eBook - ePub

Mining and the Environment

International Perspectives on Public Policy

- 180 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

For centuries, denuded landscapes, fouled streams, and dirty air were accepted by society as part of the price that had to be paid for mineral production. Even initial environmental legislation devised by industrialized countries in the 1960s and 1970s was largely designed without mining in mind. And developing countries had little in the way of environmental policy. With the advent of sustainability in the 1990s, times have changed. Today's economic development, many now feel, must not come at the expense of an environmentally degraded future. Current policies toward mining are under rigorous review, and mineral-rich developing countries are designing environmental policies where none existed before. In Mining and the Environment, noted analysts offer viewpoints from Australia, Chile, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the European community on issues and challenges of metal mining.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mining and the Environment by Roderick G. Eggert in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Ecology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

The Limitations of Environmental Regulation in Mining

ALYSON WARHURST

Public policy to promote technical change and foster economic efficiency, in addition to environmental regulation, is most likely to contribute towards sustained and competitive improvement in the long-term environmental management of nonrenewable natural resources. Three main issues are analysed in this lecture, drawing out implications for the different contexts of both industrialised and developing countries.

The first issue is the relationship between production efficiency and environmental performance. There is growing evidence that technical change, stimulated by the ‘Environmental Imperative’, is reducing both production and environmental costs to the advantage of those dynamic firms that have the competence and resources to innovate. Such firms include mining enterprises in developing countries as well as transnational firms, but the evidence is strongest for large new investment projects and greenfield sites. In older, ongoing operations, environmental performance correlates closely with production efficiency. Environmental degradation is greatest in operations working with obsolete technology, limited capital, and poor human resource management. Policy to promote the development of the technological and managerial capabilities to effect technical change in those organisations would lead to improved efficiencies in the use of energy and chemical reagents and in waste disposal; to higher metal recovery levels; and to better workplace health and safety. This in turn would result in improved overall environmental management.

The second issue is the economic and environmental limitations of regulation. Currently, the environmental performance of a mining enterprise is more closely related to its capacity to innovate than to the regulatory regime within which it operates. Although international standards and stricter environmental regulation may not pose problems for the economics of new mineral projects, there could be significant costs involved for older, and particularly inefficient, ongoing operations. Controlling pollution problems in many of these cases requires costly add-on solutions: water treatment plants, strengthening and rebuilding tailings dams, scrubbers and dust precipitators, etc. Furthermore, in the absence of technological and managerial capabilities, there is no guarantee that such items of pollution control—environmental hardware— will be incorporated or operated effectively in the production process. In some instances, such requirements are leading to shutdowns, delays, and cancellations, as well as reduced competitiveness. When mines and facilities are shut down, the cleanup costs frequently get transferred to the public sector, which—particularly in developing countries—has neither the resources nor technical capacity to deal with the problem effectively.1

The third main issue is the case for an environmental management policy. The implication of this analysis is that to ensure competitive and sustainable environmental management practices in metals production, governments need to embrace public policy that goes beyond traditional, incremental, and punitive environmental regulation. The latter, in the old ‘environmental protectionist’ mode, tends to treat the symptoms of environmental mismanagement—pollution—and not the causes—lack of capital, skills, and technology and the absence of the capability to innovate. The challenge will be for governments to ensure that firms operating within their national boundaries remain sufficiently dynamic to be able to afford to clean up when operations cease and to innovate to improve economic efficiency and environmental management in the meantime.

Governments need policy tools that enable them to predict the warning signs of declining competitiveness and impending mine shutdown to ensure sufficient resources are available for the environmental management of mine ‘decommissioning’. Policy mechanisms need to be developed that promote technical change and build up the technological and management capabilities to innovate and manage the acquisition and absorption of clean technology. The privatisation of the state sector and the liberalisation of investment regimes in many developing countries (such as Angola, Mozambique, Namibia, Botswana, Bolivia, Peru, and Chile), with their emerging emphasis on joint ventures and interfirm collaborative arrangements, provide new opportunities for the diffusion of both competitive and environmentally sound best-practice in metals production.

Public policy to promote technical change and, complementing that, to improve economic efficiency respects the interplay between the environmental and economic factors that constitute a sustainable development approach to the long-term environmental management of our nonrenewable natural resources. Environmental regulation at best provides only one element of a public policy for environmental management.

The Nature of the Environmental Problem

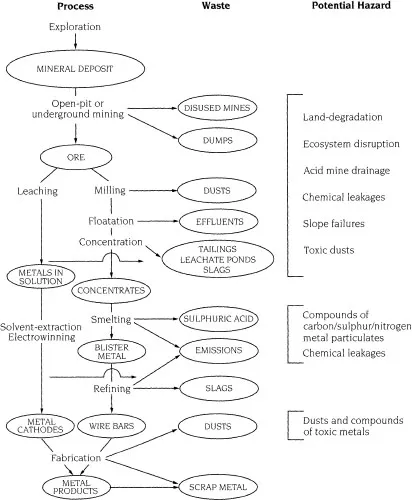

Mining and mineral processing produce waste products and ecological disruption, which may generate potential environmental hazards at each stage of the metal production process. Figure 1 depicts some of these waste products and their associated hazards, which have local, regional, and, to a lesser extent, global manifestations. Mining-related activities affect all three environmental media—land, water, and air. Exploration, mine development, and the dumping of barren overburden or waste can degrade the habitats of local flora and fauna and prohibit alternative land-uses—forestry, agriculture, or leisure. Land effects include land-use conflicts, particularly over sources of energy (such as forests) for mineral processing, and ecosystem disruption. Potentially toxic chemicals—xanthates—are used in primary processing, as are inorganic reagents such as zinc sulphate, copper sulphate, sodium cyanide, and sodium dichromate. The tailings—left by river banks and often in poorly secured ponds—contain residuals of both toxic metals and chemical flotation agents.

Figure 1. The mining process and the environment: processes, waste, and potential hazards are interrelated.

Source: Warhurst 1993

Water quality may be affected by naturally occurring acid mine drainage from mines and waste piles. Certain ores contain considerable quantities of sulphides, which, through oxidation and naturally occurring biological processes, are transformed into sulphates and sulphuric acid, which in turn leach out further metal values from adjacent waste or ore. Water draining from surface mines, wastewaters from processing, and rainwater runoff all require careful monitoring and control, which are rarely undertaken systematically in developing countries, with disastrous results. By their very nature, mine water pollution problems, once they have begun, can only be treated retroactively—if at all—at excessive cost. The oxidation process that creates acid mine drainage is autogenous, and there is no end to the volume of sulphide waste and rock to ‘feed’ it.

Toxic leaks and spillages from tailings dams or reagent ponds may also affect water quality. This applies to the inadequate management of toxic wastes from the hydrometallurgical treatment of gold ores with cyanide and to semiliquid wastes from the concentration and smelting of nonferrous metals, including copper, tin, lead, zinc, silver, and nickel. The red mud slag produced by bauxite mining can also be categorised as potentially hazardous in this respect. Significantly, many of these water quality effects can cause environmental hazards beyond the life of the mine.

Air quality may also be affected by emissions from roasters and smelters, and to a lesser extent from refineries, of compounds of carbon, sulphur, and nitrogen and of toxic metal particulates. There are also indirect emission effects from the use of fossil fuels as energy and potentially hazardous dusts and gases released in the workplace.

It is a complex task to estimate the costs of natural resource degradation associated with mineral exploitation and to design public policy to share those costs among the polluter, state, and community. Increasingly, it is becoming apparent that these costs are high. In the past, the costs have largely been measured in terms of the expense involved in, for example, remedial treatment of degraded water quality, investment in environmental control technologies, or compensation for damage by toxic dust to local farmland. More recently, particularly in North America, environmental costs have been estimated in terms of extensive rehabilitation programmes, which transform the previous mine and plant site for alternative resource uses, such as revegetation or leisure facilities. Indeed, in the context of developing countries, one could argue that the mining industry was traditionally structured to externalise such environmental costs so that the maximisation of profit was achieved not so much through efficiency and innovation, but through the appropriation of undervalued resources and the shifting of the environmental costs of doing so on to others.2

Although some environmental degradation is the inevitable result of mining, examples can be given where pollution either has negative economic impacts or presents economic opportunities—for firms as well as governments. For example, by-products that are toxic but could warrant economic reprocessing are frequently dumped. This is especially the case in developing countries, where inaccurate sampling or inefficient technologies result in such loss. Similarly the mining of high-grade ore and the dumping of low-grade ore, which is a short-term expediency to boost foreign exchange earnings in times of crisis, result in greater environmental degradation (higher risk of acid mine drainage from dumps) and the loss of longer term revenue. Costly water treatment projects are often instigated as part of the mine closure programme rather than implementing acid mine drainage prevention from the outset of the mining project, involving much cheaper pollution control and often resulting in the recovery of metal values. Finally, some firms have been obliged to pay the health care costs of communities as a result of their drinking degraded water, costs which in many cases outweigh the cost of technical change to treat the chemical effluents in the first place.

There is however still considerable work to be undertaken to quantify the nature and extent of environmental degradation caused by metals production. Currently there exist only isolated case studies and little systematic analysis of the problem. It is difficult to generalise since local geology, geography, and climate affect mineral and ore chemistry, soil vulnerability, and drainage patterns, and hence the extent of environmental hazard created. Furthermore, a major factor affecting whether a hazard results in environmental degradation is the social and economic organisation of the production unit, including its size, history, and ownership structure, as well as its propensity to innovate.

Limitations of Environmental Regulation and the Challenge for Public Policy

Regulatory Effectiveness in industrialised Countries

Regulatory frameworks for safeguarding the quality and availability of land, water, and air that might be degraded as a result of mining and mineral processing activities are growing in number and complexity. This has particularly been the case in the major mineral-producing countries of North America and Australia, as well as Japan and Europe. The norm in environmental regulation is that governments set maximum permissible discharge levels or minimum levels of acceptable environmental quality. Such command-and-control mechanisms include: Best Available Technology standards, clean water and air acts, Superfunds for cleanup and liability determination, and a range of site-specific permitting procedures, which tend to be the responsibility of local government within nationally approved regulatory regimes. Command-and-control mechanisms tend to rely on administrative agencies and judicial systems for enforcement. Three issues are relevant regarding the appropriateness of command-and-control environmental regulations for reducing environmental degradation and improving environmental management practices in metals production.

First, there is a trend away from a ‘pollutee-suffers’ to a ‘polluter-pays’ principle. However, it remains the case that the polluter pays only if discovered and prosecuted, which requires technical skills and a sophisticated judicial system, and that this occurs only after the pollution problem has become apparent and caused potentially irreversible damage. This highlights the tendency of such environmental regulations to deal with the symptoms of environmental mismanagement (pollution) rather than its causes (economic constraints, technical constraints, lack of access to technology or information about better environmental management practices). This can be serious in some instances, because once certain types of pollution, such as acid mine drainage, have been identified, it is extremely costly and sometimes technically impossible to trace the cause, rectify the problem, and prevent its recurrence. Certain environmental controls may only work if incorporated into a project from the outset (e.g., buffer zones to protect against leaks under multitonnage leach pads and tailings ponds).

Second, Best Available Technology (BAT) standards may be appropriate at plant start-up, but their specified effluent and emission levels are not necessarily achievable throughout the life of the plant, because technical problems may arise and there may be variations in the quality of concentrate or smelter feed, etc., if supply sources are changed. Moreover, there are serious implications for monitoring. It would also be erroneous for a regulatory authority to assume standards are being met if a preselected item of technology has been installed. Ongoing management and the environmental practices at the plant are also likely to be important determinants of best environmental practices.

Third, related to points one and two above, BAT standards and environmental regulations of the command-and-control type tend to presume a static technology—a best technology at any one time. This tends to promote incremental, add-on controls to respond to evolving regulation rather than to stimulate innovation. This acts as a disincentive to innovate by equipment suppliers, mining firms, and metal producers. Their innovation, which has required substantial R&D resources, may be superseded by some regulatory authority's decision about what constitutes BAT for their particular activity. BAT gives the impression of technology being imposed from outside the firm, not generated from within. The search for profit and cost-savings tends to be a more obvious instigating factor of technical change, and it might be argued that market-based mechanisms, a technology policy that is complemented by a regulatory framework, and a good corporate environmental management strategy can better contribute to achieving that aim.

There has been growing interest in the use of market-based mechanisms, whereby the polluter is charged for destructive use by estimating the damage caused. An important justification for the use of market-based incentives is that they allow firms greater freedom to choose how best to attain a given environmental standard (OECD 1991). By remedying market failures or creating new markets (rather than by substituting government regulations for imperfectly functioning markets), it has been argued, market-based incentives may permit more economically efficient solutions to environmental problems. Two categories of incentives exist (O'Connor 1991; Warhurst and MacDonnell 1992). One set, based on prices, includes a variety of pollution taxes, emission charges, product charges, and deposit-refund systems. Another set is quantity-based and includes tradeable pollution rights or marketable pollution permits. The most common of these measures relates to posting bonds up front for the rehabilitation of mines following closure. This is standard practice now in Canada and Malaysia. There are also discussions taking place about a mercury tax in Brazil and a cyanide tax in the United States. Currently, no government has designed a systematic set of incentives for industry to innovate and develop new environmental technology.

There are two further areas where policy approaches can contribute to improved environmental management practices. The first approach increases the use of conditionality in the provision of private, bilateral, and multilateral credit. This approach frequently requires both prior environmental impact assessment and the use of best-practice environmental control technologies in new mineral projects. A growing number of donor agencies in Germany, Canada, Finland, and Japan, for example, are also concerned with training in environmental management. The second approach encompasses the attempts by some governments, particularly Canada, to stimulate R&D activities (jointly and within industry and academic institutions) to determine toxicity from mining pollution and to promote cleanup solutions. For example, Canada has extensive government-funded R&D programmes to promote the abatement of acid mine drainage and of sulphur dioxide emissions. There is considerable scope for expanding these approaches, as will be argued below.

Regulatory Effectiveness in Developing Countries

Environmental regulations designed specifically for mining and mineral processing have until recently been uncommon in developing countries, although most countries now have in place basic standards for water quality and, less commonly, air quality. A few developing countries have recently adopted extensive regulatory frameworks—sometimes replicas of U.S. models. This, for example, has been the case in Chile and, to a lesser extent, in Brazil. This growing concern about environmental degradation is occurring during a period of rapid liber...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contributors

- Table of Contents

- Preface

- Mining and the Environment: An introduction and Overview

- Land Access for Mineral Development in Australia

- Mining Waste and the Polluter-Pays Principle in the United States

- Developing National Policies in Chile

- Experimenting with Supranational Policies in Europe ill

- The Limitations of Environmental Regulation in Mining