![]()

Part 1

The setting

![]()

1 The landscape of Japanese higher education

An introduction

Chris Carl Hale and Paul Wadden

Changing demographics, paradoxical realities

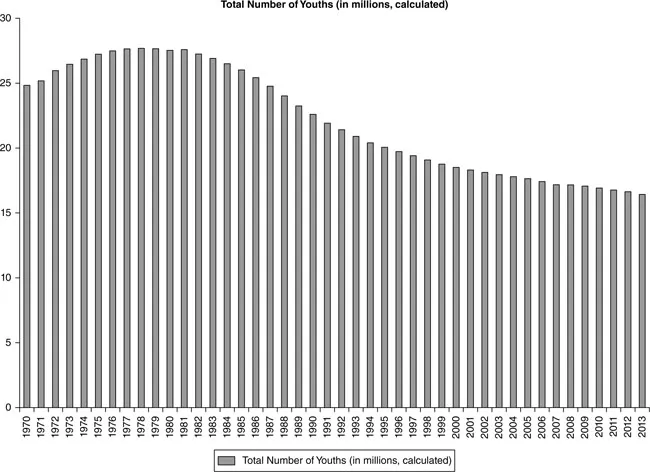

Over the last 25 years, since the original A Handbook for Teaching English at Japanese Colleges and Universities was published, there has been anxiety over Japan’s low birth rate, declining population, and dwindling number of college-age students. In such an environment, many readers of this new Handbook might wonder, “Why pursue a teaching career in Japan at all?” Looking at the trend line in Figure 1.1, one would certainly be forgiven, demographically, for climbing aboard the panic bandwagon.

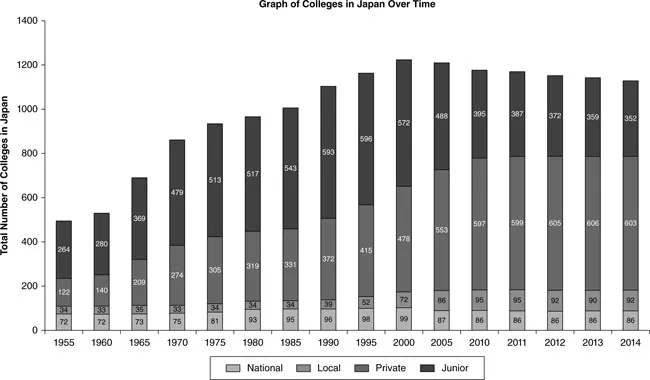

Since the early 1990s when the sharp decline of Japanese youth began, predictions of mass firings of faculty and mass shutterings of universities have abounded. Yet like many trends in Japan, there has been a paradoxical shift from what was expected to what has actually happened. According to MEXT, while the overall college-age population has significantly declined—from 2 million in 1990 to 1.2 million in 2017—the percentage of that population now attending college has sharply risen from 30% in 1990 to 50% today. And counter to widespread expectation (and even current belief), the overall number of four-year colleges and universities has steadily increased rather than decreased over this same period, as shown in Figure 1.2. This suggests there are more positions for foreign teachers at Japanese universities, and more diverse positions, than ever before.

In addition to the four-year colleges and universities shown in Figure 1.2, there are 352 two-year colleges in Japan; these junior colleges have, admittedly, seen a modest thinning out over the same period. Yet overall there are currently 1,133 institutions of higher learning in Japan, with an astonishing 274 more four-year colleges and universities than in 1993 when the original Handbook was published.

The contrasting shifts illustrated by these two figures suggest that Japanese higher education has skillfully surfed a demographic tidal wave—in part by enrolling more domestic students and in part (in a story untold by the chart) by attracting more international students, particularly from East Asia. As a result, Japanese college and university campuses are more diverse and dynamic than at any time in post-war history. Moreover, in order to attract international students, many universities are expanding their course offerings and even establishing full degree programs in English. As imperceptibly slow as it may appear to the long-time casual observer on the ground, the country is starting to re-envision itself as an educational hub for the region. At my university (Chris’s), for example, nearly 30% of the undergraduate students are non-Japanese, and foreign faculty—both language teachers and subject-specific professors—are being hired to teach them. In other words, despite popular belief and raw data suggesting an impending higher-ed apocalypse, the reality is that there has never been a better time to find work teaching English—and teaching in other academic fields in English—at Japanese colleges and universities.1

Perhaps what has changed in the past 25 years is that while the number of universities has risen, so too have the academic standards for their faculty. As will be evident in Chapters 2 and 3, which discuss in detail many aspects of university hiring and employment, the days of foreigners being offered full-time positions by showing up as native speakers with college degrees in hand have long since passed. And this is a good thing. In fact, the professional qualifications of the foreign professoriate in Japan are the best they have ever been.

Leaving generalizations at the door

A common refrain about higher education in Japan is that it isn’t very rigorous (some have even gone so far as to call it a “myth”).2 Among Japanese it is often said that universities are hard to get into (brutal entrance exams), but easy to get out of (a glide to graduation), which is generally the opposite of higher education systems in other developed countries. This generalization is bolstered by comparing the percentage of the population that enrolls in higher education of some kind (80% in Japan, compared with 69% in the U.K and only 52% in the U.S.) and university completion rates (72% in Japan, compared with 55% in the U.S. and only 44% in the U.K.). One interpretation of these OECD figures3 is that a lot more students in Japan attend a college or university of some kind, and they have a far easier time completing their study. In other words, the U.S. and the U.K. are more rigorous: fewer attempt to enter at all, and of those who do, fewer can “cut it” and graduate.

As we have spent a combined half-century working in Japanese universities, we can attest that there is some truth to this generalization. There are more than 1,100 colleges and universities, including junior colleges, and some are indeed less rigorous. If students can get to the first step at the bottom of the “escalator,” as another Japanese metaphor for college study depicts it, they can rise without much effort from freshman year to senior year and step off the top of the escalator with a diploma in hand. But we also both work at two universities that decidedly do not fit this characterization. Many of the authors of this volume can attest to schools that do not fit this stereotype either. Interestingly, one of the benefits of having more international students on Japanese campuses is that they are voting positively with their feet and expect quality teaching for their tuition payments. Thus, faculty are under pressure to “up their game” and abandon—or at least limit—old-fashioned pedagogies such as droning on in weekly lectures for an entire course with one multiple-choice exam at the end. New predominantly English-language universities are being founded, such as Akita International University and Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, as well as free-standing new colleges within traditional universities, such as Waseda University’s “School for International Liberal Studies” (SILS).4 Other trends putting positive pressure on courses and curricula are the Ministry of Education’s successful efforts to get universities to lengthen terms, regularize credit hours, and implement student evaluations, as well as the newfound emphasis companies are placing on continual and lifelong learning skills needed for success—for employees and employers—in the twenty-first century. A series of well-funded Ministry of Education initiatives to globalize Japanese higher education through massive multi-year grants—in particular, the Super Global University projects—has spurred innovative curricula at leading universities and raised the demand for qualified foreign teachers, scholars, and researchers.

One strategic generalization that we and other contributing authors have made in this book concerns the term “the Japanese university.” For us, this phrase functions in the same way that the term “species” does in biology: it names an overlying category of educational institutions within which there are many different types (subspecies such as “national,” “prefectural,” “private,” “elite,” “technology,” “liberal arts,” “foreign studies,” etc.) as well as significant differences in each individual institution as a phenotype. We urge you, the reader, to approach your particular school the way an anthropologist investigates a foreign culture: put aside your personal assumptions and cultural predilections and observe as clearly as possible the actual environment in which you work; it will be completely different from your university back home in Sydney, Liverpool, Hamilton, Dublin, Singapore, or San Francisco. It will also be significantly different from any previous school at which you worked in Sapporo, Osaka, Tokushima, or Fukuoka. Learn about its history (how and why it was founded), its faculties (which are largest and most influential), its organizational structure (and how power flows within it), and its student demographic. Observe without judgment the behavior of the faculty, students, and staff around you and try to discern the web of relationships and values in which they are embedded. Continually interview and casually question members of each group to better understand this unique island culture and ecosystem on which you have landed. Just as each community and each family is distinct, each university is one of a kind. The maps provided in the following pages won’t be the actual territory, but they may prevent you from getting disoriented in that territory as often, and when lost, may help you more quickly find your bearings.

Navigating this Handbook

This first section, Part 1, contains two important chapters dealing with how to get (and keep) both full-time and part-time university work in Japan. They describe positions, qualifications, hiring processes, typical responsibilities, and the general dos and don’ts of finding employment. For those seeking full-time positions, Chapter 2 identifies a fundamental yet common error of focusing one’s educational qualifications only on TESOL and applied linguistics, while Chapter 3 explores the potential to earn a decent living—and live a freer life—as a permanent part-timer. Chapter 4, “The chrysanthemum maze: understanding your colleagues in the Japanese university,” is essential reading for anyone trying to grasp the political, psychological, interpersonal, and administrative infrastructure of the Japanese university; it is a quasi-user’s guide for making sense of the functioning of your faculty and administration.

Part 2, “The courses,” begins with four chapters written by leading teacher–educators on principles and pedagogy to optimally teach the primary English skills courses—speaking, reading, writing, and listening—at Japanese universities. These are followed by chapters on the teaching of subject-specific courses (such as CLIL and EMI) and the art of presentation (both are expanding throughout college curricula), and by chapters on skills and pedagogy underlying nearly all university coursework—acquisition of vocabulary, use of technology, assignment of homework, and standards of evaluation.

Part 3, “The classroom,” focuses mainly on Japanese students. Who are they? What are their attitudes and expectations? Why are they often “silent”? What accounts for their interaction patterns? What is their educational experience to date? How can a teacher create engagement and heighten motivation? What particular dynamics exist between students and their “foreign teachers”? Why? How does national language policy from elementary school through university impact their language skills and learning styles? These topics—and many more besides—are explored in this section.

Part 4, “The workplace,” engages an even wider range of issues including those encountered by Japanese teachers of English, “non-native non-Japanese” teachers of English, and non-Japanese administrators. These chapters examine the challenges and contributions of non-native English teachers (belying the “native speaker fallacy” and the newly posited “native speaker learner fallacy”) and share the perspectives of two non-Japanese faculty who have served as senior administrators (a former university president and a current vice president for academic affairs). Other chapters appraise female–male dynamics in the university based upon a nation-wide survey (“‘He Said, She Said’: Female and Male Dynamics in Japanese Universities”) and the laws and labor conditions of the workplace, including possible recourse when conflict occurs (“Conflicts, Contracts, Rights, and Solidarity: The Japanese University Workplace from a Labor Perspective”). The final chapter, “Navigating the Chrysanthemum Maze: Off-hand Advice on How to Tiptoe through the Minefield of the Japanese University,” is a casual conversation between two contributing authors—and wizened language-teaching faculty—in which they ponder general rules of thumb for working in a university and elaborate on insights offered in this Handbook by recalling their own experiences.

Appendices are often regarded as superfluous, but we urge you to browse through the ones in this book. We include them because we wish someone else had compiled them previously so we could have used them. Appendix 1 features resources available to English teachers and foreign faculty, from professional associations to academic journals, and from useful websites to research groups (including some little-known but intriguing scholarly study groups). Appendix 2 offers a brief explanation of types of universities and how to find out more about them; some of this information is much more accessible these days as a complete list of Japanese universities is now available, by region, on Wikipedia, and many universities have their own English webpages. Appendix 3 presents (A) a hierarchical table of administrative offices at the typical university (it may need to be slightly reconfigured for your own...