![]()

1 ELEPHANTS IN DECLINE

Introduction

Are elephants worth more dead than alive? This is not a trivial question. It is in fact the key economic problem that any inquiry into elephants and the ivory trade has to address. We know that the ivory harvested from elephants has a high commercial value, which is increasing as the population becomes scarce. But is this increasing scarcity and commercial value a crucial determinant of the elephants’ decline in Africa, or might it also be part of the solution to conserving elephant populations? Elephants also have other values than their ivory. Elephants are one of Africa’s “big five” species of large mammals that are major tourist attractions. Elephants also have an important ecological role in opening up areas for livestock and in ensuring ecological balance. On the other hand, elephants are also known to cause extensive crop and other economic damage where there are land-use conflicts between the species and human populations. Do these additional non-ivory values of elephants provide sufficient incentives for preserving the African elephant, and can we manage elephant populations so as to maximize their total economic value, including ivory values where appropriate? How does regulation of the ivory trade contribute to this sustainable management of elephant populations, and can we design an effective international regulatory mechanism towards this end?

This book attempts to address these questions. We recognize that there are no easy solutions. Indeed, we are only just beginning to ask the right questions and to consider that elephants and the ivory trade are an economic problem. We are unaware of any other book that examines the ivory trade, its regulation and its implications for elephant management from a truly economic perspective. Hopefully, we can make some contribution to the ongoing international debate over the future of the African elephant and the appropriate steps needed for its sustainable management.

The Decline of the African Elephant

The population of elephants in Africa has halved in eight years from 1.2 million to just over 600,000.1 Kenya’s elephant population alone has declined by two-thirds from its 1981 population of 65,000 to 16,000 in 1989. During the same period Tanzania has lost over 130,000 elephants and Zambia 128,000 – almost three-quarters of its 1981 population. Although the data presented in Table 1.1 indicate that populations have been rising in the central, forested regions of Africa, such as Gabon and Congo, this is due to improved population counts rather than rising population levels. In only a few African countries – South Africa, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Malawi and Namibia – are numbers at least stable. Population projections by the Renewable Resources Assessment Group (RRAG) at Imperial College, London in a report to the Ivory Trade Review Group (ITRG) suggest that, at the rate of decline seen in 1986, elephants could be extinct by 2010.2

Table 1.1: Elephant numbers: regions and selected countries

| 1981a | 1989b |

Zaire | 376,000 | 112,000 |

| CAR* | 31,000 | 23,000 |

Chad | NA | 2,100 |

Congo | 10,800 | 42,000 |

Equatorial Guinea | NA | 500 |

Gabon | 13,400 | 74,000 |

Central Africa Total | 436,200 | 277,000 |

Kenya | 65,000 | 16,000 |

Tanzania | 203,900 | 61,000 |

Sudan | 133,000 | 22,000 |

Ethiopia | NA | 8,000 |

Rwanda | 150 | 50 |

Somalia | 24,300 | 2,000 |

Uganda | 2,300 | 1,600 |

East Africa Total | 429,500 | 110,000 |

Botswana | 20,000 | 68,000 |

South Africa | 8,000 | 7,800 |

Zambia | 160,000 | 32,000 |

Zimbabwe | 47,000 | 52,000 |

Angola | 12,400 | 18,000 |

Malawi | 4,500 | 2,800 |

Mozambique | 54,800 | 17,000 |

Nambia | 2,300 | 32,000 |

Southern Africa Total | 309,000 | 204,000 |

Benin | 1,250 | 2,100 |

Burkina Fasa | NA | 4,500 |

Ghana | 970 | 2,800 |

Guinea | 800 | 560 |

Guinea Bissau | NA | 40 |

Ivory Coast | 4,800 | 3,600 |

Liberia | 2,000 | 1,300 |

Mali | 780 | 840 |

Mauritania | 40 | 100 |

Niger | 800 | 440 |

Nigeria | 1,820 | 1,300 |

Senegal | 200 | 140 |

Sierra Leone | 500 | 380 |

Togo | 150 | 380 |

West Africa Total | 17,600 | 15,700 |

Africa Total | 1,192,300 | 622,700 |

Note: * = Central African Republic

NA = not available

a UNEP/IUCN/WWF, Elephants and Rhinos in Africa – A Time for Decision, (1982). Based on findings and recommendations of the African Elephant and Rhino Specialist Group.

b Recent estimates (October 1989) from Ian Douglas-Hamilton of the African Elephant and Rhino Specialist Group.

There are two species of African elephant, the bush or savannah elephant, Loxodanta africana africana, and the forest elephant, L.a. cyclotis. In the past, the impact on the forest elephant of harvesting ivory was not thought to be as significant as for the savannah elephant. Instead, human population pressure for land was considered a major population constraint. However, more recent evidence suggests that the rate of decline of the forest elephant may be similar to that of the savannah elephant, although this population reduction is more conspicious in the savannah region.3 Thus we have now reached the stage where for all African elephants the poorly managed international trade in ivory, and the illegal hunting serving this trade, are the most significant factors in the decline of the elephant population.

There is evidence that the way in which elephants are harvested is further precipitating their population decline. The main cash value of the elephant is its tusks, although the hide is also demanded both internationally and locally, and the meat is often consumed locally. Poaching has seriously disrupted breeding patterns in some herds because gunmen pick off elephants with big tusks, typically the older and more sexually active males. In Tanzania’s Mikumi reserve, where poachers are very active, the ratio was 99.6 per cent females to 0.4 per cent males. Populations in Queen Elizabeth Park in Uganda and Tsavo in Kenya are similarity skewed. An elephant cow is fertile for only two days during her three-monthly oestrus, and must find a rutting male during this brief period. The chances of mating successfully under these conditions are slim. What is more, with the male populations decimated, poachers turn their attentions to the smaller tusked females. Studies in Amboseli National Park, Kenya show that for every adult female elephant killed at least one immature elephant will die. A calf younger than two years old stands no chance of surviving the death of its mother, while a calf orphaned between two and five years old has a 30 per cent chance of survival, and one aged between six and ten years old has a 48 per cent chance of survival.4

This dramatic decline in elephant numbers in most of Africa has been largely attributed to illegal harvesting, i.e. poaching of elephants for ivory. In recent years, poaching and the decline of the African elephant have become synonymous in the public mind. However, the situation is more complicated than that.

The Role of the Ivory Trade

Set against this population decline, the historical trend in the international ivory trade has been one of sustained growth from 1945 through the mid-1980s – from 204 tonnes of raw (i.e. unworked) elephant ivory in 1950 to 412 tonnes in 1960, 564 tonnes in 1970 and around 1,000 tonnes in 1980. This represents a greater than 400 per cent increase in the trade in ivory over 40 years, or over 10 per cent per annum each year for the four past decades. Best estimates of the trade occurring in the last decade are given in Table 1.2. Up to 1986, records indicate that between 700 and 1,000 tonnes of raw ivory were traded internationally each year.

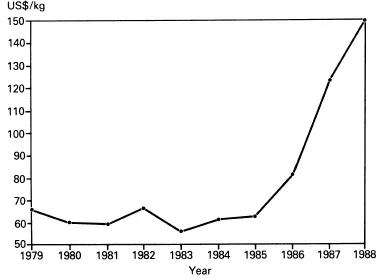

As shown in Figure 1.1, the price of ivory has been increasing dramatically: between 1979 and 1985 the current price of one kilogram of ivory was around $60, in 1987 it reached over $120 and in early 1989 it rose towards $300 per kilogram. Thus the ivory trade is a highly lucrative activity. (All prices are given in US dollars unless otherwise stated.)

Table 1.2 shows that the sum total of ivory exported between 1979 and 1988 amounts to between 7,624,882 and 7,954,544 kg (see also Chapter 2). As a very approximate guide it can be taken that an average pair of tusks weighs 9–10 kg (although this is a dangerous assumption as average tusk weights have changed over time) and from this it can be estimated that during this period between 700,000 an...