- 255 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Satire, according to Jonathan Swift, is a mirror where beholders generally discover everybody's face but their own. and over twenty-four centuries the mirror of satirical literature has taken on many shapes. Yet certain techniques recur continually, certain themes are timeless, and some targets are perennial. Politics (the mismanagement of men by other men) has always been a target of satire, as has the war between sexes.The universality of satire as a mode and creative impulse is demonstrated by the cross-cultural development of lampoon and travesty. Its deep roots and variety are shown by the persistence of allegory, fable, aphorism, and other literary subgenres. Hodgart analyzes satire at some of its most exuberant moments in Western literature, from Aristophanes to Brecht. His analysis is supplemented by a selection and discussion of prints and cartoons.Satire continues to help us make sense of the conventions that seem to have been almost genetically transmitted from their satiric ancestors to our digital contemporaries. This is especially evident in Hodgart's repeated references to satire's predilection for the ephemeral, for camouflaging itself among the everyday, for speaking to the moment, and thus for integrating itself as deeply as possible into society. Brian Connery's new introduction places Hodgart's analysis in its proper place in the development of twentieth-century criticism.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Satire by Matthew Hodgart in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Linguistics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Origins and principles

The perennial topic of satire is the human condition itself. Man, part ape and part essence, is born for trouble as the sparks fly upwards. He is notoriously a weak and mortal creature, and during his brief span of life suffers the heart-ache and the thousand natural shocks that flesh is heir to. His desires, physical and mental, are boundless, and by the nature of things most of them are doomed to remain unfulfilled, those which are fulfilled often having unexpectedly unpleasant consequences. Man is ceaselessly engaged in solving the problems set by nature - but every problem that he solves creates new ones: thus, the conquest of disease leads to over-population and the unhappy survival of the old; the demands of our increasingly complex civilisation lead to more and more tension and frustration. There would not seem to be any conceivable future less problematical than the troubled past, less full of absurdities than the nightmare of history. There are many ways of looking at this life, and satire's is one of them. To respond to the world with a mixture of laughter and indignation is not perhaps the noblest way, nor the most likely to lead to good works or great art; but it is the way of satire. Satire, 'the use of ridicule, sarcasm, irony etc. to expose, attack, or deride vices, follies etc.' (as the dictionaries define it), has its origin in a state of mind which is critical and aggressive, usually one of irritation at the latest examples of human absurdity, inefficiency or wickedness. If the occasions for satire are infinite and inherent in the human condition, the impulses behind satire are basic to human nature. Indeed, they probably go back beyond human nature, to the psychology of our animal forebears. All social animals are aggressive to their own kind: each of their societies possess a hierarchy, sometimes known as a 'pecking order', by which its efficient functioning is maintained. To establish this order, two animals will use 'threat displays' against each other, until the inferior submits to the superior. The human expression of contempt, the curling lip and the mocking laugh, seem to be rooted in such threat displays; and the satiric impulse is probably more closely connected with this kind of aggressive behaviour than with overt attack, such as animals make against other species. The satirist's anger is modified by his sense of superiority and contempt for his victim; his aim is to make the victim lose 'face', and the most effective way of humiliating him is by contemptuous laughter. As is well known, horses and dogs do not like to be laughed at.

That is as far as we need go for the moment into the motivation of satire. It does not, of course, answer two questions: how does satire become art? and how does satire differ from other kinds of literature? It is, after all, only with art and in particular with the art of literature that we are to be concerned. First and most obviously, satire can turn from a state of mind into art only when it combines aggressive denunciation with some aesthetic features which can cause pure pleasure in the spectator. The spectator, indeed, may identify himself with the satirist and share his sense of superiority; but that is not enough. There must be other sources of pleasure in the satire, as for example patterns of sound and meaning, or the kind of relationship of ideas that we call wit, which we can feel as beautiful or exciting in themselves, irrespective of the subject of the satire. But many kinds of denunciation or sermon, however wittily or elegantly phrased, are not generally accepted as satire unless something else is involved. There is an enormous amount of polemical criticism, invective, political journalism and so on which is intensely critical of social and moral conditions, and may be very well expressed, yet fails to enter that realm ruled over by Juvenal and Swift and inhabited by even the minor masters of the art. I would suggest that true satire demands a high degree both of commitment to and involvement with the painful problems of the world, and simultaneously a high degree of abstraction from the world. The criticism of the world is abstracted from its ordinary setting, the setting of, say, political oratory and journalism, and transformed into a high form of 'play', which gives us both the recognition of our responsibilities and the irresponsible joy of make-believe. So with more personal satire: the tension and bitterness evoked by unpleasant personal relationships are transmuted into delight at the creation of a beautifully absurd figure which is both like and unlike the subject. One recognises true satire by this quality of 'abstraction'; wit and other technical devices (discussed in a later chapter) are the means by which the painful issues of real life are transmuted. But even more important is the element of fantasy which seems to be present in all true satire. The satirist does not paint an objective picture of the evils he describes, since pure realism would be too oppressive. Instead he usually offers us a travesty of the situation, which at once directs our attention to actuality and permits an escape from it. All good satire contains an element of aggressive attack and a fantastic vision of the world transformed: it is written for entertainment, but contains sharp and telling comments on the problems of the world in which we live, offering 'imaginary gardens with real toads in them'. It would seem, then, that satire is distinguishable from other kinds of literature by its approach to its subject, by a special attitude to human experience which is reflected in its artistic conventions. It is in fact very difficult to distinguish it clearly from other literary forms on any other basis; first, because it does not clearly form one of the traditional 'genres', and secondly because it may assume a bewildering variety of sub-forms. The traditional genres, such as epic, tragedy and comedy, were long considered to be self-contained and clearly defined. Each grew out of a particular stage of social development: epic out of the 'heroic' society of warrior aristocracy, tragedy out of the religious and moral preoccupations of the Greek city-states. Each was at a later stage established by convention, and codified by literary critics, and imitated by generations of writers so that norms of epic and tragedy were set up and lasted for centuries. No such stabilising process ever affected satire, with the partial exception of Roman formal satire (the loose monologue in verse on a variety of moral topics). This was much imitated, as we shall see, by classicising poets of the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, but even in these convention-bound centuries, writers who wanted to make satirical comments on the world's absurdities felt free to use a variety of other forms. The satirists have in fact from the beginning used a bewildering range of vehicles, some of which I shall describe in a later chapter. Apart from (1) formal satire, the following categories can be mentioned: (2) the fantastic narrative, which includes such forms as the beast-fable, Utopian or anti-utopian fiction, and allegory; (3) already existing literary forms taken over and transformed into satirical comment, e.g. the aphorism and epitaph; (4) parts of literary works in any of the genres taken over for satirical purposes. Some of the best satire in literature occurs episodically or fragmentarily in works which are not intended to be wholly satirical, It would be absurd to leave out Dickens from this survey, yet his best satirical passages often occur sandwiched between sentimental and melodramatic passages, and in novels whose overall vision of the world is other than a satirical one. The usual genres in which satire appears episodically are comedy and the novel; but it may appear almost anywhere else, even in sermons and not least in Shakespearian tragedy. Faced with even these varieties of form (and there are many more) critics have, not surprisingly, been unable to reach agreement on the strict definition of satire. The definition of tragedy by 'rules' of structure and style may be artificial, but it has seemed since Aristotle to be at least a possibility and it is still being attempted. Critics have never felt happy about applying these kind of criteria to the Protean body of satirical literature. Yet what is commonly called satire is a distinct part of our literary experience: any two experienced readers will show a fair measure of agreement in applying the word to something they have read. In trying to define the term and to explain the special literary experience that satire gives, it may be best to abandon the traditional methods of literary classification and instead to consider the satirist's attitude to life and the special strategies by which he communicates this attitude in literary form. One way of approaching this question is by looking at the oldest and simplest examples of satire available. The emergence of satire, if not as a formal genre, then at least as a distinct type of literature, is probably very ancient. It can apparently be found in the literature of the primitive peoples whose words have been recorded and who may be thought to have preserved the most ancient traditions of mankind. It is striking that two of these literary traditions appear in the special combination of realism and fantasy which, as I have suggested, is the keynote of true satire. One is the 'lampoon' or personal attack; the other is the 'travesty', or fantastic vision of the world transformed.

In the literature of primitive peoples both types can be seen clearly, sometimes separately and sometimes in combination. 'Literature' is not a very satisfactory word, since it implies letters, while the most primitive peoples are illiterate; but no one has found a better word for the art of verbal expression, so I shall use it without further apology. Nor shall I apologise for discussing primitive literature, since it is not essentially different from the more sophisticated literature of higher civilisations. The problems of living, the experiences of love and death, the delights and miseries of primitive men are not so very different from ours; and many men from a simpler world even than Homer's have found out how to express such things movingly in words. The anthropologist Paul Radin has pointed out that every primitive society has a highly developed literary culture, in which nearly all the genres of sophisticated literature appear more or less distinctly, sometimes presented with astonishing poetic or narrative skill, with satire conspicuous among them:

I know of no tribe where satires or formal narratives avowedly humorous have not attained a rich development. Examples of every conceivable form are found, from broad lampoon and crude invective to subtle innuendo and satire based on man's stupidity, his gluttony, and his lack of a sense of proportion1.

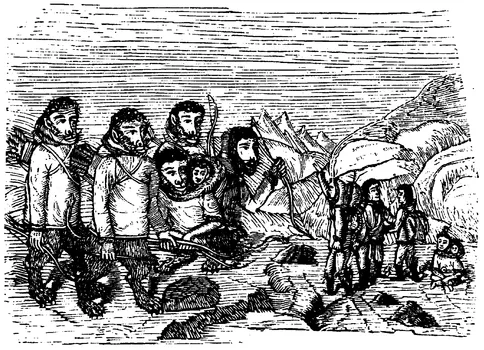

The simplest example of the first type (lampoon, invective) is the Eskimo song of derision. Eskimo society was until recently on about the same level as that of the late Stone Age: it lacked any distinct system of law, let alone police or magistrates to enforce the law, or schoolmasters or preachers to warn against misconduct: its religion has no strong supernatural sanctions such as a hell where evil-doers will be punished. The chief means of punishing bad social behaviour is by the satirical song, which makes the delinquent hang his head in shame. The Eskimo satirist has precisely the same aim as Alexander Pope, to make 'men not afraid of God afraid of me'. This is said to work in practice: the man who is worsted in a satirical song-contest will try to reform himself; in extreme cases one can picture him stumbling wretchedly out of the igloo, like Captain Oates on Scott's polar expedition, to rid the community of its obnoxious burden - which is more than Pope's victims ever did. I have not found any translations of great merit but as an illustration 'The Strife of Savadlak and Pulangitsissok' will serve:

Eskimo engraving of the nineteenth century, one of a series illustrating traditional tales. It shows creatures, half-human and half-dog, who, like the perfect satirist, can kill merely by pointing their bows. From Riuk, Tales and Traditions of the Eskimo, a Danish work.

There was a time when Savadlak wished that I would be a good

kayaker.

That I could take a good load on my kayak!

Many years ago one day he wanted to put a heavy load on my kayak,

When Savadlak had his kayak tied to mine (for fear of being capsized).

Then he could carry plenty upon his kayak,

But I had to tow him and he cried most pitifully.

And then he grew afraid,

And nearly got upset,

And he had to keep his hold by means of my kayak string2.

kayaker.

That I could take a good load on my kayak!

Many years ago one day he wanted to put a heavy load on my kayak,

When Savadlak had his kayak tied to mine (for fear of being capsized).

Then he could carry plenty upon his kayak,

But I had to tow him and he cried most pitifully.

And then he grew afraid,

And nearly got upset,

And he had to keep his hold by means of my kayak string2.

Other songs insist that the victim's sexual desires are unlimited, his performance totally inadequate - much as Rochester and other Restoration wits used to write in their lampoons on Charles II, no less crudely. Satire-duels of this kind are also found among the Indians of the north-west coast of America and in Melanesia. They cannot all be described as moral in intention, since some consist of direct attacks on individuals for the purpose of revenge or the assertion of superiority; but insofar as literature is a public activity and thus preferable to private violence, they contain the germ of moral and also of political satire; that is, of literature as propaganda for right action, which 'heals with morals what it hurts with wit'.

This primitive kind of satire or lampoon keeps appearing throughout literature. When Dr Johnson was asked why Pope put a certain line in his Dunciad, he replied, no doubt correctly, 'Sir, he hoped it would vex somebody'. At the simplest there is Martial's epigram in its well-known adaptation:

I do not love thee, Doctor Fell,

The reason why I cannot tell;

But this I know and know full well:

I do not love thee, Doctor Fell.

The reason why I cannot tell;

But this I know and know full well:

I do not love thee, Doctor Fell.

At the most complex and elegant there are A.E.Housman's strictures on the incompetent scholars who had dared to edit the text of Manilius (one of whom had the misfortune to come from Strasbourg, 'a city famous for its geese').

The primitive lampoon is closely related to the curse, and the curse or imprecation is based on beliefs in the magical power of the word. By an effective combination of images and rhythms, and by the invocation of supernatural forces the curse is intended to exert a positive influence over its victim, to make him shrivel up or die, or a negative influence, to restrain his powers of doing evil. That, at least, is one way of putting it, as has been done brilliantly by R.C.Elliott in his book The Power of Satire, who traces satire back to magic spells and rituals. Just as one type of primitive ritual is designed to increase the fertility of the crops or to cast love-spells, so another is designed to cast out demons or to cause the tribe's enemies to perish in battle; both have been exhaustively discussed by Frazer in The Golden Bough. In this view, satire springs from primitive witchcraft; it is thus the verbal equivalent of pointing the death-bone and causing an Australian aborigine to die of sheer terror, or, perhaps better, of making a wax image of your victim and sticking pins in it. But this only raises the question: why is the word considered to be magical? The answer may be simply that the word is magical because of its satirical, that is, its literary power. A curse, like all other literary forms is effective just as far as it is well composed, in compelling rhythms, skilful rhetoric, relevant argument and true content - which are among the normal criteria for all good literature. Wizards, of course, may sometimes mumble a curse in a dead language or in nonsense words, but even then the literary qualities of sound and rhythm would seem to be important. Most primitive curses or lampoons, however, seem to be lucid and meant for effective communication, like this love-curse from the Ba-Ronga of south-eastern Africa:

Refuse me as much as you wish, my dear!

The corn you eat at home, it is made of human eyes!

The goblets that you use, they are of human skulls!

The manioc roots you eat, they are of human shin-bones!

The potatoes you eat, they are of human hands!

Refuse me as much as you wish!

No one desires you!3

The corn you eat at home, it is made of human eyes!

The goblets that you use, they are of human skulls!

The manioc roots you eat, they are of human shin-bones!

The potatoes you eat, they are of human hands!

Refuse me as much as you wish!

No one desires you!3

That could hardly make its point more tellingly. Savages, as anthropologists tell us, are practical people, and they have very good practical reasons for believing in the power of the word. They have discovered empirically, by trial and error, just how much the word can do if it is properly employed, as the example of the Eskimos shows. The word used with literary art really can affect people in a striking way, even to the point of sickness and death. Poor Keats was not the only one to be 'snuffed out by an article'; every sensitive author knows the unpleasant psychosomatic effect of a clever and hostile review (and some reviewers know it too). Most people cannot bear to hear themselves abused in a true and witty manner, which excites the scorn of the audience. I am told that among certain primitive peoples, the tongues of condemned criminals were torn out before their execution, lest in their last minutes alive they should say something damaging to their j...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Introduction to the Transaction Edition

- Introduction

- 1 Origins and principles

- 2 The topics of satire: politics

- 3 The topics of satire: women

- 4 Techniques of satire

- 5 Forms of satire

- 6 Satire in drama

- 7 Satire in the novel

- Postscript

- Notes

- Acknowledgments

- Index