What do we mean by inclusion?

’Inclusion’ is undoubtedly the buzz word of the decade. Everywhere you turn there are policies and mission statements about services and organisations becoming ever more inclusive. With each group using the term in its own way, it is not surprising that people are becoming confused. Even within the educational world, interpretations of what exactly is and isn’t inclusive education vary widely and many have very little to do with equality of opportunity or universal access to mainstream education. For the purposes of this book, the term ‘inclusion’ will be used for the successful mainstreaming of pupils with special educational needs (SEN) who would traditionally have been placed in special schools. Our emphasis will be on celebrating diversity and responding positively to the challenges that are presented.

Mercia prides itself on being an inclusive local education authority (LEA). The majority of pupils with statements are supported in their local mainstream school. At the same time, it has a well funded and highly regarded network of special schools for pupils with severe learning difficulties. Pupils are assessed preschool, and on the basis of their ability are offered either a mainstream or a special school place. Tom’s parents accept that he has severe learning difficulties, nevertheless they are convinced that he should attend a mainstream school. After approaching seven local schools who all said ‘no’, they found a welcoming school. Despite this, the LEA held their position and insisted that special school was the only appropriate placement.

Q. Is this a truly inclusive LEA?

A. No it isn’t. In any inclusive system, all children are valued equally and are welcomed into the mainstream. Their school place is theirs of right and is not conditional on their level of need.

Hampton LEA state in their mission statement their commitment to inclusive education. While a high proportion of pupils with statements continue to be placed in segregated settings, the LEA has devolved Standards Fund money to their special schools to enable as many children as possible to attend a mainstream school on a parttime basis, thus getting ‘the best of both worlds’. Each child on the programme attends a mainstream school for a maximum of one half day per week.

Q. Is this inclusion?

A. No it isn’t. Children who are included should be on the roll of a mainstream school and attend on a full-time basis.

Niamh is very small for her age and is significantly delayed in her development. At four she was not yet toilet trained, so her school decided to keep her down in the nursery. At six she was only speaking in single words and was working towards Level 1 of the National Curriculum, so she was kept down again. At eight she is still in a class of five-and six-year-olds. At her last review, the school was pleased to report that she now fitted in so well, both academically and socially, you hardly knew she was there.

Q. Is this inclusion?

A. No it isn’t. If children are to gain a sense of their own identity and benefit from age-appropriate models of learning and behaviour, they must mix regularly with typical peers of their own age. Keeping children down may seem to solve an immediate problem, but it is likely to cause greater difficulties in the long term.

Tariq is a bright little boy with Down’s Syndrome. In his LEA, children like Tariq who are assessed as having ‘moderate learning difficulties’ are placed in a resourced mainstream school. Each morning Tariq registers in the special unit and then, after sitting with the other unit children during assembly, spends the rest of each morning withdrawn for literacy and numeracy. Since his special taxi rarely arrives at school before 9 a.m. there is no time for him to play with his mainstream friends before school. While he joins with typically developing peers for music, art and PE, he is not with them every day because some days there is no one available to support him in class, so he goes back to the unit.

Q. Is Tariq being included?

A. No he isn’t. As full and equal members of the school community included pupils should be given the opportunity to learn and play alongside their mainstream peers for most of the school day.

Ricardo is profoundly deaf and relies on British Sign Language as his primary form of communication. He has settled well into Year 7 of his local high school with in-class support from a signing interpreter. At the school’s open evening for prospective new pupils, Year 7 pupils were invited to attend and to befriend a visiting student, showing them round the school. Because of possible communication problems, the school decided it would be unfair on Ricardo to ask him to do this. No one consulted him or his parents -he just didn’t get an invitation.

Q. Is this inclusion?

A. No it isn’t. As a member of the school community, an included student should have the opportunity to participate fully in the non-curricular life of the school as well as in the academic curriculum. The issue isn’t whether he should participate, but what support he needs to enable him do so.

Tamara is partially sighted and attends her local secondary school where she is doing well academically. However, she is finding it difficult to get around the large campus and to cope on crowded staircases. Her parents have asked for additional mobility training and for her to be let out of lessons early. These requests have been refused as the school say that inclusion means being treated the same as everyone else.

Q. Are they right?

A. No they aren’t. While included children should have full access to the curriculum and the life of the school, inclusion does not mean that their individual needs are ignored or special help refused.

Sally has cerebral palsy. To make her local secondary school fully accessible would have involved time and effort as well as some additional expenditure, which the school was reluctant to commit, so she was offered a place in a newly adapted school 15 miles from her home. Each morning she is collected by taxi and taken to school. Her friends all live around the school so she never sees them in her local shops or in the park at weekends. When it was her birthday, she invited all the girls in her tutor group to her party. Sadly, hardly anyone could come, as few of their parents have cars and local bus services are poor.

Q. Is Sally being fully included?

A. No she isn’t. Effective educational inclusion should lead to community inclusion. Wherever possible, an inclusive school placement should allow young people to make relationships with others from the area where they live. Ideally they should go to their local school. Where this is not a realistic option, they should always be offered a school within reasonable travelling distance of home.

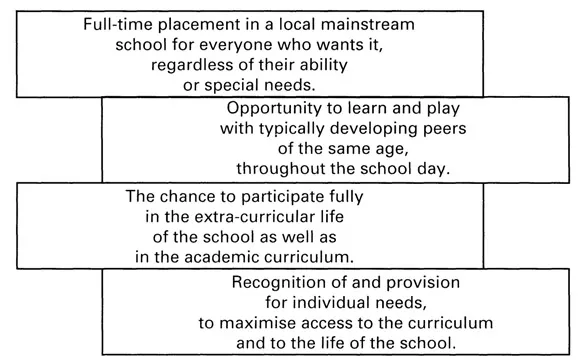

So what is truly inclusive education? (See Figure 1.1)

Figure 1.1 What is inclusive education?

What the law and the government say

Until January 2002 LEAs and schools were working to the requirements of the Education Act 1996, while having regard to the Code of Practice on the Identification and Assessment of Special Educational Needs (Department for Education and Employment (DfEE) 1994). Within the law as it stood, the LEA had a qualified duty to ‘secure that the child is educated in a school that is not a special school unless that is incompatible with the wishes of his parents’. They could only deny a parental preference if they believed the school was unable to meet the child’s needs, or would be incompatible with the education of other children or the efficient use of resources.

Before naming a school, the law also stated that the LEA must consult the governors. Guidance from the Code of Practice noted that: ‘the LEA should give due consideration to the views expressed by those consulted, but the final decision as to whether to name the school falls to the LEA’. Despite this, LEAs rarely considered it appropriate to override the governors and direct reluctant mainstream schools to admit pupils with a statement of SEN.

The Code of Practice undoubtedly provided a framework within which inclusion could be promoted. But it soon became clear that it could do little on its own to change entrenched positions. The newly elected Labour Government of 1997, therefore, with its professed commitment to increase inclusion, set about reviewing practice. In its consultation document Excellence for All Children: Meeting Special Educational Needs (DfEE 1997) it states:

We want to see more pupils with SEN included in mainstream primary and secondary schools. By inclusion we mean not only that pupils with SEN should wherever possible receive their education in a mainstream school, but also that they should join fully with their peers in the curriculum and life of the school.

For example, we believe that… children with SEN should generally take part in mainstream lessons rather than being isolated in separate units.

Regrettably, this document said nothing about the need for children to attend a neighbourhood school, which would allow them to make friends in their local community. Nevertheless, it went a lot further than previous government publications in encouraging more inclusive practices. It went on to say that for children with complex needs, the wide variation in opportunities to attend a mainstream school found across the country was unacceptable. In extolling LEAs to adopt more inclusive practices, it was encouraging to see the department stressing that ’It is not good enough simply to say that local mainstream schools have not previously included a child with these needs’ as an excuse for failing to include a particular child. Instead the challenge was ‘to identify the action that would be required and by whom, to make it happen’.

As well as looking at ways of fostering inclusion, the Programme of Action (DfEE 1998a) which followed the consultation document considered a range of other issues in SEN practice, including a revised Code of Practice which was first issued in draft form in July 2000. The aim was to have the new Code in place by September 2001. Although the time scales slipped somewhat, along with those for the publication of the SEN and Disability Act 2001, it eventually appeared in its final form in October 2001, with implementation in January 2002.

Both documents are likely to make a significant contribution to the inclusion debate. Within the new Code of Practice (DfES 2001), there is a clear statement that ‘the Government believes that when parents want a mainstream place for their child the education service should do everything possible to try to provide it’. They go on to say that ‘All schools should admit pupils with already identified special educational needs … Admissions authorities for mainstream schools may not refuse to admit a child because they feel unable to cater for their special educational needs’.

This is a powerful statement, although in itself it has no real ‘teeth’. However, the SEN and Disability Act now takes this somewhat further. In Part 1, the bill amends section 316 of the Education Act 1996 to state that a child with a statement of SEN: ‘must be educated in a mainstream school unless this is incompatible with:

- (a) the wishes of his parent; or

- (b) the provision of efficient education for other children’.

Further, the Act states that an LEA can only rely on exception (b) ‘if they show that there are no reasonable steps that they could take to prevent the incompatibility’. Even though this is somewhat less than the proponents of full inclusion had hoped for, it should be sufficient to allow more parents to succeed within the (SEN) Tribunal system in gaining an inclusive placement. Certainly it should no longer be possible for LEAs to say no to inclusion without making any effort to identify a suitable mainstream school, to work positively with school staff or to put in place the provision required to make the placement viable.

The effectiveness of any inclusive placement is, however, just as important as the placement itself. In its consultation document From Exclusion to Inclusion, published in 1999, the Disability Rights Task Force points out that ‘inclusion is not only about attendance at a mainstream school. An inclusive curriculum is also essential’. Further, it stressed the need for legislation to overcome widespread discrimination in schools. These recommendations have now been enshrined in the SEN and Disability Act 2001.

This is a time both of challenge and opportunity. On the positive side:

- There are likely to be expectations and duties placed on LEAs and schools to make a greater effort to foster inclusion via clear policies, training initiatives and favourable resource allocations.

- Amendments to section 316 of the 1996 Education Act will strengthen the rights of parents to choose a mainstream school and the SEN and Disability Act 2001 should outlaw discriminatory practices within inclusive placements.

However:

- Recent statistics (Howson 2000) show that the number of children in special schools remains just below 10,000, around 1.3 per cent of the school population. As the author of the report comments, ‘the full integration of pupils into mainstream schools still looks a great distance away’.

- Both the revised Code of Practice and the SEN and Disability Act 2001 have yet to be tested in the courts. Even with the amendment to section 316, LEAs will still be able, quite legally, to deny some individual pupils their right to a mainstream placement.

What research tells us

One of the difficulties experienced over the years by those advocating inclusive education is the continual pressure they face to prove that inclusion works. Yet at no stage has anyone ever been asked to prove the efficacy of special schooling. The assumption has always been that because it is special, with specially trained teachers and a high adult-child ratio, then it must obviously produce better results. Anecdotes abound but do little to clear the air. For each example of an included child who has thrived and benefited enormously from the experience, there is another epitomising mainstream failure, with the child being rescued by a benevolent special school.

Clearly experiments cannot be set up in which a population of children is placed randomly in special and mainstream schools to compare the long-term effects. Neither is it easy to match groups of children in different settings. Factors that influence placement decisions, e.g. social class, parental education...