- 236 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

A Historical Geography of China

About this book

The Chinese earth is pervasively humanized through long occupation. Signs of man's presence vary from the obvious to the extremely subtle. The building of roads, bridges, dams, and factories, and the consolidation of farm holdings alter the Chinese landscape and these alterations seem all the more conspicuous because they introduce features that are not distinctively Chinese. In contrast, traditional forms and architectural relics escape our attention because they are so identified with the Chinese scene that they appear to be almost outgrowths of nature. Describing the natural order of human beings in the context of the Chinese earth and civilization, "A Historical Geography of China" narrates the evolution of the Chinese landscape from prehistoric times to the present.Tuan views landscape as a visible expression of man's efforts to gain a living and achieve a measure of stability in the constant flux of nature. The book ranges the period of time from Peking man to the epoch of Mao Tse-tung. It moves through the ancient and modern dynasties, the warlords and conquests, earthquakes, devastating floods, climatic reversals, and staggering civil wars to the impact of Western civilization and industrialization. The emphasis throughout is on the effect of a changing environment on succeeding cultures.This classic study attempts to analyze and describe traditional Chinese settlement patterns and architecture. The result is a clear and succinct examination of the development of the Chinese landscape over thousands of years. It describes the ways the Communist regime worked to alter the face of the nation. This work will quickly prove to be crucial reading for all who are interested in this pivotal nation. It goes far beyond the usual political spectrum, into the physical and social roots of Chinese history.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

The Role of Nature and of Man

Chapter 1

Nature: landforms, climate, vegetation

Since our main concern is to trace some of the changes over the face of the Chinese earth wrought through human agency, it is usual to start with a section on the natural setting. The state of nature before the arrival of man is often conceived to be - at least implicitly - in a condition of quasi-equilibrium. Man appears, and through his power for action, upsets the quasi-equilibrium and progressively transforms the primordial state so that eventually, in places, an entirely artificial world is superimposed upon it. A slightly different way of characterizing this view is to describe nature as the 'stage' or the 'setting', and man as the 'actor'. Nature is assumed to be stable and given a passive role. Man is the free and active agent. As a position that one may provisionally accept in order to follow a special line of inquiry it has great value: however, for China the acceptance of a too rigid dichotomy runs the risk of unnecessarily warping reality. Nature in China has not been notably stable. It cannot be viewed simply as the passive, immobile stage. This is evidently true if we take a broad time span so as to include human prehistory, and it remains a relevant fact even if we restrict ourselves to the recorded period.

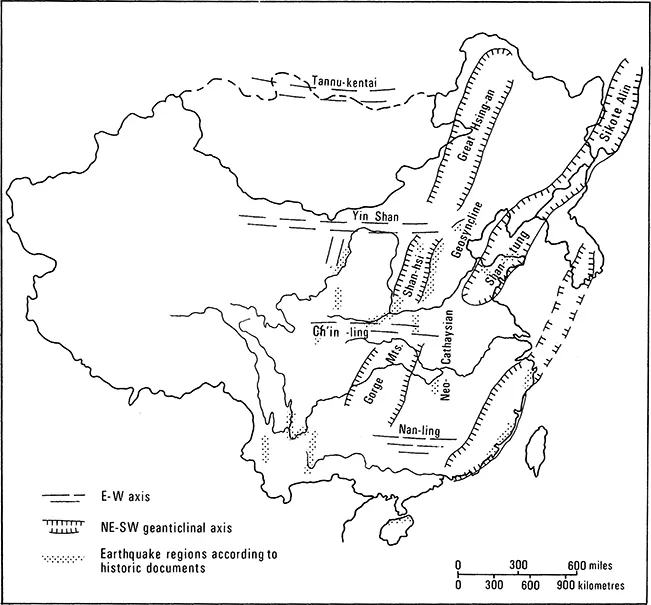

The chequerboard pattern: tectonics and landforms

China's physique has been described as resembling a chequerboard. Even a brief study of a good relief map supports this characterization. In western China we can easily discern the juxtaposed units of plateaux and basins separated by narrow, sharply demarcated mountain chains. In eastern China the units of the chequerboard are perhaps less clear but several are outstanding, as, for example, the well-defined central Manchurian plain, the North China plain, the lake basins of the central Yangtze Valley, and the Ssu-ch'uan basin; even the great northern loop of the Huang Ho is suggestive of a chequerboard unit. This basic physiographic characteristic of the Chinese land mass appears to be the result of the intersection of two major sets of structural lines: one set extends from northeast to southwest, the other - less well defined topographically - displays an east to west trend. The structure of China, viewed as the complex interplay of several distinctive tectonic areas, was clarified by the generalizations of J. S. Lee (S. K. Li).1 In what follows we shall describe present landforms in the framework of the major structural trends, for this procedure will allow us to proceed towards an understanding of the landforms as something other than a catalogue of set pieces in the earth's crust.

Consider first the northeast to southwest trends. They may be seen as a succession of upfolds (geanticlines) and downfolds or geosynclines in the earth's mantle. The upfolds produce mountain chains and islands, the downfolds the seas, the plains and basins. These together form concentric arcs on the eastern border of the Asian continent. Beginning from the east, the first of such trend lines is a geanticline which finds topographic expression in the islands of Japan, the Ryukyu islands and Taiwan. Westward is a depressed segment of the earth's crust, covered in varying depth by water: the Sea of Japan, the East China Sea and Taiwan Strait are the main units. On the edge of the Asian mainland we encounter another complex upfold which begins with the mountain ranges of Sikhote Alin in the Soviet Union and continues south-westward into the Liao-tung and Shan-tung peninsulas. A branch, or perhaps a separate unit, of the geanticline appears at the south end of the Korean peninsula and reappears, across the sea gap, in southeast China. The alignment of the main mountain ranges in these upfolded zones reflects the general structural trend except where the trend is interrupted by major cross-faulting, as in Shan-tung peninsula, and, of course, where it appears to be completely broken and dips under the sea. In detail, the landforms of the geanticlines show great diversity, since they depend not only on structure but also on the rock material, and on the intensity of weathering and erosion. Thus the Liao-tung peninsula and the east Manchurian highland lie mostly under 3,000 feet, are hilly rather than mountainous, and have a local relief of only a few hundred feet. In contrast the mountains of southeastern China, though not much higher, are much more rugged. The granite and volcanic rocks have, under tropical climate, yielded steep, dramatic forms; these, when wrapped in mist and appropriately crowned by Buddhist monasteries of the Ch'an sect, evoke the full flavour of Chinese landscape painting.

The chief lowland of China corresponds to a down warped strip of the earth's crust (Fig. 4). It extends from northeast to southwest, and is rimmed by highlands except for two breaks in the geanticline on the eastern side: one is the narrow neck of water, dotted with islands, that separates the Liao-tung peninsula from the Shan-tung peninsula. Another is the low coast between Shan-tung and the northeastern terminus of mountains in southeast China. The lowland is made up of three units, set apart from each other by mountain barriers, the Jehol block in the north and the Ta-pieh block in the south. The surface characteristics of these three pieces of lowland are quite distinct. The northernmost, the central Manchurian plain, is an erosional surface. It is therefore well drained for the most part, and gently rolling, not flat. The central piece, the North China plain, was built up by successive layers of alluvium. It is nearly flat. Gradient to the sea is so gentle that large areas, even in the recent past, were seasonally covered by sheets of water or were otherwise ill drained. One reason why floods on the North China plain brought such prolonged economic hardship to the peasants was the slowness with which the flood water could be led off. A bizarre though not exceptional scene in North China was to see a walled city that rose out of a broad sheet of water, and to see farmers fishing in their flooded fields outside the city walls. Yet normally the North China plain, especially on a windy, dust-laden day in winter, looks brown and parched. Its summer rainfall is only just sufficient for its dry crops. The wettest and most low-lying of the three segments of the lowland is the southernmost. It is made up of the lake basins of the central Yangtze Valley, and has the appearance of a new earth recently born of a watery chaos. Standing on the shores of either the Tung-t'ing or Po-yang lake one could well imagine oneself to be at the edge of the ocean.

4. Chequerboard pattern and structural axes of China. (After Lee).

To the west of this sunken strip of lowland is the most prominent of the northeast to southwest geanticlinal axes. Its main units are the Great Hsing-an Mountains in Manchuria, the Shan-hsi plateau, and the Gorge Mountains across the Yangtze Valley. The Great Hsing-an Mountains separate the two treads of a step-like structure: the higher tread is the Mongolian plateau, and the lower one the central Manchurian lowland. Seen from the lower tread the Hsing-an rises prominently as a scarp. But seen from the higher tread the crest of the scarp is merely a treelined swell on the horizon. The T'ai-hang Shan on the eastern border of the Shan-hsi plateau stands even more sharply above the alluvial surface of the North China plain. The plateau itself is made up of a series of folds complicated by faulting. One down-faulted strip finds topographic expression as the Fen Ho Valley.2 The Gorge Mountains, too, are an accordion of folds, only here the Yangtze Chiang transects dramatically the northeast to southwest trend of the mountains to produce a series of stupendous defiles. The river emerges from the defiles at I-ch'ang. For a short distance downstream it remains confined between terraces but it eventually swings free in the watery landscape of the Tung-t'ing lake basin.

West of the axis of the Hsing-an and Gorge Mountains, three areas of relatively lower relief and elevation may be discerned: the Mongolian plateau, the Shen-hsi plateau with adjoining Wei Ho Valley, and the Red basin of Ssu-ch'uan. These are separated by two of the east to west axes that transect the more striking physiognomy of the northeast to southwest trends. The Yin Shan east-west axis appears as a low range separating the Gobi desert from the Ordos desert and Shen-hsi plateau to the south. The Ch'in-ling east-west axis, however, is one of the sharpest boundaries (floristic, faunal, and human) in the geography of China. Where it separates the Shen-hsi plateau from the Red basin of Ssu-ch'uan its crest stands at about 7,000 feet. The northern flank of the range rises as a mountain wall above the Wei Ho Valley. The sharp physiographic contrast expresses a structural relationship, for the Ch'in-ling wall is a complex faultline scarp overlooking the sliver of earth crust, the Wei Ho trough, that has been let down.3 The Red basin to the south lies encircled within a curtain of mountains. It is one of the more distinctive pieces within the Chinese chequer board. In contrast to the North China plain and the central lake basins, the treads to the west of the Shan-hsi plateau and Gorge Mountains axis are not flat. Both the Shen-hsi plateau (which is structurally a basin) and the Red basin have high local relief. To their west the lineaments of structure become harder to decipher.

It will be noticed that the concentric belts of northeast to southwest upfolds and depressions do not appear to continue into South China, except for the mountains of the southeast coast. Structure and topography lack the simple relationship that they have in the central and northern parts of the country. The Nan-ling east-west axis has no evident surface expression; and the most distinctive landform in southwest China is the result of rock material rather than structure. This is the landform of discrete mountain peaks and rock spires that have developed through the weathering and denudation of limestone.

The relief pattern of China has been characterized as chequer board. It can also be described as having two distinct parts, West and East. The western part of China contains the Tibetan plateau, one of the highest in the world, as well as high mountain ranges, such as the Kun-lun, the T'ien Shan and the Altai, that have no match in the East. Among these elevated plateaux and mountains of the West are almond-shaped depressions or basins of east-west orientation; for example, the Dzungarian, the Tarim, and the Tsaidam. Eastern China is lower and descends to the sea through a series of giant steps separated by rises that trend from northeast to southwest. The overall gradient of China is from west to east, and this fact is emphasized by the direction of flow of the three main rivers, the Huang Ho, the Yangtze Chiang, and the Hsi Chiang.

The unstable earth

Tectonic and hydrologic changes in western China

The framework I have thus described is not set in rigidity. It is not an immobile stage on to which we can usher the human actors. Its components are subject to slow movements and sudden shifts. Such had been the case throughout the second half of the Pleistocene epoch when man appeared on the Chinese scene and added his capacity to alter to that of geophysical agents. But even in the period of recorded history, movements of rock and shifts in water course continue; together with human efforts they account for the persistent and changing aspects of the Chinese earth.

Sinanthropus pekinensis (H. erectus pekinensis) or Peking Man appeared on the Chinese stage sometime in the Middle Pleistocene epoch, probably some 300-500,000 years ago. Through his knowledge of the use of fire, Peking Man was the first hominid in China to have had the power to alter significantly the biotic cover of his homeland. Let us consider some of the natural changes in landscape that have taken place since Peking Man first appeared. A major change was the broad uplift of the Tibetan plateau. Its present height appears to be a late achievement. The last rise of some 8,000 feet may have taken place only in the second half of the Pleistocene.4 One consequence of the rise was to cut off the moisture brought in from the Indian Ocean by monsoonal winds. The numerous lakes of the Tibetan plateau are all shadows of their former selves: some are surrounded by terraces that stand almost 200 feet above the present water-level. It is possible that the rise of the Himalayan barrier has contributed towards the desiccation of the plateau.5 Another consequence of the uplift was that it increased the gradient of the rivers that flowed off the borders of the plateau, enabling them to incise into the plateau and produce gorges and canyons without parallel for length, depth and density in the world.

The canyons at the southeastern edge of Tibet, clothed in dense vegetation, provided an effective barrier between the Indian and Chinese civilizations. The rivers are still cutting down rapidly. The deepening of the canyons is not at an end. And indeed the Tibetan plateau has not yet achieved stability: seismic disturbances along the length of the Himalayas, capable of bringing disaster to foothill settlements, are indicative.

To the north of the Tibetan plateau is the Tarim basin. This is the driest area in the Chinese domain, the dryness being accounted for by its continental location but even more by the fact that, except for the opening to the east, the Tarim basin is rimmed by high mountains and plateaux. At the centre of the basin lies a great expanse of sterile sand, known as the Takla Makan desert. Yet, in the Ice Age, not sand but the waters of a large glacial lake occupied much of the basin floor. The western part of the lake was soon filled with sediments, but eastwards open water persisted long enough to produce a beach line on the flank of the Quruq Tagh (Dry Mountain). The beach line, however, is tilted. It slopes eastwards at an appreciable gradient. As a result of the tilt the lake was displaced to the east, forming a new lake in approximately the area of the present Lop Nor basin.6 The precise dates for these major alterations of hydrography and topography are not known but they very probably took place towards the end of the Pleistocene. If this still sounds remote, we may add that changes in hydrography, of a kind to affect the fate of settlements and trade routes, were known to have occurred in historic times and are indeed a present possibility. The effect of changes in water course on settlement may be seen, for example, in the fate of Lou-Ian, to the west of Lop Nor.7 Lou-Ian was at one time an important settlement on the trade route between China and Western Asia. Its solidly constructed fortresses, temples, stupas and houses were located along the distributaries of a delta that terminated in Lop Nor. The river that brought water to Lop Nor and served as the lifeline of the settlement was the Tarim. However, sometime during the second quarter of the fourth century A.D. the Tarim River changed its course; it swung to the south and fed into another lake. Lou-Ian soon had to be abandoned. This is not the end of the story, for sometime in the early decades of the twentieth century, a branch of the Tarim River resumed its old course, and brought enough water to the Lop Nor basin to give it a new lease of life.8

Loess in the middle Huang Ho basin

In eastern China natural changes of landscape since the Middle Pleistocene were caused by phases of deposition and erosion, and by tectonic adjustments along the main structural axes. Deposition is clearly and widely recorded in North China. During the Middle Pleistocene the most common type of deposit consisted of red slope-wash clays and thick red loamy alluvium. Limestone caves, including those inhabited by Peking Man, were thus filled. After An inn and hut stand by a ravine and not by a delta. They are in the ravine to be near the water; they are not by the delta because of the danger & short phase of erosion, deposition was resumed. The material this time was a fine loamy silt laid by wind and known as huang tu (yellow earth) or loess.

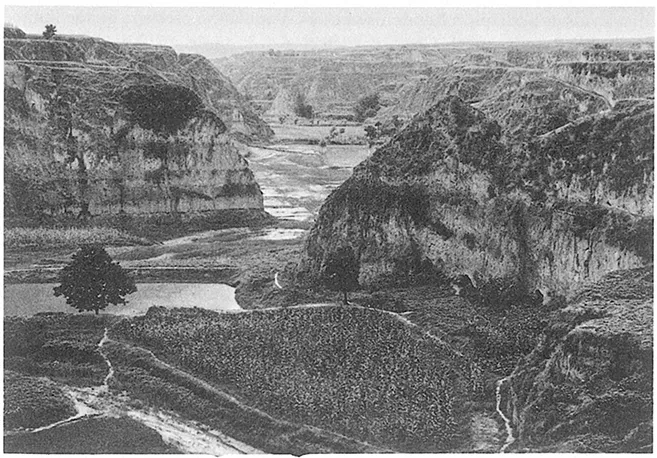

5. Loess topography

Deposition of loess began sometime in the Upper Pleistocene, perhaps under the cool dry, conditions that pertained in the interior of Asia during the last glaciation. Strong winds from the interior brought fine dust southwards and banked them against the mountain ranges and plateaux of western and northern China. Small patches of loess are known to occur on the high flanks of the Kun-lun Mountains. Dust from the floor of the Tarim basin is trapped there, and later returned to the basin by streams as pockets of loessical alluvium of great fertility.9 Farther east, loess is banked against the northern slopes of the Nan Shan in Kan-su province; and when redeposited by streams in the adjacent lowlands they produce oases of rich soils. But the thickest and most widespread blanket of loess appears in North China roughly to the south of the line of the Great Wall. They drape over the hills and basins of eastern Kan-su, Shen-hsi and Shan-hsi provinces, forming here a thin veneer, there a thick cover that submerges an older, eroded topography.10 In northern Shen-hsi province and in the valleys of southeastern Kan-su loess locally attains a thickness of more than 250 feet. Over the more ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Editor’s Preface

- List of Illustrations

- Introduction

- Part One THE ROLE OF NATURE AND OF MAN

- Part Two LANDSCAPE AND LIFE in CHINESE ANTIQUITY

- Part Three LANDSCAPE AND LIFE IN IMPERIAL CHINA

- Part Four TRADITION AND CHANGE IN MODERN CHINA

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access A Historical Geography of China by Yi-Fu Tuan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historical Geography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.