- 244 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Community Transport: Policy, Planning and Practice

About this book

This book explores the strategic significance of community transport, identifies and analyses the key issues which face community transport, and presents an analytical and evaluative account of the role, status and future of community transport.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Community Transport: Policy, Planning and Practice by D. Gillingwater,J. Sutton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business generale. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

THE HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF COMMUNITY TRANSPORT

INTRODUCTION

The development of ‘community transport’ and the reasons for its rapid growth in the past two decades are explored in this introductory chapter. The history and evolution of community transport – often referred to as the ‘CT sector’ – is traced and the organisation of a variety of services is described, primarily from a United Kingdom (UK) perspective. From an analysis of their operations and the changing environment within which they operate, we try to evaluate their contribution within the domain of public passenger transport services and examine the scope for their future development.

The objectives of this chapter are twofold: first, to provide an overview of recent trends in the provision of these specialised services; and, second, to provide a context for the deliberation of those issues which are covered in more detail in the remaining chapters.

Community transport services make use of accessible vehicles to meet local transport needs not catered for by conventional public transport. They are provided in the main by not-for-profit, voluntary-managed and community-based organisations rather than commercial companies or public sector transport agencies. They are often referred to as ‘specialised’ transport services. This differs from the organisation of services to be found in, for example, North America and Europe, where ‘paratransit’ as well as ‘specialised’ services are to be found. (The European dimension is explored in greater detail in Chapter 2.) However, the situation in the UK has been and is changing, as later discussion will show. The comparative independence of community transport is revealed in the examples which follow, all of which cater for the transport needs of people who are experiencing some form of mobility handicap.1

While public sector agencies may account for the majority of specialised transport services for such people, the growth in voluntary-organised community transport has, in many respects, been the more remarkable. The first recognised community transport scheme in the UK, for example, only began operation in Birmingham in 1966; in the years since there has been a phenomenal growth in the number of these types of transport projects. The reasons behind this explosion in transport provision, to number more than 300 community transport projects in 1984 and perhaps around a thousand in 1990, are explored below.2

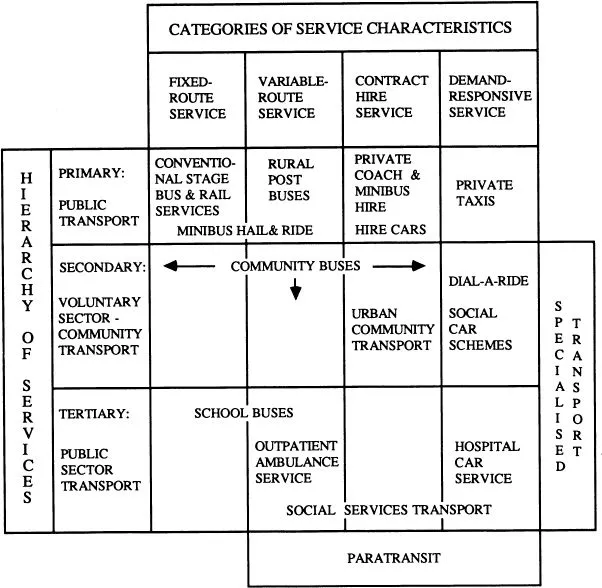

The term ‘community transport’ is used here to refer to those ‘secondary’ modes of transport shown in Figure 1.1, and include the following services:

• social car schemes

• group hire minibus projects, and

• dial-a-ride services

Figure 1.1 provides a taxonomy of services and illustrates the terminology in current use to describe them. The distinctions drawn between the variety of services and the existence of some form of hierarchy in public transport are not adequately represented by the taxonomy, but the fact that such distinctions are made by professionals and institutions on the basis of service characteristics like these (some of which are enshrined in legislation) shapes perceptions towards these services and furthermore influences policies in, for example, the distribution and use of transport resources. This particular issue is covered in more detail in Chapter 3, so the discussion here will accept the basic premise that some form of hierarchy exists into which community transport has interspersed itself. The significance of public sector specialised transport services have been described by the authors and others elsewhere.3

Source: Sutton (1988)3

Figure 1.1: A Taxonomy of Passenger Transport Services in the UK

Although ‘community transport’ is usually associated with voluntary effort, it is important to distinguish here between the ‘voluntary sector’ and ‘voluntary work’. The latter consists of individuals who undertake unpaid work for charitable, that is non-profit making, purposes. The former, however, is less easy to define: sometimes it is referred to as the ‘informal economy’, where individuals undertake not only paid work but also to further a particular social end. The only common denominator is their independence from government or private control and their commitment to the improvement of social conditions – in this case the overcoming of mobility handicap. Within community transport there are, for example, projects which employ full-time paid staff to organise and provide services, and where the voluntary input is managerial and located in a management committee. These distinctions are discussed because, as community transport has grown and developed over the years, their operating practices have come to resemble the public sector services in the type and range of services provided to client groups, but without gaining recognition of their status as transport providers. As Chapter 4 shows, the boundaries separating community transport from the public sector have become blurred over the last decade, at least in operational terms, but the institutional separation of the two sectors continues. These institutional barriers are a major factor which has helped to shape the organisation and provision of community transport services in the UK. (The issues arising here are examined and developed further in Chapters 5 and 6.)

In the last two decades the voluntary sector has become more influential in the UK; it is now regarded as an important pillar of the social welfare state, irrespective of any particular government’s ideological commitment.4 This is particularly true of the period since the reorganisations of local government and the National Health Service in 1974. In both cases, measures incorporating the ideals and philosophy of voluntarism were designed into their respective corporate structures – an example being the increasing control of the voluntary hospital car service by the ambulance service. The support of the voluntary sector has now become essential for the effective delivery of many social welfare services, and this includes community transport. As Norman has commented5:

“Voluntary schemes can be used to provide local public transport where commercial operation is uneconomic; to provide specialist transport to health centres and other medical or social services; to carry elderly people to day clubs and day centres; to take elderly visitors to distant hospitals and to meet a host of individual needs. Without it many statutory services could not run at all and many elderly people’s lives would hardly be worth living.”

When discussing organisations within the voluntary sector, it is important to recognise the context within which they operate and in particular how their roles are shaped by their inter-relationships with statutory agencies. Community transport is a growth area within the voluntary sector which has been acknowledged by the National Council for Voluntary Organisations since 19816, but community transport projects have found it difficult to gain acceptance in their own right either as a local authority-orientated social services transport activity or as an accessible public transport service. Falling between the administrative ‘stools’ of local authority social services departments, planning and transportation departments, and health authorities/trusts (and fitting uncomfortably under any of their wings) has meant that recognition of the role of community transport and support from public sector agencies for their services has been patchy. However, since the Transport Act of 1985 (and for London, the 1984 London Regional Transport Act), a duty has been placed on transport authorities to provide for those with a mobility handicap (in this case defined as public transport for elderly and disabled persons), together with greater involvement and the deployment of additional resources, especially in metropolitan areas.

A TYPOLOGY OF COMMUNITY TRANSPORT

Social Car Schemes (SCS)

Voluntary organised social car schemes (SCS) have been in existence since at least 1939 and are a popular form of community transport provision, especially in rural areas. In recent years, successive governments have sought to encourage the provision of social car schemes, for example, through legislation in the 1980 Transport Act. This removed restrictions to their operations and allowed them to advertise their services. Voluntary car services were pioneered by the Women’s Royal Voluntary Service (WRVS) and Women’s Institutes (WI), and they remain major providers of services. The nature of social car schemes, however, has changed over the years: on the one hand, the volunteer effort has often been institutionalised and incorporated into the public sector, as is the case with the hospital car service and with the social car schemes organised by local authority social services departments; while on the other, the services have moved away from meeting ‘urgent’ needs, such as hospital trips, to include other types of journey, such as shopping. These latter trips are often encouraged by local authorities who, in some cases, regard the social car scheme as a supplementary form of public transport – for example, Clwyd has supported social car schemes through its public transport budget7, as have many other county councils.

There are four main types of social car scheme:

• Non-organised ‘informal’ lift giving – for example, between neighbours;

• Locally-organised car pools meeting general needs, such as a village car scheme with volunteer drivers using their own vehicles;

• Local agencies which recruit drivers to meet social needs over a larger area, such as a district-wide volunteer bureau or through a Council for Voluntary Service; and

• Centrally-organised schemes in collaboration with a public agency (e.g. a hospital), such as a hospital car scheme or a WRVS scheme providing a service for the local authority social services department.

Social car schemes are important providers of specialised transport services; for example, the hospital car service alone is estimated to have carried over three million passengers in 1978, rising to 3.4 million by 1986, or 18 percent of all outpatient journeys.8 The extent of informal lift giving is difficult to estimate but two studies undertaken by the Department of Environment in 1971 (in Devon and West Suffolk) suggested that they accounted for more journeys than was generally realised.6,9 However, evidence collected as part of the Rural Transport Experiments (RUTEX) programme (1976–79) did not support this view and it is questionable whether informal lift giving can be regarded as constituting a transport service per se which can be relied upon to meet local needs.10

Other locally organised services – car pools and local agency provision – were investigated in a survey by the National Council of Social Services in 1978, which recorded 98 schemes in operation in England and Wales.11 The average number of passengers carried annually in each scheme was 266, which compared with an annual average in WRVS organised schemes of 1,082 passenger journeys. The comparable figures for non-WRVS schemes are considerably lower and reflect their status as small local providers.

Most SCS transport is for health-related activities, followed by local authority social services-related activities. This is unsurprising since they are generally dependent for funding on the reimbursement of mileage expenses from the social services and health authorities/trusts. Only a small proportion of journeys are for personal business. In Nottinghamshire the County Council, in collaboration with the Rural Community Council, has been attempting to organise village car services which meet a wider range of needs, especially where conventional public transport services are absent or infrequent, by providing grants from its rural transport experiments budget and as part of its public transport planning function. By 1987, 17 village car services had been established and these were making an average of 855 journeys per month per scheme. In some areas, local coordinators have been employed to develop networks of social car services – Shropshire being a good example – with some success. These Rural Transport Advisers, as they are often known, also support other transport initiatives.

The major problem facing SCS organisers is being able to plan services and recruit drivers against a background of inconsistency in funding by public sector agencies. For example, in Nottinghamshire the hospital car service has been incorporated into the ambulance service and included as part of the latter’s budget, but volunteer bureaux which are attempting to meet a wider range of needs are often refused assistance because their services are not specific or tied to institutional activities like hospitals. Most of these schemes are organised by volunteers, not paid staff, and administration expenses (e.g. telephone calls) have to be met out of the general funds of the sponsoring Bureau (which explains in part why hospital car services carry more passengers and are better organised). The role of SCS could be enhanced if funding were available to cover running costs; in urban areas, where a full-time organiser may be required, they can provide a large number of journeys, as two case studies in Plymouth and Birmingham have demonstrated.12

The problem for funding agencies, like local authorities, is deciding upon the status of the social car scheme. The key questions are: should they continue to be funded separately by local authority social services and health authorities/trusts for institutional trips, or could they be funded to provide public transport journeys where the latter are either scarce or non-existent? The voluntary sector itself is divided on this issue because, like most other specialised transport services, the ramifications of accepting a wider role are not clearly understood: for example, whether this would reinforce trends to reduce further the already limited provision of rural bus services. In the final analysis their public transport role is likely to be limited, and in general the evidence so far suggests that they are best organised to support institutional activities, except in more remote rural areas where, given local commitment and resources, other journeys can be catered for. This role is itself continuing to grow but it is in relation to health and social service activities that social car schemes are considered most important...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- List of Tables

- List of Figures

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 THE HISTORY AND EVOLUTION OF COMMUNITY TRANSPORT

- 2 DEVELOPING ACCESSIBLE TRANSPORT: THE EUROPEAN EXPERIENCE

- 3 TRAVEL CHOICE AND THE MOBILITY HANDICAPPED

- 4 RESOURCING ACCESSIBLE AND NON-CONVENTIONAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT

- 5 EQUITY AND EFFICIENCY IN THE EVALUATION OF TRANSPORT SERVICES FOR DISADVANTAGED PEOPLE

- 6 COMMUNITY-BASED TRANSPORT COORDINATION STRATEGIES: THE UK EXPERIENCE

- 7 DECISION-MAKING PROCESSES IN COMMUNITY TRANSPORT ORGANISATIONS

- 8 THE COMPUTERISATION OF OPERATIONAL DECISION PROBLEMS IN CT

- 9 DEMAND-RESPONSIVE VEHICLE SCHEDULING: GROUPING TRIPS BY FUZZY SIMILARITY

- Index