- 286 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

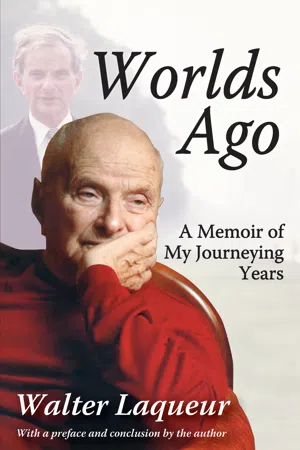

Originally published in 1993, Worlds Ago is not only about the politics of the times, but also about the world into which Walter Laqueur was born and raised and the world that shaped him: pre-war Germany in 1921, where he witnessed the rise of the Nazi party. It is a story of families, friendships, and early love; achievements and disappointments; and facing and surviving dangerous circumstances in which many of those close to him lost their lives. It was a world where calm seas and waters were rare and survivors were lucky to escape the engines of war.This memoir further recounts his experience as an agricultural laborer on a kibbutz, in what was Palestine at the time, living among Bedouin and Arab herdsmen, sharing their labor and lifestyle. Laqueur became a journalist and writer in his twenties, and witnessed dramatic events in the Middle East and the emergence of Israel in the aftermath of World War II. He came to know many of the leading figures on both sides who were involved in the establishment of the State of Israel. Walter Laqueur went on to become one of the leading historians and interpreters of the Weimar period in Germany. This new edition, revised to tell his story up until 1948, also includes a new preface and conclusion.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Worlds Ago by Walter Laqueur in PDF and/or ePUB format. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

eBook ISBN

9781351470971Subtopic

World HistoryPart One

A German Childhood

1

Childhood

I was born on Thursday, May 26, 1921, the only child of not-very-young parents. My father worked in town or traveled, my mother spent most of the time with me. We had a small apartment in a southern suburb of Breslau, Schwerinstrasse 64, third floor, right entrance. In my early memories, the apartment and the house figure prominently. There was a balcony in front, and one in the back, with geraniums grown in front and tomatoes in the rear. There is a photograph taken on my fifth birthday in which I am critically mustering the presents, which include a tennis racket (my interest in sports goes back to an early date). I was dressed in a then-fashionable sailor suit, with high shoes, well over the ankles. My parents were serious people, but on this occasion they had engaged in a practical joke. I loved cherries more than anything else; my father on one occasion wrote a poem on the subject. Thus, my parents had put a few cherries on top of the tomato plants, arguing that in my honor, and in recognition of good behavior, the plants had produced cherries. I did not believe their story.

Once I began to explore our apartment I found the telephone an object of great fascination. These were the pre-direct-dial days and one got a connection by way of lifting the receiver and operating a handle, whereupon the lady at the central telephone exchange would answer and provide a connection. Of even greater fascination was the radio. We had a little crystal set, also called a detector set, with headphones. Reception was indifferent and limited to the local station. It was by means of the little radio that I came to know the hit songs of 1926 and 1927, and many of them I remember today; the late twenties were the golden age of the Schlager (pop tunes), even more so in Germany than in the United States. My father did not read much and probably never went to a museum, but he was a man of considerable musical culture, and my lowbrow taste and whistling “Oh, Donna Clara” and “Valencia” must have pained him, but he did not try to influence me until much later.

My parents did not have many books; I do remember a two-volume encyclopedia published in 1880 or thereabouts, from which I got my first political (and sexual) knowledge as well as much other useful infromation. But there was much sheet music, and occasionally father and mother would play the piano. I liked best the adaptation for piano of the classical operas and operettas and so did they. I grew up with Leporello and Count Almaviva, with Papageno and “La donna è mobile,” even though I could not possibly understand at the time their reflection on love, jealousy, and the war of the sexes. I knew considerable stretches of Freischütz and Martha as well as the Fledermaus by heart well before I had ever read a serious book. I could whistle the Si j’étais roi over-ture and arias from operas by Rossini, Lortzing, and Boieldieu, not to mention Alessandro Stradella; the Postillon de Longjumeau and other opéras comiques by Adam that are seldom, if ever, performed today were among my favorites. In my father’s generation such knowledge was commonplace. In the 1950s, in London, I became friendly with Robert Weltsch, the distinguished editor who had grown up in Prague before 1914, a contemporary of Kafka and Werfel. His knowledge of opera and operettas was far more profound than mine, if only because it included Wagner, whom I did not like except for the Meistersinger. In my generation, alas, such interest was no longer part of Allgemeinbildung (general education), except among professionals and experts. True, during the last two decades there seems to have been a revival of interest in classical music among the young, but by and large the one culture of 1900 has become two, three, or more cultures.

My parents were not well off. Most of my friends had more—and more elaborate toys. I was deprived, for instance, of an electrical railway, but I remember always having had a football I also got a bicycle early on. Not a new one, of course, but a sturdy NSU, which almost certainly predated World War I. It even had three gears, which aroused general curiosity, for at that time bicycles with gears had gone out of fashion—not to come back until recent years. Even though my family was not well-to-do, they had live-in help, usually countrywomen from Upper Silesia. Some stayed for a short time, others for years. I remember Anna, tiny, good-humored, simpleminded, in her fifties; she had lost two fingers in an accident. The main meal, as customary then, was lunch and there were always three courses. I was a great devotee of beefburgers, called German beefsteaks in those parts. My mother attempted to induce me to eat fish; she probably tried too hard, because I strictly refused to touch it until many decades later, when I became a fish addict. My grandson shares my predilection for beefburgers and my former aversion to fish, though his parents, who believe in progressive education, have never compelled him. Perhaps there is something in genetics after all. Evenings we had a sandwich or two; on fine summer days the table was set on the front balcony. Food was well prepared, but wine was drunk only on holidays. To clear one’s plate was imperative. This had to do with the war and inflation, when food had been rationed and very scarce, but also the general Prussian ethos.

I do not remember when I first received pocket money, but it must have been very little and for this reason, if for no other, the visit of an uncle or some other relation was a welcome event. It invariably meant a present—one mark, or even two or three. I do not want to sound virtuous but from an early age I spent my pocket money on books—not, alas, Kant and Goethe, but adventure stories of the Karl May variety, immensely popular in Germany from the turn of the century to the present day. Some books allegedly written by Karl May continue to appear even now, eighty years after his death. Fifteen years ago an attempt was made to acquaint American readers with Winnetou and Old Shatterhand, the Indian chief and the eminent trapper, the main heroes of this unending series. I did my share by favorably reviewing them in the New York Times. The books were a total failure.

Certain events in my early childhood stand out in my memory more vividly than others. I must have been five or six when I had pneumonia and a high fever. I remember Dr. Weigert, our physician, by my bed prescribing very unpleasant cold compresses. My father seemed even more serious than usual; only later was I told that his mother had died the very same day. Then a little later, lying quietly in bed with the curtains drawn, I observed moving shadows on the ceiling—reflections of the cars and horse carts passing in the streets. These reflections have remained a mystery to me to this day. My scientific understanding was never really developed.

These were the prepenicillin days, and the diseases of infancy were taken seriously—a week or two in bed after a flu was the rule. Each winter I suffered from unending colds, and the doctors could do little but paint the throat with iodine, a most unpleasant experience, which helped not at all. At the age of five or six I had part of my tonsils removed, which hurt very badly; the old-fashioned kind of anesthesia with a suffocating mask put on one’s face remained a trauma for many years. My parents told me that Amanullah, the then king of Afghanistan, underwent the same operation the very same day. But this did not comfort me at all. The doctor prescribed ice cream from the nearby Gelateria Italiana and this had a better effect.

The apartment was small; the house, on the other hand, was big, with a sizable courtyard, where carpets were cleaned with much noise and linen was dried. On the floor below lived a little girl, my friend Helga; still farther below, a strange elderly couple named Lichtenstein. He was the editor of a spiritualist or astrological journal. I had no idea what it meant. Ours was a corner house; one could enter and leave it from two streets.

Schwerinstrasse was purely residential, but there were shops around the corner in Opitzstrasse, named after a seventeenth-century pioneer of German poetry. Frequently, I went shopping there with my mother at a stationery shop full of interesting things such as colored picture sheets and fancy pencils. It was run by an elderly lady who did not like loitering little boys with no money to spend. Then there was Matuszewski’s, the drugstore and perfumery, a great favorite because it had all kinds of samples to give away, such as Krugerol cough drops. I liked these very much, another curious predilection shared by my grandson Benjamin. A corner away there was the Konsumverein, the cooperative food store. I was sent there on my first purchasing missions to buy bread, which came by weight—usually three pounds or four. Nearby was a large (“Pomeranian”) dairy; I still remember the notice in the window advertising their FOUR-FRUIT MARMALADE— 10 PFENNIG ONLY. It was the cheapest they offered, but I could not get enough of this delicacy. In front of the dairy there was a taxi stand; if I remember correctly there were also horse-driven carriages, which I found more interesting. But they disappeared one by one. A taxi ride was a rare luxury, and I cannot remember more than one or two such occasions in my childhood. Usually, one went by electrical tramway, slow but reliable, which passed every five or ten minutes. There were also a few buses, but they went crosstown, not to the city center, and we used them less frequently.

I have not yet mentioned the two shops that greatly intrigued me when I was a little older—the travel agent’s and the newsstand. The moment I could read, at the age of six, there was nothing that interested me more than travel prospectuses and atlases. In the beginning I went with my mother to the travel agent’s, and following my instructions, she asked for timetables and leaflets for faraway, exotic countries. When she refused to ask for this literature as often as I wanted, I went alone, and the employees, more than slightly amused, gave me all their illustrated booklets about Las Palmas, Colombo, Luxor. My first essay dates back to my sixth or seventh year. It was written for my father’s birthday and read as follows: “Last month I went to Bangalore and shot a tiger.” There was also a drawing of a person, a rifle, and an animal sitting in a tree. How did I know about the capital of the state of Mysore, west of Madras? Whatever the source of my knowledge, I knew a great deal about cities in India, China, and Latin America—how many people lived there and even what they did for a living. My interest in geography certainly predated my interest in history. I don’t think I saw a black person or an Oriental until many years later, except perhaps in the movies, but in my fantasies I had always mixed with them.

Geography meant adventure, faraway countries, the discovery of the unknown. I was six when Lindbergh’s Spirit of St. Louis landed in Paris, and I remember reading the headlines in front of the newspaper stand. The owner took a dim view of little boys trying to bend the papers displayed in good order in front of the shop, let alone opening them and generally blocking access to the kiosk window, but I was impervious to threats. On Sunday mornings my father sent me to buy the Berliner Tageblatt, the leading paper at that time, mainly because it had a music supplement; I remember his excitement when I brought him Prokofiev’s Love for Three Oranges. Again, why should I remember it? Because I loved oranges or because the title struck me as perfectly idiotic? The winter 1928-29 was the coldest on record, some days the temperature going down to minus 30 degrees centigrade (- 22°F), and for once my parents were genuinely worried whenever I did not return from the kiosk in good time. Apparently I had discovered something of such interest in the papers that, oblivious of the cold and the snowstorm, I had to finish the story, no matter how freezing it was outside.

Lindbergh was not my only hero, another was Umberto Nobile, who, in an airship he had constructed, was the first to fly over the North Pole. But the real excitement came two years later when his expedition got stranded in the Arctic region. Lindbergh was then the symbol of the spirit of independence and of freedom, whereas Nobile was a Fascist general. Who could have known that the one would end up as an advocate for Nazi Germany and the other as a Communist deputy in the Italian parliament? But nazism and communism were far away in 1928, at least for the boy glued to the newsstand. When I became a customer a few years later, I bought the Monday morning sports paper, not the party political press.

There were a lot of small parks in our neighborhood where mothers took their children for a walk. It must have been on one of these walks that I saw my first zeppelin. I don’t know which model it was, for about a hundred in all had been constructed. But it seemed (and was) enormous, effortless, majestically gliding through the blue skies, much more impressive than the small planes almost daily painting the heavens with advertisements for Persil and other washing powders.

There was also the Sauerbrunnen, a little lake with a source of mineral water, and a lot of horse-chestnut trees in all directions. We children collected the red-brown conkers and the acorns and made all kind of toys from them.

Many years later I learned from the writings of learned film critics that the street in the Weimar Republic was something threatening and hostile, best to be avoided. The street meant danger; security was at home. They must have been watching other streets; those I knew seemed a perfectly neutral playing ground. At home it often was boring; the action was in the street. The street gangs assembled there, but they were not particularly violent, rather more or less accidental gatherings; their composition would change from week to week.

Not far from us there was an open stretch of land, deserted building sites and lots. In autumn we dug up occasional potatoes and roasted them; in winter many of the abandoned building sites were filled with water, and we constructed little floats to cross them. Better yet, if the temperature got below freezing, we ventured on the ice, disregarding all warnings. We believed that if one ran over the ice fast enough, it would not break, and my personal experience bore out this utterly wrong assumption. I was strong for my age and fast, but not good at skating and skiing, probably because I did not persevere, giving up after my first failures.

There was one sinister street and it took some daring to cross it: This was Krullstrasse in the center of town, a curved thoroughfare of shabby houses, the street of the prostitutes. I had only a vague idea what a prostitute did for a living, but we were told that the ugly women walking the street would snatch our caps; since I never had a cap or hat, the danger was minimal. But even the guidebook to Breslau said that this street was not to be frequented in darkness. So this was “Sinister Street.”

I cannot remember that my father ever took a holiday. Apparently business was slack, and he could not afford to abandon it. Usually, I went with my mother to the Riesengebirge (the Giant Mountains) in summer and also in winter. These were not the Himalayas, as the highest peak was a mere 5,000 feet above sea level, but to a boy the elevation seemed giant indeed. The border between Germany and Czechoslovakia ran on the very ridge of the mountains; until 1933 we usually went to the German side, but after the Nazis came to power we always stayed in Czech resorts, a few miles beyond the border. Other families traveled to more distant places, the Baltic, the North Sea, or even Switzerland and the Dalmatian coast. But again, if there was a feeling of deprivation it did not run very deeply.

There was so much of interest even in the small Silesian resorts, such as the impoverished Russian grand duke in our hôtel garni who always kept to himself and did not even answer questions at the table d’hôte. There was the fascination of picking blueberries and mushrooms with Mother, who, being a country girl, knew a great deal about the subject. There were sunny clearings and the silent darkness of the forest, little waterfalls and all kinds of wild animals. Sometimes we would stay in a Baude, a wooden country inn high in the mountains, far away from the crowds and often lacking some of the basic amenities. The train from Breslau arrived in winter in the early evening at the little station; a horse-drawn sleigh was waiting and would take us and our baggage through the snow-covered forests. It was cold, but there were heavy blankets to cover us. The horses had little bells fastened to their harnesses. These drives were one of the high points of the holiday. When I read Eichendorff and other German Romantic poets or when I listen to Schumann or Mendelssohn, driving or walking through the silent, snow-covered forest in the dark is the mental image that immediately comes to mind.

If I had the gifts of a poet, this would be the right place for a rhapsody dedicated to the forest. One of the few professions I seriously considered as a boy was that of a forester; I loved the sea but I never envisaged being a sailor. After a bad night, there is nothing to restore the spirits like breathing the air of Rock Creek Park from the balcony of my Washington, D.C., home. I spent my holidays in the forest first with my mother, later with my peers in our youth group, and later still, when I worked in a factory, I regularly toured the Silesian mountains. In our youth group new members had to pass a test of courage: They were led blindfold into the middle of a forest and then abandoned, having to find their own way back to civilization. I had many fears, but that of the forests of the night was never among them. I revisited the forests of my youth some fifteen years after the end of the war, and they seemed unchanged. But in fact, they were diseased and today they are quite dead, killed by the fumes from the chemical works on both sides of the border. It is a tragic story and the full extent of the disaster I realized only after having read the moving account of Ota Filip, a leading Czech writer, who had been to Klein Aupa, the small village on the Czech side of the frontier where I had spent so many happy hours as a child and adolescent. The mountains were denuded, he reported, and his pictures confirmed the sad story. It was the end not only of a lovely landscape and tourism but of the village. True, they were now experimenting with mountain ash and Siberian birch trees; perhaps they would prove to be more resistant. But it will never be the same again.

At the age of twelve I went through a mildly rebellious phase and ceased to travel with my mother. Instead, I went on excursions with a group of boys my own age. But this belongs to another chapter.

I have not written about friends, and I don’t think I had many. The fact that I was an only child did not help. I went to kindergarten but I remember nothing about it, except that I was told on occasion by my mother that I was aggressive and moody, and that I had difficulties getting along with other children. She was a good and kind woman but given to exaggeration; in this specific case she was no doubt right, for the years from age five to nine were difficult ones for me. I was head-strong, prickly, and occasionally had a foul temper. I recently looked at some old photographs; perhaps my imagination unduly influences photo interpretation, but if so, not by very much. At five I had been a pretty child; at eight and nine I appear awkward, introverted, defiant, obstinate. When we visited some wealthy acquaintances, I deliberately smashed a Gartenzwerg, a garden gnome, because, for one reason or another, I had been frustrated. Since it was a valuable gnome, there was much indignation and I received a fitting punishment. I also played a leading role in causing mayhem at birthday parties. Nor were my first years in school altogether happy ones. I was sent to a private school of considerable reputation, called Zawadzki, or von Zawadzki. I did not do badly; in fact, it was suggested to my parents that I should skip a year, so that at the age of seven I found myself in the company of boys and girls aged eight or even nine, a considerable difference at that age. My handwriting was not too good, and I had difficulties with some other subjects.

There must have been other reasons for my unhappiness. Most of the other children came from wealthy families, and some were the offspring of the aristocracy. There was some snobbishness, real or imaginary; sometimes they did not want me at their games. Thus I was, or felt, a bit of an outsider and, while I cann...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface to the Transaction Edition

- Preface

- Part One: A German Childhood

- Part Two: Young Man Adrift: Palestine in Peace and War

- Conclusion to the Transaction Edition

- Index