- 268 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

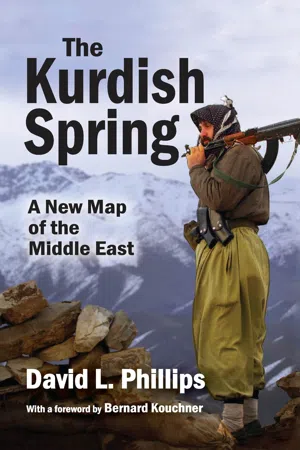

Kurds are the largest stateless people in the world. An estimated thirty-two million Kurds live in "Kurdistan," which includes parts of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran today's "hot spots" in the Middle East. The Kurdish Spring explores the subjugation of Kurds by Arab, Ottoman, and Persian powers for almost a century, and explains why Kurds are now evolving from a victimized people to a coherent political community.David L. Phillips describes Kurdish rebellions and arbitrary divisions in the last century, chronicling the nadir of Kurdish experience in the 1980s. He discusses draconian measures implemented by Iraq, including use of chemical weapons, Turkey's restrictions on political and cultural rights, denial of citizenship and punishment for expressing Kurdish identity in Syria, and repressive rule in Iran.Phillips forecasts the collapse and fragmentation of Iraq. He argues that US strategic and security interests are advanced through cooperation with Kurds, as a bulwark against ISIS and Islamic extremism. This work will encourage the public to look critically at the post-colonial period, recognizing the injustice and impracticality of states that were created by Great Powers, and offering a new perspective on sovereignty and statehood.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Kurdish Spring by David L. Phillips in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Middle Eastern History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

1

Betrayal

The twentieth century was a period of false promises, betrayal, and abuse for Kurds. The Kurds had national aspirations as the Ottoman Empire started to wane. They sought political support and protection from the Great Powers. Promises were made, but Kurds were ultimately abandoned. Hopes dashed, Kurds rebelled and were suppressed, their political rights and cultural identity brutally denied.

End of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire reached its zenith in 1453 with the conquest of Constantinople by Sultan Mehmed II. Its peak continued until the late sixteenth century under the sons of Suleiman Kanuni (“the Magnificent”).1 Yavuz Selim seized the Holy Cities in 1517, legitimizing the Ottoman Sultan as a caliph, a head of state. As the Ottoman Empire expanded, it created the millet system to manage relations with Christian and other minorities.2 “Millet” is derived from the Arabic word meaning “nation.” This system bestowed religious freedom on religious minorities as long as they swore fealty and paid taxes to Constantinople (“The Porte”). To manage its far-flung territories, the millet system allowed a degree of decentralization, feeding the empire’s coffers and ensuring stability. The millet system also allowed self-rule for ethnic minorities, who flourished under Ottoman rule. Many of the sultan’s viziers were ethnic Greeks, Arabs, or Persians.

The sultan was called “the shadow of God on earth.” He held absolute power.3 During the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, especially during the rule of Suleiman the Magnificent, the Ottoman Empire expanded and prospered. The Porte extended control from Southeast Europe into Central Asia and Mesopotamia. It ruled from the Caucasus on the North Black Sea coast to the Maghreb and the Horn of Africa. The string of conquests ended with defeat at the Battle of Vienna in 1683. The Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 ceded large swaths of territory in Central Europe. After centuries of successful expansion by the Ottoman Empire, a period of retrenchment and stagnation ensued.

Sultan Mahmud II, followed by his son Abdulmecid, tried to stem the Ottoman Empire’s decline, initiating Tanzimat reforms through the Imperial Decree of Gulhane in 1839.4 “Tanzimat” means reorganization. Tanzimat reforms were a response to nationalist movements, including demands of the Kurds. The 1856 Reform Decree was intended to provide modern citizenship rights. It sought to enhance Ottomanism by requiring submission to a single code of laws—in effect centralizing power. The Porte thought that Tanzimat would restore the loyalties of Greeks, Armenians, and Kurds. It also believed that modernization would deter European powers from trying to interfere in the Ottoman Empire’s internal affairs. However, Tanzimat did not deter Europe’s meddling or enhance the loyalty of groups under the millet system, which included the Kurds. Instead of fostering loyalty and coherence, it fueled dissent. Kurds, Greeks, Serbs, and Russian-backed Armenians rebelled.5

During the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–29, the fourth of seven wars between the Ottoman and Russian empires, the Kurds initially acted as a bulwark against Russian expansionism. Bedr Khan Beg, a Kurdish tribal leader and emir from Djazireh, was a powerful hereditary feudal chieftain of the Bokhti tribe. Since the fourteenth century, his clan enjoyed uninterrupted rule of Cizre-Botan, a wealthy and prosperous emirate. He was given the title of “Pasha,” in recognition of his contributions to the empire and his help fighting Armenians. 6 But Bedr Khan rebelled against the Porte, demanding an independent Kurdistan in 1834. He organized Kurdish tribes into a disciplined army and struck an alliance with the chieftains of Kars in North Kurdistan and with Emir Ardelan in Eastern Kurdistan. Bedr Khan established control over a large part of Ottoman Kurdistan by 1840.

The Ottoman army launched a counterattack. English and American missionaries turned the Christian tribes against Bedr Khan. In 1847, Osman Pasha persuaded Yezdan Sher, Bedr Khan’s nephew, to join the Ottoman side. With the eastern flank exposed, Bedr Khan fled Djazireh for the more easily defensible fortress of Eruh. He was finally defeated, exiled to Crete in 1850, and died in Damascus in 1868.7

The Ottoman Empire was challenged again during the Russo-Turkish War of 1877–78. The Porte faced a growing insurrection by Armenians. Sheik Ubeydullah, a member of the powerful Kurdish Semdinan clan, took advantage of the empire’s diverted attention. He declared an independent Kurdish principality and demand recognition by both the Porte and Persia’s Qajar dynasty.8 Initially, the Ottomans supported Sheik Ubeydullah, who stood against Armenian separatists fighting for independence. But the Porte reversed its stance in 1880, violently suppressing Sheik Ubeydullah’s bid for self-rule.9 In response to the rise of Armenian Committees, it recruited irregular Kurdish militias to fight Armenian pro-independence groups beginning in 1891. The Kurdish cavalry was called “Hamidieh,” after Sultan Abd-ul-Hamid II. Under instructions from the Porte, the Hamidieh took an active part in the massacre of Armenians at Sasun and other Armenian-populated villayets between 1894 and 1896. Kurds sought regional autonomy in exchange for their service, demanding the appointment of Kurdish-speaking officials and the use of the Kurdish language in local government and education systems. They also sought the right to practice Shari’a and customary law.

Russia played a double game. It supported both Armenian and Kurdish nationalism, as part of its strategy to diminish the Ottoman Empire. In fact, Moscow did not want either an independent Armenia or Kurdistan. It had its own expansionist designs on Eastern Anatolia. The young Turks who seized power in 1908, targeted populations they thought were sympathetic with Russia. Armenians and other Christian communities were suspected of treason or espionage and deported. Kurds were allowed to take over Armenian properties. Enver, Cemal, and Talat Pasha—the so-called “three pashas” who led the Committee of Union and Progress (CUP)—issued orders in support of the Armenian Genocide.10

Empire’s End

World War I marked the end of the Austria-Hungarian and the Ottoman Empires. The Russian Empire also collapsed through pressure from Bolsheviks, which led to the abdication of Czar Nicholas II. During the early twentieth century, ethno-nationalism replaced allegiance to distant monarchs. “Kurdish nationalism was the illegitimate child of Turkish nationalism.”11

Istanbul entered into a secret alliance with Germany in August of 1914. It joined the Central Powers, Germany and the Austria-Hungarian Empire, against the Allies—France, Britain, and Russia, who were joined by Japan and the United States.12 Washington entered the war in April 1917, after the German practice of unrestricted submarine warfare sunk merchant ships with Americans on board. Turkish forces engaged on multiple fronts. They fought Greeks, Assyrians, and Armenians in Asia Minor. Turkish forces engaged the Russian Army in the Caucasus. Turkish forces were also in the East. They launched a Sinai offensive, challenging Britain’s control of the Suez Canal and its holdings in South Asia.

The tide turned against the Turkish army after initial victories. Russia fought fiercely, despite the gathering storm of its civil war. In June 1916, Britain instigated Arab tribes to revolt. British forces conquered Damascus, Mecca, and Medina after a two-year siege. They captured Palestine in January 1917, Baghdad and Mesopotamia in March 1918. Finally, the Kirkuk garrison surrendered in May 1918. All Arab-populated regions of the Ottoman Empire, including Mosul, had succumbed to British or French forces.

Final defeat of the Ottoman Empire was enshrined with the Mundros Armistice of October 30, 1918. The CUP cabinet resigned; Enver, Cemal, and Talat Pasha fled the country on November 7. Mundros marked the Ottoman Empire’s humiliating and unconditional surrender. The Allies established the right to occupy any area of the empire. The Straits, the Dardanelles, and the Bosphorus were opened to Allied warships, allowing control over transportation and maritime activity. Except for the gendarmerie, all Ottoman forces were demobilized. Food, coal, and other materials were relinquished to the Allies. Ottoman finances were subject to regulation by an Allied commission, with a portion of revenues dedicated for reparations.13 Mundros made allowances for Armenians, Georgians, and Azerbaijanis.14 Ottoman security forces, including the gendarmerie, were removed from the six Armenian-populated eastern provinces. All detained Armenians were immediately released.15

Britain developed a plan for administering the Kurdistan region. British officers with extensive experience in Kurdish affairs, E. B. Sloane and E.W.C. Noel, initiated talks with local Kurdish leaders. They recommended the establishment of a British-sponsored Kurdish tribal council to Britain’s High Commissioner in Baghdad, Sir Percy Cox. He endorsed the proposal to Britain’s Foreign Office on October 30, 1918. Cox went even further, proposing the establishment of a Kurdish state in South and West Kurdistan. Kurds were unified, for the moment, motivated by fear of punishment for crimes they committed against Armenians and Assyrians. However, divisions between Kurdish leaders soon surfaced. Throughout late 1919 and most of the following year, British troops were engaged on the Northern frontiers of Mesopotamia. Revolts flared up everywhere. Some were inspired by the Turks in an attempt to drive British troops out of the Mosul area. Some were simply a reaction by Kurds to the imposition of yet another outside authority.16

Cox’s recommendation was entirely consistent with Britain’s practice of arbitrary decisions impacting peoples in the region. With the war still underway, Sir Mark Sykes of Britain and George Picot of France started secret negotiations in November 1915. The Sykes-Picot Agreement, officially called the Asia Minor Agreement, was finalized on May 16, 1916. The accord divided Ottoman Asia into British and French zones of influence. The Baghdad and Basra villayets were assigned to Britain. Sykes-Picot assigned the Mosul villayet to France.17 Kurds received no favor. Britain and France viewed them as peoples subject to exploi...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Author’s Note

- Introduction

- Part One

- Part Two: Abuse

- Part Three: Progress

- Part Four: Peril and Opportunity

- List of Abbreviations

- Index