![]()

1

Tropical rain forests and deforestation

Tropical rain forests thrive in the warm, wet environments of the humid tropics. The superb conditions for plant growth there allow a profusion of forests with a great diversity in species composition, but at the same time give rise to poor soils that make it difficult for farmers to capitalize on them. Farming can easily become unsustainable if practised too intensively on low quality deforested land. The great contribution that tropical rain forests make to the world’s biological diversity is not just in their huge species content but in the variety of different types of tropical rain forest. The next section looks at each of the main types of rain forest in turn, and is followed by a review of the distribution of forests in the humid tropics. We lack estimates of the global and national areas of tropical rain forest and are forced instead to list areas of ‘tropical moist forest’ – the collective term for all closed forest in the humid tropics, including both tropical rain forest and the tropical moist deciduous forest found in seasonal areas. Crucial to the debate about tropical deforestation is the rate at which it occurs, but since estimates are influenced by the way in which deforestation is defined the final section of the chapter examines this matter and suggests the need to widen the usual definition, which requires forest clearance to encompass less severe human impacts.

Humid tropical environments

Climate and vegetation

The humid tropics forms a belt straddling the Equator that has high rainfall and moderately high temperatures throughout the year. The high rainfall, generally averaging 1,800 to 4,000 mm per annum and at least 1,200 mm, results from the ascent of warm moist air due to thermal convection and the meeting of the two sets of Trade Winds that flow towards the Equator from subtropical latitudes (30–40°N and S). The fairly even distribution of solar radiation during the year leads to constant high temperatures with little variation: mean monthly temperatures are generally 24–28°C and it never freezes.

The humid tropics extends over parts of the continents of Central and South America, Africa, Asia and Australia as well as islands in the South China Sea and Pacific Ocean. But it is only part of the wider tropical region located between the Tropics of Cancer and Capricorn (latitudes 23°N and 23°S respectively) and which includes dry as well as wet areas. Moving north and south from the Equator the climate becomes drier and more seasonal with increasing latitude, culminating in the two great desert belts that dominate subtropical latitudes where air flowing from the Equator eventually subsides, making rainfall formation difficult.

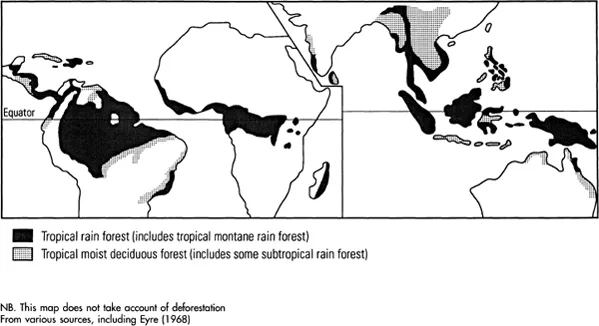

Nor is the humid tropics a homogeneous region. The simplest division is into permanently humid and seasonal zones. Tropical rain forest is found in the permanently humid tropics, the zone generally close to the Equator in which rainfall is distributed fairly uniformly throughout the year (Figure 1.1). The seasonal humid tropics may receive the same (or even more) annual rainfall but have a distinct dry season (60 mm of rainfall per month or less) that promotes the growth of tropical moist deciduous forest. This has a prominent component of leaf-shedding deciduous trees and is also known as ‘monsoon forest’, owing to the link in Asia in particular between rainfall seasonality and monsoon winds. Tropical rain forest and monsoon forest both owe their names to the German botanist Schimper (1898,1903).

Soils

A long history of weathering and leaching has left soils in the humid tropics generally deep and devoid of nutrients. This may seem paradoxical given the profuse vegetation, but often a large proportion of nutrients in the ecosystem are contained in the vegetation rather than the soil1. Most tropical soils are deficient in phosphorus and susceptible in varying degrees to compaction, crusting and erosion (see Chapter 6). But not all soils are infertile, for there are small but significant areas of fertile soils, such as the alluvial and volcanic soils, that can support highly productive agriculture.

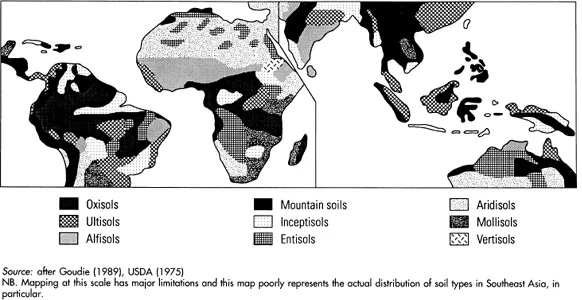

The world distribution of different types of soil is mapped using global classification systems such as the one devised by the US Department of Agriculture (USDA, 1975). This splits the world’s soils into ten major types, or orders, based on key soil characteristics (Table 1.1). Seven of the orders are found in the humid tropics but 63 per cent of the total land area is occupied by just two of them, the low fertility oxisols and ultisols (Figure 1.2) (Sanchez, 1976,1981).

Figure 1.1 Distribution of tropical moist forest

Table 1.1. Tropical soils classified using the USDA soil taxonomy

| Order | Sub-orders | Characteristics |

Orders present in the humid tropics |

| Entisols | Aquent, fluvent, psamment | Immature, usually azonal |

| Inceptisols | Andept, aquept, tropept | Moderately developed |

| Alfisols | Aqualf, udalf | Moderate to high base content |

| Ultisols | Aqult, humult, udult | Low organic matter, low base supply |

| Oxisols | Aquox, humox, orthox | Nutrient poor, high in iron and aluminium, deeply weathered |

| Spodosols | Aquod, ferrod, humod, orthod | Accumulation of iron and aluminium oxides and/or organic matter under light sandy layer, podzols |

| Histosols | fibrist, folist, hemist, saprist | Peaty soils |

Orders not present in the humid tropics |

| Aridisols | – | Desert and semi-desert soils |

| Mollisols | – | Temperate grassland soils |

Vertisols | – | Cracking clay soils with turbulence in profile |

NB. Orders absent from humid tropics are not differentiated into sub-orders Source: Goudie (1989), USDA (1975)

The oxisols and ultisols are red and red/yellow soils respectively, highly acidic, lacking in major plant nutrients, and with an excess of aluminium and manganese. Most soil nutrients are associated with soil organic matter, which is less abundant in ultisols than in oxisols. Ultisols are also more vulnerable to erosion when vegetation is removed. Oxisols are better drained but more susceptible to the formation of iron-rich subsoil concretions, called laterite, which restrict root growth. If these are exposed by soil erosion a hard brick-like covering can form on the surface, but contrary to earlier expectations laterization threatens only a small proportion of all soils in the humid tropics, mostly in seasonal areas (Moorman and Van Wambeke, 1978). Oxisols and ultisols can be made more productive by adding lime (to reduce acidity) and nitrogen and phosphorus fertilizers. But these are expensive inputs for small farmers, need skilled application, and so are not usually a practical option at the moment.

Figure 1.2 Distribution of soil orders in the tropics, according to the USDA Soil Taxonomy (Seventh Approximation)

The alfisols, richer in basic nutrients, are the next most common soil order but occur mainly in seasonal areas. Four other orders, the entisols, inceptisols, histosols (peaty soils) and spodosols (low fertility podzols) are found in more specialized environments, such as those close to rivers and on lands receiving regular inputs of volcanic ash. The andepts, a sub-order of the inceptisols formed from volcanic ash, are highly fertile and provide the basis for highly productive farming on the islands of Java, Bali and Sumatra (Indonesia) and Mindanao and Luzon (the Philippines). Older alluvial soils are also a type of inceptisol (aquepts) and distinguished from recently deposited alluvial soils classed as entisols (fluvents). Mountain soils are not easily classified by this scheme because soil type changes markedly with altitude.

Types of tropical moist forests

The tropics as a whole contains two main types of forests: closed forests, such as tropical rain forest and tropical moist deciduous forest, with a high density of trees and a closed canopy, and open forests, such as the savanna woodlands of the dry tropics in which trees are scattered at low density over grasslands. Closed forests do occur in the dry tropics but the majority are in the humid tropics. Tropical moist forests are mainly broad-leaved but small areas of coniferous (needle-leaved) and bamboo forests are found too. There are at least fourteen different types of tropical rain forest ecosystems (Whitmore, 1984,1990), conveniently grouped here as dryland, wetland and montane rain forests (Table 1.2), as well as various types of tropical moist deciduous forest.

Forests are not the natural vegetation everywhere in the humid tropics, however. Savanna grasslands are found where soil conditions (poor drainage or nutrient content, a subsurface hardpan, etc.) are inhospitable to tree growth (Cole, 1986). They also occur in areas in Africa and elsewhere with a long history of clearance and burning for hunting and grazing. Asia has large areas of weedy grasslands (e.g. Imperata spp.) on sites where overcultivation and frequent burning by shifting cultivators has allowed them to become dominant.

Table 1.2. Types of tropical moist forest ecosystems

| Site type | Forest type | Specific site/ciimate requirements |

| Dryland | Lowland evergreen rain forest | Everwet climate |

| | Lowland semi-evergreen rain forest | Short dry season |

| | Moist deciduous forests

(various types) | Pronounced dry season |

| | Heath forest | Podzolized sandy soils |

| | Limestone forest | Over limestone |

| Ultrabasic forest

| Over ultrabasic rocks

|

| Wetland | Freshwater swamp forest | |

| | Permanent swamp forest | Permanently wet |

| | Seasonal swamp forest | Periodically wet |

| Peat swamp forest

| Coastal or inland

|

| | Saltwater swamp forest | |

| | Mangrove forest | Coastal |

| | Brackish water swamp forest | Coastal |

| Beach forest

| Coastal

|

| Montane | Lower montane rain forest | From 700mWM. 1500mNG |

| | Upper montane rain forest | From 1500mWM, 3000mNG |

| Subalpine forest | From 3000–3500m to treeline |

NB. WM indicates approximate transition altitude in West Malesia, NG in New Guinea.

Source: adapted from Whitmore (1990)

Dryland rainforests

The group of dryland (as opposed to wetland or swamp) forests includes the richest of all tropical rain forest ecosystems: tropical lowland evergreen rain forest. This has the greatest height, biomass and species diversity and is fully evergreen. The closed canopy is 20–40 m high, and larger trees (called ‘emergents’) pierce the canopy to reach heights of 50 m.

The trunks of emergent trees often have huge buttresses (up to 7.5 m high), probably to provide additional mechanical support since the roots are quite shallow. Tree leaves are leathery to reduce moisture loss in the canopy and nutrient leaching by rainwater, and have pointed ‘drip tips’ to help water drain away quickly as a fine mist (thought to reduce splash erosion of soil when the droplets reach the ground). There are many herbaceous or woody climbing plants, rooting in the ground and growing as high as canopy trees but using trees for mechanical support. Orchids and other epiphytes also attach themselves to tree branches, either above or just below the rain forest canopy, and give the canopy a multi-coloured appearance. They do not root in the ground but coll...