![]()

1

Model Programs and Service Delivery Approaches in Early Childhood Education

Joan L. Ershler

University of Wisconsin-Madison

History and Rationale for Early Childhood Education

Discussions about the value of early education and how best to provide early education services have had a recurring presence in the literature. For over 2,000 years, issues related to the “why” and “how” of teaching preschool-aged children have engaged philosophers, psychologists, educators, and parents (Borstellman, 1983). Contemporary early educators attempt to grapple with issues similar to those that have occupied their predecessors. Because there are valuable insights to be gained by understanding “our professional ancestors,” it is important to make note of some of the sources of the ideas and questions still being addressed in early childhood programs (Hooper, 1987).

One way to conceptualize the rationale for providing early education services is to contrast two historical schools of thought whose legacy is expressed in current service delivery approaches in early childhood education (Carter, 1987). Plato expressed the first of these perspectives, emphasizing the “equalizing” nature of public education (Plato. 1945). Advocating placing children early in life in state-run schools, he believed that educating children uniformly would promote the egalitarian growth of abilities and would diminish the influence of less than desirable home environments. In contrast, in the 17th century Comenius proposed that mothers were the best educators of their young children (Sadler, 1969). Comenius’ belief in the educational benefits that mothers’ emotional, energy, and time commitments provided to their children led him to formulate guidelines for educating young children in their homes.

Plato’s and Comenius’ views may be conceptualized as two poles on the continuum of school-based versus home-based approaches in early education. Current issues related to the school-home relationships in the education of young children reflect this continuum. Thus, some early educators express their concern with ways to involve parents in school programs to enhance their children’s learning (e.g., Grotberg, 1972). Others are interested in developing programs that support or complement the training that families already provide (e.g., Shearer & Shearer, 1976). In either case, the nature of parental involvement in early education programs, an issue that is derived from varying perspectives along the Platonic-Comenian continuum, is still being discussed (see Meisels & Shonkoff, 1990, and Paget, Chapter 3, this volume).

Historical discussions addressing the issue of “how” to educate young children may also be found. In the 1700s, Jean Jacques Rousseau’s belief in the innate goodness of children led him to propose early schooling that enabled children to direct their own activities, free from the constraints imposed by “society” (Rousseau, 1961). Such child-centered education, emphasizing activity and the use of the senses, was thought to foster the development of each child’s moral and intellectual potential.

Rousseau’s idealism was embraced yet modified by Friedrich Froebel, who has been credited with establishing the kindergarten movement in early 19th-century Germany (Deasey, 1978). His advocacy of early education in the Rousseau tradition was carried to the United States by Elizabeth Peabody, who established the first Froebelian kindergarten in Boston in 1860. Many aspects of the Froebelian kindergartens are present today in preschool programs.

Following Rousseau’s philosophy, Froebel advocated respect for young children’s needs and the importance of sensory training. He specifically promoted the importance of play as the educational “medium” through which children could reach their intellectual and emotional potentials. Perhaps Froebel’s major contribution to early education as a separate field of study and practice was his articulation of a theory of child development and a related theory of early childhood education. Suggesting that children progress through different age-related “phases,” he proposed that certain materials, or “gifts,” be incorporated into the kindergarten curriculum to correspond with these phases, hence enhancing development. This notion of appropriate “match” (Hunt, 1961) has been the cornerstone of many contemporary early education programs.

The final historical figure in this brief overview is Maria Montessori, who in the early part of this century continued the Froebelian tradition within a different context (Montessori, 1964). Concerned with the welfare of young, poor urban children in Italy, she established her “children’s houses.” Thus, reiteration of the Platonic notion of compensatory early education may be seen in Montessori’s work. Like Froebel, Montessori implemented an early education curriculum that was founded on a developmental theory, employed play as the instructional method, and sequentially introduced developmentally appropriate materials designed to facilitate sensory and cognitive skills.

Although the historical overview presented is certainly not complete, it does represent much of the thinking that has shaped the field of early education. This thinking may be summarized as follows:

1. Early education at the very least may serve to complement what children learn in their homes. At the most, it may facilitate learning that has not yet occurred.

2. A useful approach for planning a curriculum for young children is to employ a theory of development or learning.

3. An important component of early education programs is active learning, or learning through play.

Each of the approaches described in this chapter has addressed these three points. In the first part of this chapter, the characteristics of these “models,” or conceptual frameworks, are described, along with exemplary programs. As becomes evident, the application of these points differs among programs adhering to each conceptual model. Following a discussion of the model approach, issues related to the evaluation of model programs and representative research are presented. Finally, the third part of this chapter is devoted to issues related to the school psychologist’s growing involvement in the field of early childhood education. This description is limited to service delivery for 3- to 5-year-old children who may be at risk because of economic hardship and/or family stress (see Telzrow, Chapter 2, this volume, concerning children with special education needs for a description of special services).

Theoretical Perspectives in Program Development

Overview: The Model Approach

Although a steady stream of discussion about early education has been evident historically, there appears to have been a burst of energy in the area beginning in the 1960s that continues to this day (Johnson, 1988). This has been reflected in the number of publications devoted to various aspects of early childhood education. To a great extent, the onset of this period of growth was due to a societal commitment to improving the lives of economically disadvantaged children, articulated by President Johnson’s War on Poverty. Concomitantly, the emergence of Piagetian theory in the fields of psychology and education fueled more discussions about the practical implications of various theoretical approaches. The increase in the demand for compensatory early education programs, as well as the re-introduction of cognitive-developmental theory as an alternative to psychodynamic and behavioral approaches, contributed to the increase in program research and development during the 1960s.

One outcome of the increase in activity in the 1960s was the articulation of the model approach in early education. Discussion centered in general around how best to translate psychological theory into educational practice, and specifically how best to derive early education principles from developmental and learning theories (e.g., Bloom, 1964; Day & Parker, 1977; Hunt, 1964; Kohlberg, 1968; Murray, 1979; Ripple & Rockcastle, 1964; Shapiro & Biber, 1972). Prescriptions for programs (i.e., how to teach and what to teach) were often defined by beliefs about the ways young children develop and learn. These beliefs were, in turn, derived from theory and supporting research.

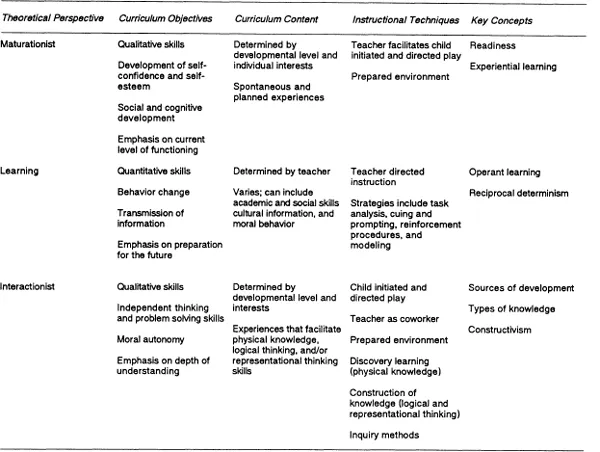

An overarching assumption of the model approach is that a specific theory and the empirical work it generates may lend themselves to practical application. Obviously there is no single theory concerning how children develop and learn and, consequently, how they should best be taught. However, there are clusters of approaches that share assumptions about the nature of young children’s development that have given rise to programs that are theoretically compatible. These clusters or theoretical frameworks may be categorized as maturationist, learning, and interactionist (Evans, 1975; Kohlberg, 1968). A summary of the characteristics of these models is presented in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1

An Overview of the Model Approach in Early Childhood Education

Maturationist View

Assumptions and Goals. The maturationist perspective is based on the belief that children’s development is governed by a biologically based schedule. That is, children’s abilities and the general timing of their appearance are essentially predetermined (cf. Nagel, 1957). Although maturational unfolding typically has been discussed in the context of gross and fine motor development (e.g., Shirley, 1931–1933), its principles may also be applied to understanding other developmental domains, such as social and emotional growth (e.g., Erikson, 1950, 1980; Isaacs, 1933) and cognition (Isaacs, 1930). Maturationists do not deny the importance of factors other than biological pre-programming in facilitating development, such as environmental stimulation or experience; they simply consider this pre-programming to be the most important factor in explaining development.

Programs derived from a maturationist perspective often place heavy emphasis on certain tenets of psychodynamic theories of development and progressive educational philosophy (Zimiles, 1987). The importance of early experience for subsequent emotional, social, and cognitive development is a core belief, reflecting the writing, for example, of Freud and Erikson. The influence of the psycho-dynamic tradition may also be seen in the frequently articulated relationship between emotional well-being and rationality, as if stable affect “fuels” intellectual thought (cf. Piaget, 1981). Finally, early education programs within this perspective advocate the pedagogically compatible notion of the importance of individual exploration as a means of tying direct experience with learning. These ideas are founded in the progressive educational philosophy exemplified by the writings of John Dewey (e.g., 1944).

The goal of the maturationist-inspired early education program, then, is to provide a nurturing and supportive environment, one in which the child’s innate strengths (e.g., curiosity, desire for competency) will be allowed to blossom, while less desirable characteristics (e.g., lack of cooperation) will be brought under control (Kohlberg & Mayer, 1972). Thus, educational objectives are stated in global, qualitative terms, often related to the development of competency and self-esteem, which are considered necessary for cognitive and social development. The manner in which each child makes use of the available experiences to accomplish these objectives depends on his or her unique timetable of naturally unfolding developmental processes.

Curriculum, Teacher Role, and Instructional Methods. The curriculum within the maturationist approach can best be described as child centered. That is, curriculum content is determined by both children’s developmental levels and their interests. In terms of providing developmentally appropriate activities, this means that it is assumed that children cannot (indeed, should not) be “pushed” to learn or perform beyond their current abilities. There is an emphasis on “readiness,” about which children are considered to be the best judges. Children are therefore expected to direct their own activities based on their interests. As much as possible, children’s experiences are incorporated into the activities, which are supplemented with planned, shared experiences (e.g., field trips), providing a broader experiential base. In all, the curriculum is designed to facilitate each child’s competency at his or her current level of functioning rather than offering specific skill training for the future, because a solid foundation is considered the best preparation.

Teachers working within the maturationist perspective are likely to possess a solid understanding of child development, enabling them to make appropriate choices when planning activities and providing materials. Although some of the experiences teachers present are those many preschool-aged children find interesting, others may be unique and reflect a particular child’s interest or experience. Typically, activities are organized into interest centers, with related activities (e.g., animal care, large motor, art, small manipulative) located within these areas, and children are free to initiate and direct their own activities throughout the day.

Teaching techniques facilitate both individual expression and social development. Following the children’s lead, teachers comment on their activities, similar to the behavioral strategy of attending (Forehand & McMahon, 1981). When new materials or activities are introduced, they are presented as options, ones in which the children have a choice to participate. Cooperation and getting along with others are facilitated through guided reasoning and modeling. Generally, teachers fulfill a supportive, nurturing role, providing an emotionally safe environment, one in which children feel secure and competent enough to explore and learn through playing (cf. Ainsworth, 1967).

Exemplary Programs. Those familiar with early childhood classrooms are likely to see elements of the maturationist approach in many programs not explicitly driven by this perspective. The themes of supporting feelings of individual competence, social development, and tying experience to learning are familiar ones in early education. However, as “common sense” as these principles may seem, in programs explicitly derived from the maturation perspective, the rationale for these principles stems from a strongly articulated theory, and their expression is well-thought through and carefully implemented. Two such programs are The Children’s Center, administered through Syracuse University, and the Bank Street Approach, administered through the Bank Street College of Education.

The Children’s Center, originally established to help economically disadvantaged children in the 1960s (Caldwell et al., 1968), became the school-based arm of a larger intervention project, the Family Development Research Program (FDRP; Honig & Lally, 1982; Lally & Honig, 1977). The primary objectives of the FDRP were to: (a) provide parenting instruction and support to low-income parents with limited formal education, and (b) promote the development of emotionally healthy and competent young children. This was accomplished through both a home-based and a school-based approach.

The home-based component of the FDRP was implemented by trained para-professionals (Child Development Trainers) who fulfilled the roles of teacher, friend, and advocate for the participating families. Mothers, rather than their children, were the focus of this component, with the Child Development Trainers providing a myriad of support services, ranging from helping to gain access to community services to modeling appropriate interactions with children.

In contrast to the home-based program, The Children’s Center was designed to facilitate children’s development, adhering closely to an Eriksonian model. That is, objectives of the program emphasized age-appropriate psychosocial goals, such as developing trust and autonomy (Honig, 1987). These were considered crucial for the development of a positive self-concept and feeling of competence, personality characteristics...