eBook - ePub

The North American Trajectory

Cultural, Economic, and Political Ties among the United States, Canada and Mexico

- 198 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The North American Trajectory

Cultural, Economic, and Political Ties among the United States, Canada and Mexico

About this book

North America is steering a new course, with the United States, Canada, and Mexico moving toward continental economic, integration. This book examines basic value changes that are' transforming economic, social, and political life in these three countries, demonstrating that they are gradually adopting an increasingly compatible cultural perspective. A narrow nationalism, dominant since the 19th century, has slowly been giving way to a more cosmopolitan sense of identity. As old economic boundaries become outmoded, a North American perspective makes greater sense. To what extent, then, do the three North American publics - I each with its own heterogeneities and tensions - share a common culture? That question can only be answered if we have some yardstick by which to measure their cultural similarity. These societies are far from identical. But data from the 1990- 1991 World Values survey, drawn from 43 societies around the world, show that on crucial topics, the core values of the American public are significantly closer to those of the Canadians and (to a somewhat lesser extent) to those of the Mexicans, than they are to those of most other peoples in the world. Furthermore, time series evidence indicates that the values of the three North American publics have been converging. This book draws on a unique body of directly comparable cross-national and cross-temporal survey evidence to show that what Americans, Canadians, and Mexicans want out of life is changing in analogous ways. These changes, coupled with sociostructural transformations, are reshaping peoples' feelings about national identity, about trusting each other, and about the balance between economic and non-economic goals. North American economic integration is being reinforced by the gradual emergence of increasingly similar cultural values.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The North American Trajectory by Neil Nevitte in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & International Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in North America

INTRODUCTION

North America is steering a new course. Since the mid-1980s, the United States, Canada, and Mexico have been moving toward continental economic integration, culminating in the establishment of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1994. This book focuses on how changes in basic values among the publics of the United States, Canada, and Mexico are transforming economic, social, and political life, giving these countries an increasingly compatible cultural perspective. In the long run, these changes have important implications for economic and political cooperation between these countries.

North American integration has been highly controversial, with orga-nized labor in the United States opposing it for fear that it would bring a massive loss of American jobs to Mexico (the "giant sucking sound" that H. Ross Perot said we would all hear). Conversely, some observers in Mexico have blamed NAFTA for the financial crisis linked with the 1994 devaluation of the peso. In Canada, NAFTA was evoked as an argument by both sides in the 1995 referendum on Quebec separatism: Opponents of secession argued that an independent Quebec would risk losing the advantages of free access to North American markets, while independence advocates took it for granted that they need not worry about the economic consequences of secession because Quebec is already part of an economic entity much larger than Canada. In the United States, perceptions of cultural differences and economic competition, in a time of high immigration flows and high unemployment rates, have given impetus to proposed curbs on immigration.

Nevertheless, our evidence indicates that the long-term trend in all three countries is toward an increasingly global perspective. A narrow nationalism that had been dominant since the nineteenth century is gradually giving way to a more cosmopolitan sense of identity. A North American perspective makes sense because it is increasingly clear that the old economic boundaries are becoming outmoded.

In 1989, the United States and Canada, which already exchanged more trade than any other two countries in the world, ratified a comprehensive bilateral trade agreement. Almost immediately afterward, U.S. and Mexican officials began discussing a similar agreement, and by 1994 the three countries had established the North American Free Trade Agreement. Some see NAFTA as an initial step toward an even more ambitious project, a free-trading community that will encompass two continents stretching from Alaska to Cape Horn. But even if that vision is not realized, the North American trading bloc with its 360 million people and a combined annual production of $6 trillion constitutes the world's largest international economic power, its closest rival being the European Union with an internal market of 346 million people and $5 trillion in annual output.

For the United States, Canada, and Mexico, the move toward conti-nental free trade represents a policy shift, one that raises a variety of fundamental, theoretical, and practical questions: Why are the three countries pursuing continental economic integration? What explains the timing of the policy shift? And can these three countries work together effectively?

The economic case for free trade is a powerful one. Some see NAFTA as a strategic response to the new realities of globalization and most particularly the economic face of globalization—the emergence of new trading blocs (Dominguez 1992; Ostry 1992). Today, the North American economies face a dynamic, prosperous, and expanding European Union, which is merging the economics of its member states into a single market. Having absorbed Greece, Spain, and Portugal in the 1980s and East Germany in 1990, the European Union admitted Sweden, Austria, and Finland to membership in the early 1990s, to constitute a fifteen-nation economic and political alliance. Czechoslovakia, Poland, Hungary, and Turkey are seeking admission. North Americans also confront the challenge of competing with the dynamic East Asian economies led by Japan, China, South Korea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

From a continental perspective, NAFTA can also be seen as the logical extension of evolving patterns of closer commercial cooperation, the origins of which can be traced to the 1950s and 1960s (Smith 1988). And from the standpoint of neoclassical economics, the drive toward continental free trade is perfectly logical. The push to expand access to larger markets is a widely recognized means of stimulating economic growth: it is the strategy of choice for countries aiming to maximize returns from the economies of scale, for lowering costs, for increasing competitiveness, and for exploiting comparative advantages most efficiently. From this viewpoint the puzzling question is not Why are the United States, Canada, and Mexico pursuing free trade now? but Why didn't they do so decades ago? Much of the answer lies in psychological and cultural barriers.

Economic interests unquestionably are vital to the dynamics of integration. But economists were among the first to recognize that economic perspectives alone could not provide a complete or convincing account of why countries move toward economic integration. Economic explanations fall short not just because of the sizable gap between economic theory and behavior (Johnson 1965; Milner and Yoffie 1989) but also because they fail to take into account the crucial role that noneconomic factors play in the dynamics of economic interdependence (Cohen 1990). Investigators attempting to provide a more comprehensive account of integration have consequently focused on two questions: Which noneconomic factors are crucial? And precisely how do these noneconomic factors contribute to the process of integration?

In the 1960s and 1970s, theorists working from a variety of perspec-tives argued that no account of integration would be complete without considering the role of political factors. Functionalists, neofunctionalists, communications theorists, and revisionists made considerable progress toward bringing politics back in, although no consensus emerged about the relative importance of leadership, trade, levels of institutional coordination, or styles of decision-making (Etzioni 1965; Haas 1971; Nye 1968; Puchala 1971; Lindberg and Scheingold 1970). Since the late 1970s, realists, institutionalists, and others have further expanded those political perspectives by bringing the state back in. Those efforts draw attention to important strategic concerns, to the role that interest groups play, to the connection between state and societal factors, and to the interdependence of domestic and international decision-making (Milner 1988; Cohen 1990; Gourevitch 1986; Nye 1988; Putnam 1988).

This book builds on both classic and recent contributions to our un-derstanding of the politics of integration but it takes these perspectives in a different direction. We argue that no explanation of North American economic integration is complete without considering the role that values play in the process of integration. More particularly, our focus is on the values of mass publics, and our goal is to move mass values from a marginal position to the center of analysis. We argue that mass values have shaped the politics of continental integration in significant ways and, further, that value change among the American, Canadian, and Mexican publics helps to explain why political leaders pursued NAFTA when they did. The book draws on a unique body of directly comparable cross-national and cross-time evidence to show that what Americans,Canadians, and Mexicans want out of life is changing and that these changes, coupled with sociostructural transformations, are reshaping people's feelings about national identity, about trust, and about the balance between economic and noneconomic goals.

Values play a central role in the classic literature on integration, with a variety of theorists arguing that values are crucial because they help shape the dynamics of integration in significant ways (Deutsch et al. 1957; Haas 1958). Those theoretical perspectives provide a useful starting point for, as we will see, the North American evidence indicates that there is a good deal of empirical support for these original speculations. Contemporary perspectives on integration, particularly those examining how international and domestic factors interact to determine the outcomes of such trade policies as NAFTA, have drawn attention once again to the significance of public values for another set of reasons: they bring into focus their political significance (Krasner 1978; Katzenstein 1978). A particularly forceful explanation of why publics and their values count in the politics of integration is provided by Putnam, who suggests that the politics of international negotiations can be understood as a two-level game (1988:434). He argues:

At the national level, domestic groups pursue their interests by pressuring governments to adopt favorable politics, and politicians seek power by constructing coalitions among these groups. At the international level, national governments seek to maximize their own ability to satisfy domestic pressures, while minimizing the adverse consequences of foreign developments. Neither of the two games can be ignored by central decision-makers, so long as their countries remain interdependent yet sovereign (p. 436).

The values of mass publics matter for two reasons: First, those nego-tiating trade agreements like NAFTA do not have independent policy preferences (ibid.). Second, for such agreements to be politically acceptable, they must satisfy not only the other parties at the negotiating table but also the relevant domestic constituencies they represent. They must satisfy them because these domestic constituencies can support or block ratification of these agreements. The mechanisms for ratification, Putnam points out (pp. 436-40), can be either formal or informal and in each case they also depend upon the institutional rules of the game and opportunities. Those who count as the relevant domestic constituencies also differ, depending upon a variety of factors such as how open or closed the given governing regimes are.

Classic analysis of international relations has tended to downplay the role of public opinion. But during the 1990s, it became increasingly clear that the beliefs and values of mass publics are coming to play a crucialrole. For example, the fact that the Danish public blocked ratification of the Maastricht treaty in 1992 had a massive impact on efforts to move toward a common European currency, and on the political integration of the European Union more generally. In the Danish case, the tool for ratifying public support for Maastricht was a national referendum and the political significance of public opinion was clear and direct. The Danish public rejected the Maastricht proposals, which would have propelled Denmark toward greater integration with its European partners; in doing so, they threw the entire European Union into a crisis that was only partly resolved when the Danish public later approved a revised version of the referendum in 1993. In the United States, public preferences are given voice by the constitutional provision requiring that treaties be ratified by a two-thirds majority in the Senate. There is no equivalent constitutional requirement in Canada, but Canadian-U.S. relations are so highly charged that the Canadian government felt compelled to go to the people by calling a federal election in 1988 on the issue of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement. The Canadian public then ratified the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement by returning the government to office. In Mexico, with a less open regime, the opportunities for ratification by the public were far more constrained and the size of the relevant public more limited. But even there, considerations of credibility and face-saving played a role.

In the United States, on the other hand, a dramatic increase in public awareness and involvement took place as NAFTA moved toward ratification by Congress in 1993. Until the final week, it was uncertain whether NAFTA would be accepted by the U.S. Senate, and President Clinton was able to swing sufficient votes for passage only by massive concessions to key constituencies. Because a vote against the trade agreement was considered politically safe, a majority of those who were elected by narrow majorities voted against NAFTA in the Senate. Most economists in the United States agreed that NAFTA was likely to have a favorable overall impact on the U.S. economy. But its narrow last-minute victory demonstrated that political considerations play a crucial role in global economics.

Bringing Values Back In

The idea that values matter to integration is not new, though recent work in political economy sometimes loses sight of it. The political ac-counts of integration that emerged in the 1960s and 1970s all recognize that values play a role and that value compatibility between political units is conducive to integration. Some observers emphasize the importance of elite values. Schmitter, for example, argues that "the more complementary elites come to acquire similar expectations and attitudes toward the integrative process, the easier it will be to form transnational associations and to accept regional identities" (1971:253). Others, like Jacob, include entire communities: "For integration to occur among two or more existing communities," he argues, "requires that values shared with each become shared with each other" (1964:210). But the most comprehensive account of the role that values play in the integration process springs from a still earlier body of work.

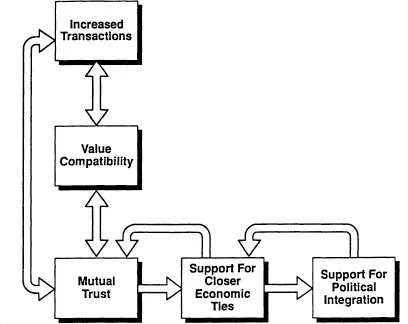

More than forty years ago, a group of scholars concerned with the prospects of securing peace and prosperity in West Europe joined forces to explore a common question: how to achieve greater cross-national integration through strategic institution-building. From these efforts, and drawing on comparative historical evidence drawn mainly from European case studies, Deutsch and colleagues (1952, 1957, 1963) developed a social learning perspective linking cross-national transactions to economic and political integration. Deutsch argued that high levels of transactions between peoples (the movement of peoples, cross-border commerce, and communication flows) encourage greater similarities in main values. Similarities in main values interact and are conducive to greater mutual trust between different peoples. Higher levels of trust, in turn, encourage greater cooperation and economic integration. And economic integration, Deutsch concludes, is conducive to greater political integration. The essential chain of reasoning linking these elements is summarized in Figure 1.1. Deutsch's historically informed account of how values shape the process of integration is a plausible one and, indeed, the essential elements of that perspective remain influential; they are reflected in subsequent versions of integration theory (Lindberg and Scheingold 1970; Nye 1976; Diebold 1988). Moreover, some of the basic elements of this perspective have been tested in a number of settings and the weight of the accumulated evidence appears to work in ways that are consistent with that formulation.

In the North American context, for example, the signing of the Canada-U.S. Free Trade Agreement indicates a mutual commitment to greater economic integration between the two countries. Deutsch's perspective implies that the signing of that agreement should have been preceded by changes in cross-border transactions. It was. The volume of Canada- U.S. two-way border crossings (the movement of people) rose from seventy-two million visits in 1980 to ninety-four million visits in 1989 (Statistics Canada 1991). Commercial and financial transactions also increased sharply over the period leading up to the agreement (Schott and Smith 1988).

For Deutsch, the importance of the high frequency of cross-border transactions is that these exchanges are conducive to mutual responsiveness and trust (Deutsch et al. 1957). With increasing rates of trade, diplomatic exchanges, tourist flows, and other types of interaction, the expectation is that different nationalities will find each other increasingly predictable and hence trustworthy; it is a learning process in which positive reinforcement leads to positive expectations and behavior. This emphasis on the importance of mutual trust is also a central theme in the political culture literature. The idea that interpersonal trust plays an important role in both economic and political cooperation has been confirmed by a large body of research (Wylie 1957; Banfield 1958; Almond and Verba 1963; Pruitt 1965; Easton 1966; Hart 1973; Luhmann 1979; Hill 1981; Miyake 1982; Abramson 1983; Inglehart 1990).

Figure 1 Values and the dynamics of integration

Empirical research about trust between different nationalities is rela-tively scarce, but the available evidence indicates that trust between different nationalities is a relatively stable attribute (Deutsch et al. 1957; Merritt and Puchala 1968; Nincic and Russett 1979; Inglehart 1991). The trustworthiness of thirteen nationalities was rated by nine West European publics in 1976 and then again in 1986. The rankings were virtually identical over the ten-year period, with a modest tendency for all nationalities to become more trusted. Trust ratings are highest between pairs of nationalities who share a common language group and, as Deutsch would expect, between those who have democratic political institutions. Moreover, the more prosperous nationalities tend to be the most highly trusted. Each of these factors turn out to be significant at the .0001 level and together they explain 72 percent of the variance in crossnational trust (Inglehart 1991). The experience of being on the same or opposite sides in World War II left an enduring imprint on the orientations of European publics; for example, in the 1950s the French and German publics distrusted each other deeply (Merritt and Puchala 1968). But the experience of working together within a successful set of European institutions seems to have had a gradual but ultimately significant impact. By 1980, the French regarded the West Germans as their closest ally and the nationality they trusted most (Inglehart 1991).

Both Deutsch's theory and the lessons from the European Union experience lead one to expect that the rate of interactions generated by NAFTA would have a similar effect between the three North American countries. Feelings of trust or distrust are central because they encourage or present serious obstacles to integration. To what extent, then, do the North American publics trust each other? As Figure 1.2 shows, there are significant asymmetries. The American public feels a great deal of trust for ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 Cultural, Economic, and Political Change in North America

- 2 Changing Patterns of World Trade and Changing North American Linkages

- 3 Compatibility and Change in the Basic Values of North American Peoples

- 4 Declining Deference to Authority and Rising Citizen Activism

- 5 In Search of a New Balance between State and Economy, Individual and Society

- 6 Political Integration in North America?

- 7 Conclusion

- References

- Index