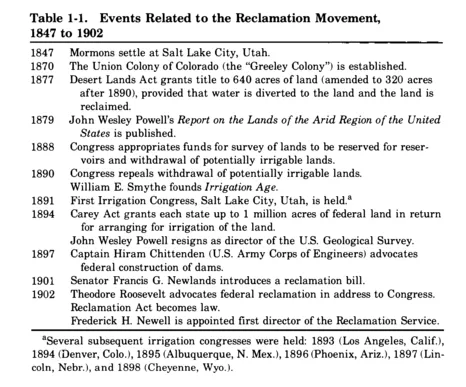

In fact, much of the settlement of the West was accomplished by private action. (Table 1-1 lists dates related to the history of the reclamation movement.) Even many of the principal irrigation developments were founded not by federal action, but by religious groups or other associations. For example, when the first group of Mormons arrived at Salt Lake Valley, Utah, in July 1847, they immediately set about diverting water to irrigation ditches and planting potatoes; by 1848 they had 5,000 acres of crops under irrigation (Golzé, 1952, p. 6).

Other western settlements that depended on irrigated farming, although not founded by an established religious institution, resulted

from a missionary zeal on the part of interested backers. In 1868 Nathan Cook Meeker, an agricultural editor for the New York Tri- bune who had written some articles on the Oneida community, was sent by Horace Greeley to Utah to study the Mormon settlements. Blocked by heavy snows, Meeker journeyed only as far as Wyoming, and then went south to Colorado. During the summer of 1869, Greeley visited him in Colorado and was favorably impressed with the land's possibilities. On December 14, 1869, the Tribune published a proposal for establishing the Union Colony on the Cache La Poudre River north of Denver and solicited settlers (see Golzé, 1952, p. 10, and Davison, 1979, pp. 136–138). Enough responded that the settlement was established during the winter of 1870–1871 and became known as the Greeley Colony. Colonies were also established in California: the Anaheim Colony was founded by Germans from San Francisco, and the Riverside Colony was founded in 1871 as a cooperative venture. All of these settlements were successful enough to lead to permanent communities.

These were private efforts, and Congress saw no need for a public role in the irrigation development of the West during most of the 1800s. The first major federal action related to irrigation development in the western states occurred in 1877 and defined only a limited federal role. In that year, the Desert Lands Act passed, which granted title to 640 acres of land (reduced to 320 acres by an 1890 amendment) at $0.25 per acre (plus a $1.00 filing fee per tract), provided that the settler diverted water to and reclaimed the land within three years. Subsequently the land could be patented at $3.00 per acre.

Further federal direction of irrigation settlement occurred when Powell's requests for federal surveys to identify irrigable lands eventually found support in Congress. In 1888 Senator William Stewart of Nevada introduced a bill that provided $100,000 to the U.S. Geological Survey for identifying "lands to be reserved for reservoirs." Some 140 reservoir sites were examined between 1888 and 1900, and 10 projects were estimated in detail (Golzé, 1952, pp. 21–23). Stewart was concerned that speculators would purchase blocks of land to be irrigated and monopolize their resale.1 The bill also called for withdrawing from homesteading the potentially irrigable lands connected with these reservoirs so that the reservoirs could be properly designed, situated, and constructed. Although Powell did not originally advocate this latter provision, he did not vigorously oppose it, probably because of his own disapproval of the practices of irrigation companies, many of which lured settlers to their lands by advertising but then failed to follow through on their claims.

As Powell's survey work progressed, he saw the result of the federal withdrawal provision: settlers were beginning to occupy the lands immediately adjacent to the lands withdrawn and to divert water to these lands. This was contrary to his own plans under which the irrigated lands would be nearest the river and the adjacent lands would be used for pasture. It became clear to him that the actual pattern of development occurring under federal withdrawals was even worse than before the withdrawals. However, rather than abandoning his plans, he advocated more government management of settlement, not less: Powell increased the size of the withdrawals of irrigable lands.

Because Powell's irrigation survey was only partially complete settlers seeking to establish homesteads were confused about precisely which lands were, or would be, withdrawn. To make matters worse, in 1889 the U.S. attorney general ruled that not only were those who settled on lands after they were surveyed and withdrawn not entitled to their lands, but also that any post-1888 homestead could be invalidated if Powell's survey subsequently indicated that the land should be withdrawn. As a result, early in 1890 the Land Office officially closed to entry nearly the entire public domain (see Golzé, 1952, pp. 21–22; Davison, 1979, pp. 92–95; Hibbard, 1924, pp. 430–431; Stegner in Powell, 1962, p. xxi; and Stegner, 1982, pp. 317–319), about 800 million acres (U.S. Department of Commerce, 1977, table 364, p. 225). With this ruling, Powell's survey was placed directly in the path of western settlement. The ensuing public uproar led to a series of congressional hearings, chaired by Senator Stewart of Nevada and held in the Midwest. As a result of these hearings, Congress in 1890 repealed the withdrawal of irrigable lands from entry but retained withdrawals of potential reservoir sites. This vote virtually ended Powell's hopes for imposing a federal plan of irrigation development on western settlement.

The hearings provided an early opportunity for the public to relay its views on western development directly to Congress and to press for federal assistance, yet the committee report concluded that no federal action was warranted beyond surveys for reservoir sites. In fact, the period from 1880 to 1890 had been something of a boom in private irrigation settlement. Companies sold stocks and bonds to finance projects in many parts of the West and lured settlers with pamphlets painting a rosy picture of farm life (Golzé, 1952, p. 11). The railroad companies also advertised to encourage western settlement (Robbins, 1976, pp. 326–327). However, dams and reservoirs were sometimes poorly built and failed to deliver the expected amount of water (there were, in fact, very few stream gauges in existence at this time that could have been used to more carefully plan water storage facilities). In some cases, settlers were enticed onto lands with heavy alkali concentrations, poor drainage, and short growing seasons (Robinson, 1979, p. 9).

Needless say, to a number of private ventures with weak foundations were overtaken by the vagaries of weather and climate and simply faded out of existence. One commentator sums up the situation as follows (Robinson, 1979):

Irrigation companies were hastily formed. Many of the large canal projects were undertaken by promoters who obtained money from east ern investors. The basis for their operation was usually a preliminary survey and a claim to the water of a stream under the appropriation doctrine. Surveys were inadequately funded and there was little interest in accuracy since someone else's money was often at risk. In nearly every instance, engineers were pressured to reduce cost estimates so as to encourage the sale of shares. Thus, in many cases projects began without sufficient capital, work was suspended before water was furnished, and the hopes and dreams of settlers depending on canals to mature crops were dashed. (p. 10)

Particularly devastating were the crop failures of the 1880s caused by low rainfall (see Robbins, 1976, p. 328), Nevertheless, a significant amount of acreage was successfully placed under irrigation. In fact, by 1890 the demand for information on irrigation development was sufficiently important that statistics were included in the census. As table 1-2 shows, 3.6 million acres were being irrigated in the seventeen western states in 1890 and double that by 1900.

It was, in fact, not from a ground swell of popular sentiment by western settlers but from a small number of irrigation enthusiasts, some of them almost fanatic, that the call for more extensive federal involvement in irrigation originated. Foremost among them was William E. ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Other Page

- Half Title

- Introduction

- Part I History and Evolution of Subsidies

- Part II Policy Recommendations to Facilitate Water Marketing

- Part III Case Studies of Potential Water Transfers

- Part IV Concluding Reflections

- Appendix U.S. Department of the Interior's "Principles Governing Voluntary Water Transactions"

- Index