![]()

Part II

On Energy and Momentum

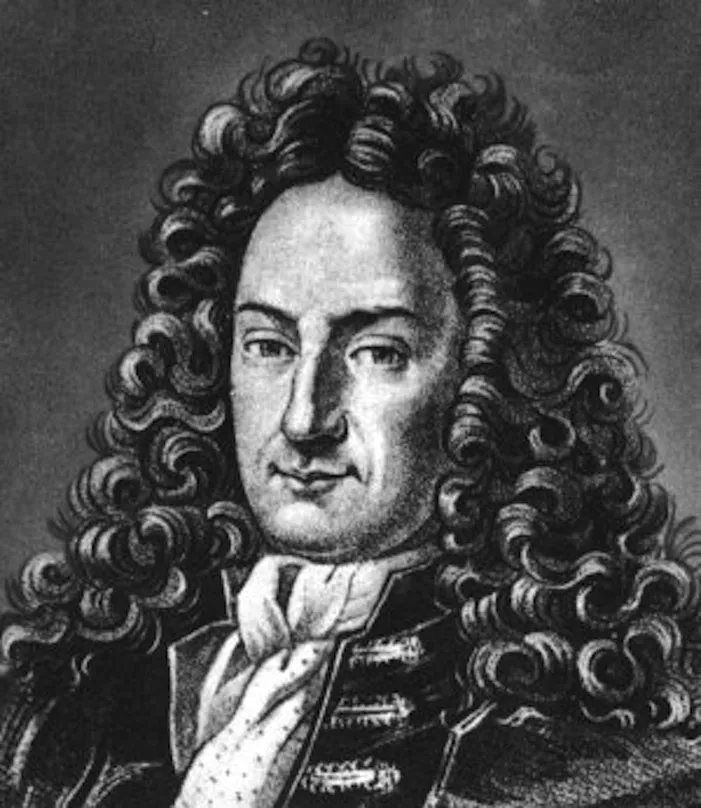

In November 1715, just a year before his death, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (July 1, 1646–November 14, 1716) set down a fundamental challenge to his British rival Isaac Newton (1642–1727):

Sir Isaac Newton and his followers have … a very odd opinion concerning the work of God. According to their doctrine, God Almighty [needs] to wind up his watch from time to time; otherwise it would cease to move. He had not, it seems, sufficient foresight to make it a perpetual motion…. [He] is obliged to clean it now and then by an extraordinary concourse, and even to mend it as a clockmaker mends his work.1

For Leibniz, Newton’s God was a clockmaker, engineer, and mathematician who lacked the foresight to create a perfectly functioning machine at the creation of the world and had to use his power to repair a clock that ran down and whose planetary orbits could be disrupted by passing comets.

This colorful statement, which initiated the famous Leibniz-Clarke debate of 1716 on the nature of God (with Samuel Clarke speaking for Newton), was actually the apex of one of the most profound and divisive debates in the history of physics—the controversy over living force (vis viva), or conservation of energy. Leibniz had started the whole matter in 1686 with a paper arguing that “force” should be measured by mv2 (living force) now known as kinetic energy (½ mv2) and not by the “quantity of motion” m|v| (or when direction is considered as mv, mass times velocity—now known as momentum). In Part II, I present the interlinking physical and metaphysical arguments of Leibniz, Newton, and d’Alembert, the third of whom allegedly resolved the debate in 1743, although as I show in Chapter 6, it lingered on for many years afterward.

In Chapter 4 on Leibniz, I argue that Leibniz’s early insight into a universe that is fundamentally alive, vitalistic, and energistic underlay his efforts to define force as vis viva and describe it as mv2. “Force” for Leibniz is a momentary state that carries within it a tendency toward a future state—what in 1714 he christened as the monad. Force is a striving, a conatus that has direction and is future-oriented. What is real in nature is activity, not extension as Descartes had argued. It is living force—mv2—that is conserved in the universe. Leibniz’s insight was later incorporated into the general law of the conservation of energy, also known as the first law of thermodynamics, which posits that the total energy in the universe (considered as a closed system) can neither be created nor destroyed; it is only changed in form.

In Chapter 5 on Newton, I place the vis viva controversy within the opposing views of Newton and Leibniz on natural philosophy, including the nature of God, matter, and force as represented by mv versus mv2 and show that adherents to the two systems developed such intense loyalties to the two founders that they were blinded from seeing that both laws and both systems had validity. I ground their differing ideologies within the intellectualist versus voluntarist theological frameworks of the medieval period; the opposition between views of matter as dead, lifeless, and inert versus matter as point sources of force, alive, and energetic; and differing views as to whether the total “force” (energy) in the universe was constant and conserved or whether the universe could run down, requiring God’s intervention to “rewind his clock.” Indeed just as Leibniz’s insight about the conservation of vis viva anticipated the first law of thermodynamics or general law of the conservation of energy, so Newton’s intuition about the universe running down anticipated the second law of thermodynamics that order moves to disorder as the entropy of the universe (the energy unavailable to do work) increases, resulting in what was then considered to be a cosmic heat death.

Chapter 6 on d’Alembert argues that although the controversy over living force has often been considered to be resolved in 1743 when d’Alembert said that both mv and mv2 were correct measures of “force,” for a number of reasons, this date has little meaning. Scientists continued to prefer either mv or mv2 when trying to solve problems of the interaction of bodies. It was not until the late nineteenth century that equal status was given to both the conservation of kinetic energy and momentum.

Together, these three chapters show that the controversy over living force was at the root of some of the most complex physical and metaphysical issues of early modern science. They demonstrate that critical linkages exist among assumptions about the nature of matter, energy, causality, order, disorder, and the properties and even existence of an ultimate deity. Science does not exist as an “objective,” orderly system of discovering and demonstrating the truths of nature. Rather it is often a messy process, driven by chance, by assumptions that later prove incorrect, by intense loyalties, and by failures to recognize valid arguments and experiments. As these chapters demonstrate, science, in the process of reaching agreement and ultimately getting to “yes,” can at times appear muddled, chaotic, disorganized, and confused even as it carves out pathways toward the laws of nature.

Note

![]()

4

Leibniz*

Figure 4.1 Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716). Copper engraving, 1775, by Johann Friedrich Bause (1738–1814), after a 1703 painting by Andreas Scheits (ca. 1655–1735).

In 1686, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) publically set down some thoughts on René Descartes’ mechanics. In so doing, he initiated the famous dispute concerning the “force” of a moving body known as the vis viva controversy. Two concepts, now called momentum (mv) and kinetic energy (½ mv2), were discussed as a single concept, “force,” each differing from Newton’s idea of force. One of the many underlying problems of the controversy was clarified by Roger Boscovich in 1745 and Jean d’Alembert in 1758, both of whom pointed out that vis viva (mv2) and momentum (mv) were equally valid.1

The momentum of a body is actually the Newtonian force F acting through a time, since v = at and mv = mat = Ft. The kinetic energy is the Newtonian force acting over a space, since v2 = 2as and mv2 = 2mas or ½ mv2 = Fs. Although confusion over these two definitions is apparent in the various arguments of the contenders, many other sources of confusion entered into the debates. Some of these factors are clarified in the following discussion of the early years of the vis viva controversy.

The controversy had its roots in Descartes’ law of the quantity of motion, as discussed in his Principia philosophiae of 1644.2 It was Descartes’ belief that God, the general cause of all motion in the universe, preserves the same quantity of motion and rest put into the world at the time of creation. The measurement of this quantity is mv, implied in the statement “we must reckon the quantity of motion in two pieces of matter as equal if one moves twice as fast as the other, and this in turn is twice as big as the first.”3 The conservation of quantity of motion is derived from God’s perfection, for He is in Himself unchangeable and all His operations are performed in a perfectly constant and unchangeable manner. There thus exists an absolute quantity of motion that for the universe remains constant. When the motion in one part is diminished, that in another is increased by a like amount. Motion, like matter, once created cannot be destroyed because the same amount of motion has remained in the universe since creation. It is evident from Descartes’ application of the principle in his rules governing the collision of bodies that this quantity mv conserves only the magnitude of the quantity of motion and not its direction; that is, velocity is always treated as a positive quantity, |v| rather than as a vector quantity whose direction is variable. Beginning in 1686, Leibniz wrote a series of papers objecting that the quantity that remains absolute and indestructible in nature is not quantity of motion m|v| but vis viva, or living force, mv2.

Shortly before this, in 1668, John Wallis, Christopher Wren, and Christiaan Huygens had presented papers to the Royal Society showing that the quantity conserved in one-dimensional collisions was not m|v| but m v, where the sign of the velocity is taken into consideration.4 Wallis discussed hard-body inelastic collisions and Wren described elastic collisions. Huygens used rules equivalent to conservation of mv and mv2 for elastic impacts. Leibniz was well acquainted with these contributions; he had discussed them in his own notes as early as 1669 and mentioned them in his Discours de metaphysique5 published in 1686. He was thus aware of the distinction between quantity of motion m|v| and the quantity later called momentum, mv. Leibniz referred to momentum conservation as conservation of total progress (l69l).6 His arguments against Descartes beginning in 1686 were thus designed to establish the superiority of mv2 over m|v|, not over m v.

During the ensuing vis viva controversy, several concepts were confused in the arguments between Leibniz and the Cartesians. The concepts under discussi...