eBook - ePub

The Science of Expertise

Behavioral, Neural, and Genetic Approaches to Complex Skill

- 468 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Science of Expertise

Behavioral, Neural, and Genetic Approaches to Complex Skill

About this book

Offering the broadest review of psychological perspectives on human expertise to date, this volume covers behavioral, computational, neural, and genetic approaches to understanding complex skill. The chapters show how performance in music, the arts, sports, games, medicine, and other domains reflects basic traits such as personality and intelligence, as well as knowledge and skills acquired through training. In doing so, this book moves the field of expertise beyond the duality of "nature vs. nurture" toward an integrative understanding of complex skill. This book is an invaluable resource for researchers and students interested in expertise, and for professionals seeking current reviews of psychological research on expertise.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Science of Expertise by David Z. Hambrick, Guillermo Campitelli, Brooke N. Macnamara, David Z. Hambrick,Guillermo Campitelli,Brooke N. Macnamara in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Business Education. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

p.1

1

INTRODUCTION

A Brief History of the Science of Expertise and Overview of the Book

David Z. Hambrick, Guillermo Campitelli, and Brooke N. Macnamara

The Science of Expertise: A Brief History

Nearly everyone has witnessed a display of complex skill that is so extraordinary— so far outside the normal range of human capabilities—that it defies belief. The 1968 Olympics in Mexico City were witness to arguably the greatest athletic feat of all time, when Bob Beamon won the gold medal in the long jump with a leap of 29 feet 2¼ inches. In an event usually won by a few inches, Beamon bettered silver medalist Klaus Beer by a bewildering 28 inches. Nearly a half-century later, his Olympic record still stands. More recently, the world watched as 60-year old Diana Nyad swam the 110 miles between Havana, Cuba, and Key West, Florida. Performances of prodigies are especially memorable for their seeming otherworldliness, as when the pianist Evgeny Kissin made his debut with the Moscow Philharmonic Orchestra at the age of 12, and when 13-year-old Magnus Carlsen famously played chess World No. 1 Garry Kasparov to a draw. We also admire extraordinary skill in everyday life—the master mechanic for uncanny ability to diagnose and fix what ails our automobiles, the surgeon for acumen in removing disease with surgical instruments without harming the patient, the potter who transforms lumps of clay into elegant bowls, the pilot who deftly lands a jumbo jet in bad weather, and so on.

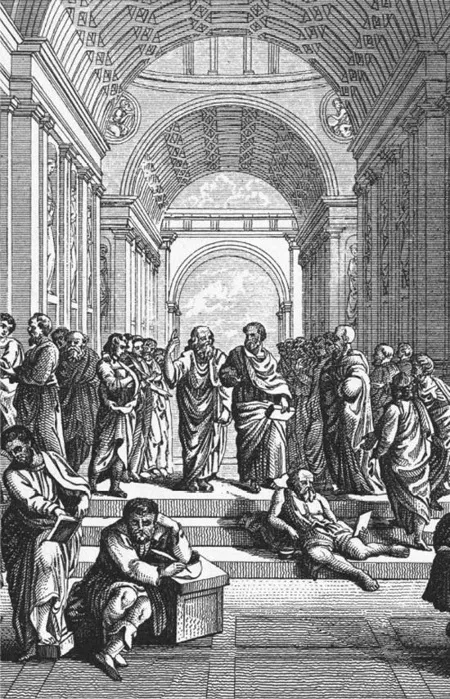

What is the origin of individual differences in expertise? This is a central question for the science of expertise, and the major focus of this book. Given that individual differences in skill are so obvious through casual observation, it may also be one of humankind’s earliest existential questions. Consider that in prehistoric art we see what may well have been celebration of exceptional performance: Paintings up to 20,000 years old in the Lascaux cave in France include images of wrestlers and sprinters, and in the Cave of Swimmers in present-day Egypt, depictions of archers and swimmers date to 6000 B.C.E. Several thousand years later, the Ancient Greeks laid the foundation for the contemporary debate over the origins of expertise. In The Republic (ca. 380 B.C.E.), Plato made the innatist argument that “no two persons are born alike but each differs from the other in individual endowments.” Aristotle, Plato’s student who is often regarded as the “first empiricist,” countered that experience is the ultimate source of knowledge. These differing philosophies are symbolized in the fresco School of Athens (1509–1511) by the Italian Renaissance artist Raphael (Figure 1.1). Plato and Aristotle are pictured in the center of the fresco; each holds a book in his left hand and gestures with his right—Plato upward to the heavens and Aristotle outward to the concrete world.

p.2

FIGURE 1.1 Raphael. The School of Athens. Detail from 1873 illustration of the fresco (1510–1512), which is in the Vatican. Image credit: bauhaus1000.

p.3

What might be considered the first scientific study of expertise was published in 1835 by the Ghent-born statistician and sociologist Adolphe Quetelet (see Simonton, 2016), who introduced the normal curve to describe individual differences. Using archival data, Quetelet documented that output in famous French and English dramatists peaked at about age 50. Some 35 years later, making use of Quetelet’s statistical work, Francis Galton (1869) published his groundbreaking volume Hereditary Genius. Galton’s major question was whether intellectual ability is heritable in the same way that his half-cousin Charles Darwin had argued that physical characteristics of creatures such as the size and length of birds’ beaks are heritable. There were no standardized tests of intelligence in the mid-1800s, so Galton scoured Who’s Who-type biographical dictionaries and used reputation as a proxy for ability. Galton discovered that, within a given field, eminent individuals tended to be biologically related more than would be expected by chance. For example, he noted that there were more than 20 eminent musicians in the Bach family—Johann Sebastian being just the most famous—and he observed that the Bernoulli family “comprised an extraordinary number of eminent mathematicians and men of science.” Galton concluded that genius arises almost inevitably from “natural ability.”

Galton’s (1869) book created a stir. The Swiss botanist Alphonse Pyrame de Candolle (1873) conducted his own biographical study and found that some countries produced more scientists than others, taking population into account. For example, his native Switzerland produced over 10 percent of the scientists in his sample, but accounted for less than 1 percent of the European population. De Candolle concluded that environmental factors—or what he called “causes favorables”—were the primary antecedents of eminence (Fancher, 1983). In a similar vein, Edward Thorndike (1912), the father of educational psychology, claimed that “when one sets oneself zealously to improve any ability, the amount gained is astonishing” and added that “we stay far below our own possibilities in almost everything we do . . . not because proper practice would not improve us further, but because we do not take the training or because we take it with too little zeal” (p. 108). John Watson (1930) added that “practicing more intensively than others . . . is probably the most reasonable explanation we have today not only for success in any line, but even for genius” (p. 212).

Thus, from antiquity on, the pendulum has swung between the view that experts are “born” and the view that they are “made.” In psychology, the experts-are-made view has dominated the scientific study of expertise for the better part of 50 years. Building on earlier work by de Groot (1946/1978), Chase and Simon (1973) had participants representing three levels of chess skill (novice, intermediate, and master) view and attempt to recreate arrangements of chess positions that were either plausible game positions or random. The major finding was that chess skill facilitated recall of the game positions, but not the random positions. Thus, Chase and Simon concluded that the primary factor underlying chess skill is not superior short-term memory capacity, but a large “vocabulary” of game positions. More generally, they argued that although “there clearly must be a set of specific aptitudes . . . that together comprise a talent for chess, individual differences in such aptitudes are largely overshadowed by immense differences in chess experience. Hence, the overriding factor in chess skill is practice” (Chase & Simon, 1973, p. 279).

p.4

Subsequent research showed just how powerful the effects of training on performance can be. As a particularly striking example, Ericsson, Chase, and Faloon (1980) reported a case study of a college student (S.F.), who through more than 230 hours of practice, increased the number of random digits he could recall from a typical 7 to a world record 79 digits. (Today, the world record for random digit memorization is an astounding 456 digits.) Verbal reports revealed that S.F., a collegiate track runner, accomplished this feat by recoding sequences of digits as running times, ages, or dates, and encoding the groupings into long-term memory retrieval structures. For example, he remembered 3596 as “3 minutes, 59.6 seconds, fast 1-mile time.” Ericsson et al. concluded that there is “seemingly no limit to improvement in memory skill with practice” (1980, p. 1182).

The consensus that emerged from all this research was that expertise reflects acquired characteristics (nurture), with essentially no important role for genetic factors (nature). This environmentalist view reached its apogee in the early 1990s, with publication of Ericsson, Krampe, and Tesch-Römer’s (1993) seminal article on “deliberate practice.” In a pair of studies, Ericsson et al. found positive correlations between estimated amount of deliberate practice (practice alone) and skill level in music. The most skilled musicians had accumulated thousands of hours more deliberate practice than their less accomplished counterparts. In the spirit of Watson (1930), Ericsson et al. concluded that “high levels of deliberate practice are necessary to attain expert level performance” (Ericsson et al., p. 392) and explained that their “account does not depend on scarcity of innate ability (talent)” (Ericsson et al., p. 392). Another important event was the publication of the field’s first handbook—the 900-page Cambridge Handbook on Expertise and Expert Performance (Ericsson, Charness, Feltovich, & Hoffman, 2006). Though this volume was a valuable resource for the field, it seems fair to say that the focus was overwhelmingly on experiential determinants of expertise (i.e. practice/training). There are, for example, 102 index entries for “deliberate practice” and “training,” compared to 12 for “talent” and “genetics.”

There was, however, growing dissent in the literature. Simonton (1999), one of the most eloquent commentators, acknowledged that “it is extremely likely that environmental factors, including deliberate practice, account for far more variance in performance than does innate capacity in every salient talent domain” (p. 454), but continued: “Even so, psychology must endeavor to identify all of the significant causal factors behind exceptional performance rather than merely rest content with whatever factor happens to account for the most variance” (p. 454). In a similar vein, Gagné (1999) argued that there is “[n]o doubt that the single most important source of individual differences in the case of SYSDEV [systematically developed] abilities is the amount of LTP [learning, training, and practice]. But . . . genetic endowment is also a significant, albeit indirect, cause of individual differences in these abilities.”

p.5

Dissent grew into empirical challenge in the mid-2000s—which, coincidentally or not, was around the time the environmentalist view was popularized in books such as Malcolm Gladwell’s (2008) bestseller Outliers: The Story of Success and Geoff Colvin’s (2010) Talent is Overrated: What Really Separates World-Class Performers from Everybody Else. In one of the first direct tests of the deliberate practice view, Gobet and Campitelli (2007) found that there was massive variability in the amount of deliberate practice required for chess players to reach “master” status—from about 3,000 hours to over 23,000 hours. The implication of this finding was that factors other than deliberate practice must also play an important role in becoming highly skilled in chess.

Subsequently, the three of us (with numerous colleagues around the world) published a series of papers demonstrating that deliberate practice is an important piece of the expertise puzzle, just not the only important piece. As one example, Meinz and Hambrick (2010) found that working memory capacity, which is known to be substantially heritable, added to the prediction of individual differences in piano s...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- The Science of Expertise

- Frontiers of Cognitive Psychology

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Introduction: A Brief History of the Science of Expertise and Overview of the Book

- Part I Behavioral Approach

- Part II Neural Approach

- Part III Genetic Approach

- Part IV Integrative Models

- Part V Perspectives

- Index