- 173 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Positive Peer Culture

About this book

This revision of an important and path-breaking work holds to its central argument that troubled young people can develop self-worth, significance, dignity, and responsibility only through commitment to the positive values of helping and caring for others.An enlarged and revised edition of the authors' pioneering work on building positive youth culture, Positive Peer Culture retains the practical orientation that made the original attractive to teachers and youth workers, while adding new material on positive peer culture (PPC) in schools and community settings, research on PPC, and guidelines for maintaining program effectiveness and quality. Concepts of positive peer culture have been applied in a wide variety of educational and treatment settings including public and alternative schools, group homes, and residential centers. Vorrath and Brendtro describe specific procedures for getting youth "hooked on helping" through peer counseling groups, and for generalizing caring behavior beyond the school or treatment environment through community-based service learning projects.The authors contend that the young people who populate our nation's schools are in desperate need of an antidote to the narcissism, malaise and antisocial life-styles that have become so prevalent, and that this book seeks to provide a way of meeting their increasing cry to be used in some demanding cause. On publication of the first edition, Richard P. Barth, Frank A. Daniels Professor for Human Services Information Policy, School of Social Work, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill called Positive Peer Culture "a significant contribution to the field."

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Positive Peer Culture by D.E.C. Eversley in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1 Foundations of Positive Peer Culture

How many things, which for our own sake we would never do, do we perform for the sake of our friends.

—Cicero

The Power of Peers

In most cultures, the training of children begins in infancy and continues until adolescence, whereupon the individual enters the adult role. Even in primitive cultures, this pattern is common and often includes an initiation ceremony, a “right of passage,” to mark the transition from childhood to adulthood.

In modern society, adult status comes many years after adolescence. While a young person achieves physical maturity and wants social independence, he* must remain in a position of dependency. He is compelled to continue in the role of student and is not allowed to compete with adults in the job market. He is out of place in the friendship patterns of adults; he has no legitimate outlet for his newly developed drives; he is not allowed to do the things that adults do for enjoyment and relaxation. Seemingly, society has no role for him, for he is not a child nor is he an adult. So while children “resign” from childhood in their early teens, they do not “enlist” in adulthood until they are fully independent, sometimes as much as a decade later. During this entire period, youth are in a cultural limbo, being neither obedient children nor responsible adults.

Out of their need to be something more than children and to achieve some independence, youth have created their own subculture. Complete with its own values, norms, language, and symbols, the subculture has become so well developed and organized that it spans continents and oceans. The unusual styles of dress and grooming, folk heroes, and slang expressions seem more foreign to the parent who lives under the same roof than to another young person thousands of miles away.

Adults continue in attempts to socialize youth but find they have less and less power, while the youth subculture seems to take an increasingly strong hold. As time goes on, the peer group all but replaces the influence of parents and other adults.

The need of adolescents to conform to peer group norms and values has often been witnessed by youth workers as well as parents. When one refers to the “Tyranny of adolescents” one is expressing an awesome appreciation of the powerful energy and pressures generated by this strange social configuration called the peer group [1].

Adults decry their loss of influence and dream nostalgically of the family of the past where children knew their place and the elders ruled supreme. But it is not possible to turn back the clock to another day when the young person found his peer group among either children or adults. The reality must be accepted as it is: The peer group has the strongest influence over the values, attitudes, and behavior of most youth.

This peer influence might be acceptable if young people were able to succeed at operating their private subculture in a manner that did not cause concern among adults. Unfortunately, society is concerned not only with the lower-class ghetto delinquents but also with many peer patterns formed in the suburbs among young people from seemingly favorable backgrounds. Too seldom we find a peer group composed of young people with values, maturity, stability, and judgment necessary to guide one another into happy and productive roles in the broader society. All too often it seems more like a case of the blind leading the blind, while the supposedly sighted adult stands helplessly on the sidelines.

The various responses of adults in authority to the power of the peer culture merit notice.

Conflict: Perhaps the most universal response is the contest for power. With the motto “we’ll show them who is boss,” adults attempt to instill in the life of the young an obedience that belonged to an earlier time. As controls become restrictive, friction and conflict increase. Adults who feel they are about to lose control frequently send for reinforcements. Parents turn to schools, guidance clinics, and juvenile courts for support. Teachers call for parents to help monitor the cafeteria and for security guards to patrol the hallways. In the end, adults may succeed in applying enough control to impose conformity, but the problems now have gone underground. It is all too easy for the young person to appease the adult with superficial compliance while still remaining basically loyal to different values of his peer group.

Liberation: Another response of adults to the peer group is that of liberation. These adults say: “Go ahead and do your own thing. . . . You are old enough to decide for yourselves.” Such adults may be enthusiastic supporters of “how wonderful today’s young people are”; still they are often troubled by the recurrent feeling that perhaps youth are not yet able to meet all of the challenges of independence.

Surrender: Adults often surrender to the power of the youth subculture. Here the adult experiences feelings of futility. “There’s nothing I can do; they won’t listen anymore.” The young person is left trying to manage his life while the adult ponders just where his approach went wrong.

Joining the opposition: Another variation in adult response to the peer subculture is enlistment in the opposition. Perhaps uttering the trite slogan, “If you can’t beat them, join them,” the adult tries to become like the young person. The adult, struggling valiantly to imitate the youth culture (which never allows grownups as real members), is as completely out of place as he is ineffective.

Enlisting the opposition: This is the response of PPC, which assumes that all of the foregoing styles are inadequate ways of dealing with the peer subculture. Even though the peer group is the most potent influence on youth, adults have much to offer to young people. Furthermore, adults should neither become locked in combat with them nor capitulate to them. Therefore, PPC seeks to encompass and win over the peer group.

An analogy comes to mind. The highly developed Japanese art of jujitsu, when mastered, enables even very small persons to deal with powerful adversaries. It is not necessary to be stronger than an opponent, since force need not be met with force. Rather, the adversary’s strength and movement are channeled into a different direction to achieve the intended result. In the same way, it is not necessary to overcome the peer group’s power; instead, the peer group’s action is rechanneled to achieve the intended goal. Here the analogy ends, for our intention is not to defeat young people but to bring forth their potentials.

Help thy brother’s boat across and lo! thine own has reached the shore.

—Hindu proverb

The Rewards of Giving

In traditional approaches to the problems of youth, adults monopolize the giving of help. In contrast, PPC demands that young people assume the task of giving help among themselves. This notion of helping is, of course, not original; civilized man has long been aware of the benefits that accrue when people are involved in mutual giving. Isaiah expressed this idea nearly 3000 years ago: “They helped every one his neighbor.”

Many organizations flourish mainly because they offer individuals opportunities to serve others. Through the Peace Corps, fraternal groups, volunteer hospital auxiliaries, Big Brother and Big Sister organizations, and the numerous other ways, people assume roles of giving. Those who work in education and the helping professions also derive a great deal of personal satisfaction from contributing to the well-being of others.

Throughout all of our “helping” we have not looked closely enough at the effect of help on the receiving individual. Does being the recipient of help really make a person feel positive about himself? Are we somehow maintaining individuals in helpless and dependent roles? Being helpful usually has an enhancing effect on one’s self-concept; needing help and being dependent on others often worsens the erosion of what may already be a weak self-concept.

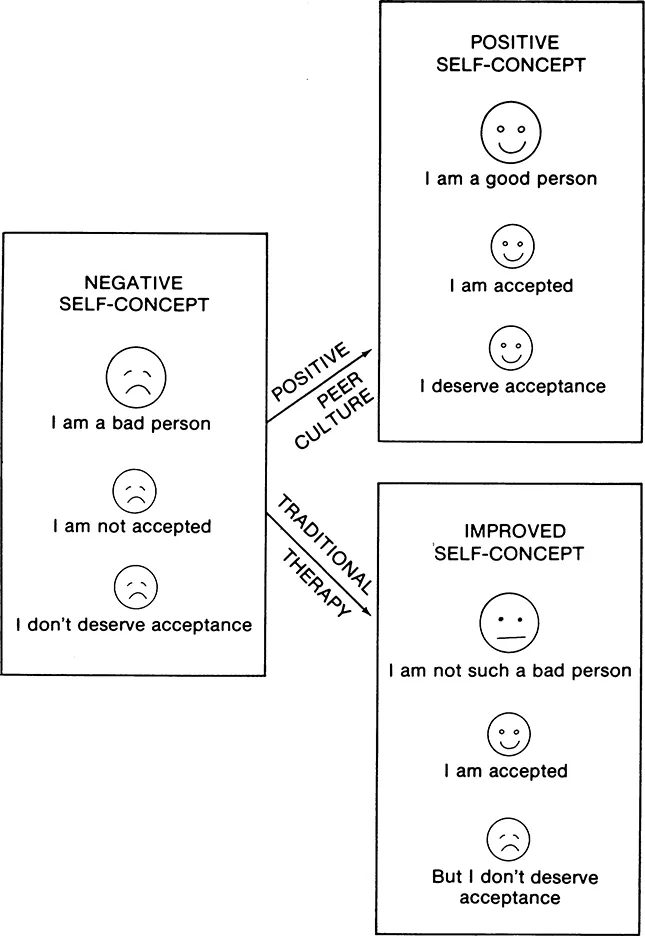

In order for an individual to feel positive about himself, two conditions must exist. First, he must feel accepted by others. Second, he must feel that he deserves this acceptance. Many traditional approaches concentrate on the first condition and overlook the second.

Being accepted: In the past, we have gone to great lengths to tell the troubled person that he is really not so bad as he thinks, that he is worthy as an individual, that he has many fine qualities, and that we accept him. However, just telling someone he is a fine person and treating him kindly is not enough to make the person view himself positively. The person often thinks we are being nice to him only because we feel sorry for him or perhaps even because we are getting paid to be nice.

Deserving acceptance: Despite how others relate to him, a person may feel he is not worthy of acceptance. He knows that much of his behavior is irresponsible and damaging to himself or others, and further, he does not believe he is really making worthwhile contributions to life. If he is to feel deserving of the acceptance, he must start making positive contributions to others and stop harmful behavior.

Figure 1.1 suggests the effects of PPC and traditional treatment approaches on a negative self-concept. Both PPC and traditional approaches strive to make a person feel accepted. However, in traditional therapy an individual often continues irresponsible behavior, and traditional therapy seldom provides the means for one to be of value to others. In contrast, PPC expects that the person will both stop his irresponsible (hurting) behavior and begin helping others. These are the ingredients of a truly positive self-concept.

Contrary to established notions, one need not conquer all of one’s own problems before being able to help solve the problems of others. PPC does not wait until the individual can “cure” all of his own hang-ups before it expects him to contribute to others. Rather, the very act of helping others becomes the first decisive step in overcoming one’s personal problems. In reaching out to help another a person creates his own proof of worthiness: he is now of value to someone.

Figure 1.1

Effects of PPC and traditional treatment approaches on negative self-concept.

It is widely assumed that a primary determinant of success in therapy is that the person be able to ask for help, admitting to his inadequacy and need for assistance. In fact, our experience has indicated that the individual whose approach to us is “Please rehabilitate me” or “I think I need help and I feel you can help me” may be in worse trouble than the one who denies the need for help. Most often such an approach tells us one of two things: (1) this is a weak, helpless, ego-deficient individual who is all too ready to surrender to his own inadequacies, or (2) this is a con artist telling the therapist what somebody seeking help is supposed to say. Neither of these possibilities speaks well for the person’s prospects for change.

The young person who tells us “You are not going to get me to change” is not saying he is unwilling to change. In reality, most youth are considerably more receptive to change than are older individuals. What such a person is really saying is that “I am not going to be changed by you,” a very different situation. Young people do not resist change: They only resist being changed.

Rather than hoping the youth will come forth with a “cry for help,” PPC asks first that he be willing to offer help to others. While an individual certainly must learn to receive as well as to give help, the balance must be weighted in favor of giving—the only route to true strength, autonomy, and a positive self-concept. In PPC, the entire process of helping others is given highest status. The young person does not have to be cured because he is mentally ill, punished because he is immoral, or enlightened because he is ignorant. Rather, he comes to help others and thereby to receive help with his own problems.

He who helps in the saving of others saves himself as well.

—Hartmann von Aue

The Strength of the Reformed

The person who has successfully overcome adversity and resolved problems often has great potential for understanding the problems of others and helping them to master similar difficulties. This principle has not found widespread application except in isolated instances, most notably in Alcoholics Anonymous. In this organization, the fight against alcoholism is not waged by professionals trained in the characteristics and treatment of alcoholics; rather, it is the reformed alcoholic who is the core and power of such a program. The most potent influence on the alcoholic is that exerted by another alcoholic. As the reformed individual attacks what he once embraced, he both directs others away from involvement and counteracts his own tendencies to resume such behavior. This powerful treatment concept has been little understood except by those who have directly experienced its impact.*

When working with troublesome youth, we all too often see only their limitations and not their strengths. The traditional mental health view is that behavior problems result from emotional disturbance or mental illness. Since these youth have experienced much conflict, neglect, and rejection, we assume that somehow they were severely damaged and weakened by such experiences. In reality, the tremendous pressures in the lives of these troubled youth have in some respects made them stronger than many “normal” youngsters. What “normal, well-adjusted child” would even dare to simultaneously challenge parents, principals, and...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- From One Delinquent to Another

- Introduction

- 1 Foundations of Positive Peer Culture

- 2 Issues in Positive Peer Culture

- 3 Demanding Greatness Instead of Obedience

- 4 Identifying Problems

- 5 Assigning Responsibility for Change

- 6 Implementing a Positive Peer Culture

- 7 Staff Roles and Responsibilities

- 8 The Group Session

- 9 Cultivating a Caring Culture

- 10 Organization in Residential Settings

- 11 Positive Peer Culture in School Settings

- 12 Evaluating Positive Peer Culture

- Index