- 116 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Mathematics for Children with Severe and Profound Learning Difficulties

About this book

The book will covers a wide range of approaches to teaching and learning and demonstrates how mathematics can be related to personal and social development, communication and thinking skills. Written with the non-specialist in mind and including plenty of practical examples, it will make useful reading for teachers in mainstream and special schools, and learning support assistants.

Early years practitioners and teachers in training may find the book useful for its descriptions of how children acquire their foundation of early mathematics and numeracy skills.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Mathematics for Children with Severe and Profound Learning Difficulties by Les Staves in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One

Mathematics in daily life

1 | The significance of mathematics |

In his Royal Institute Christmas Lecture in 1997 professor of mathematics Ian Stewart emphasised, ‘The mathematical mind is rooted in the human visual, tactile and motor systems. Counting is based on touch and movement, geometry is visual’.

In the Goon Show Moriarty asked ‘How are you with Mathematics?’ and Secombe replied, ‘I speak it like a native’. Mathematics is a language we all speak, it is a medium that enables us to observe and share information about our surroundings and occurrences. This book is about how we promote these processes for children who are learning at early stages of development. When regarded as an academic subject, with a leaning towards abstraction and calculation, the relevance of mathematics to such pupils seems marginal. However, mathematics is intrinsically woven into our life and language. In fact the basic concepts of mathematics are so natural to us they are part of the thinking we do even before we speak. The part that mathematical thinking plays in our intuitive reasoning is very important to our conscious functions and appreciation of life. There is a great deal of mathematical learning that takes place before children start school. By that time most children have developed intuitive concepts relating to space and quantity that are the bedrock of their later ability to use the symbolic and abstract aspects of mathematical expression. It is interesting to note that Einstein described his creative mathematical thinking as, ‘Initially involving visual and muscular processes’. He infers that his thinking had sensory roots and said that words and other signs that could be used to try to describe his feelings only came into use after the initial associative play. What better witness could we have to testify that mathematical understanding has physical and sensory origins and mathematical learning is built upon a wider foundation than logic alone?

The fundamental sense of mathematics begins long before we can talk numbers, and there is much to the natural course of learning mathematics before counting; exploring this part of mathematics is very important for children who are at fundamental stages of learning.

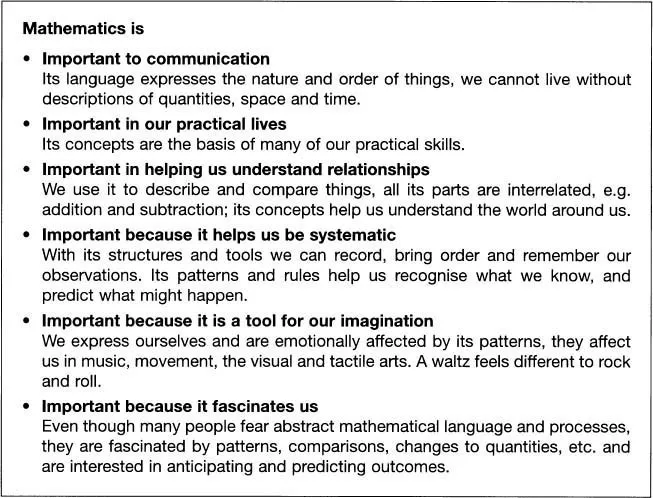

Some people may suggest that subject teaching is inappropriate for children who are at early levels of development, because the nature of early learning is the same in all subjects. But at even the most fundamental levels of learning many activities that children participate in do have distinct associations to specific subjects, they relate to distinctive content, distinct language and ways of thinking. For example, in the process of sharing the experience of reading with an adult, a young child experiences turn taking, visual discrimination, matching symbols to sounds, etc. The same skills would be exercised in the course of playing a dice or number game together, but the two activities have different purposes and flavours. In the reading activity a story emerges, the purpose of the communications, discriminations, and sound matching is to reveal a thread that includes descriptions of circumstances, questions of intent and social interaction. Whereas in the number game as the dice rolls the children use the same skills to be aware of changing quantities, the suspense of comparisons, using number labels, comparisons of size, frequencies. So while the same tools and skills are being used, there is something distinctive about the ways of thinking that are being promoted (Grove and Peacy 1999). On the one hand there is the purpose of literature, and on the other the purpose of mathematics, and these different experiences engender distinctly different ‘Ways of knowing’, it is these distinctly different styles that define the spirits of the subjects (Wragg 1997). So the child is using the same tools and skills in different contexts, and these contexts give the process of learning breadth and real life relevance. When children experience these different purposes and flavours they learn about the existence of different aspects of life, all of which are important to them. Figure 1.1 summarises ways that mathematics contributes to the everyday quality of our lives.

Figure 1.1 Ways in which mathematics is important to our lives

2 | How mathematical learning begins |

The natural and cultural roots of mathematics

Introducing number sense, our natural inclination to notice the numerous – a neurological dimension

Mathematics has been placed upon a pedestal as a realm of abstract intellectual thought. For many years philosophers and psychologists have suggested that mathematical knowledge was the result of the development of logic, and children could not learn it until they were capable of logical thought (Piaget 1965). Recently writers who are interested in the functions of different parts of the brain have paid attention to how mathematical knowledge begins. They have suggested that we are born with areas of the brain that specialise in the recognition of ‘numerosity’, i.e. the perception of quantities. Both Brian Butterworth (1999) and Stanislas Dehaene (1997) have written books that survey the beginnings of mathematical thinking, and the practices of counting, recording and calculation from pre history to modern times. Through these histories and by relating them to the observations and case studies of psychologists and neuro-scientists, they illustrate that at birth we possess a fundamental ‘sense of number’ that enables us to compare and select the larger of two groups. From these early abilities we quickly learn to have a sense of their order by size. Butterworth calls the brain circuitry that provides these processes ‘The Number Module’. He suggests that children use it to develop elementary ideas about quantities and numbers from information they gather through their physical senses and cultural experiences. This is the fundamental beginning of understanding numeracy; without it we would not be able to lead our practical daily lives, nor would mathematics ever fly to its abstract heights.

Models connecting early learning to sensory activity are not new or unique to mathematics. What is fresh and especially interesting for us in Butterworth’s suggestions is the idea of a number module, drawing direct information from touch, sight and sound to extend a sense of number. This is perhaps somewhat akin to the way that we have previously envisaged a sense of colour – we readily accept that children can recognise and match colours before they can name them.

We will return to number sense in a later chapter. It is important for children with very special needs because it relates to learning that is so deep-seated that we take it so much for granted that it has not been part of our curriculum.

Counting – a practical and psychological dimension

As I have mentioned earlier, up to the 1960s psychologists proposed that the development of mathematical knowledge first required the development of logical, abstract thought. Piaget (1965) considered young children’s abilities to learn and recite number sequences and arithmetic facts as simple meaningless acts. More recently research has shown that number concepts and the use of meaningful counting actually interact to enable the child to construct more sophisticated concepts of number, and form the basis of understanding practical and arithmetical operations. There has been increasing interest by psychologists in how children actually learn to count. Though it is an ability that many children master before they attend school, it has been shown to be a complex skill, with many parts. Counting forms the basis of practical mathematics and arithmetic and even the abstract realms of mathematics are dependent upon it. Learning to count is learning to extend the power of your number module. Young children learn it so instinctively that guidance in the National Curriculum only skims over it. Working with children who have difficulties learning to count requires us to know a great deal more about its parts, and, as with number sense, we will return to them after we have considered the background relating to the tools and processes that our children use to learn.

Personal and social mathematics

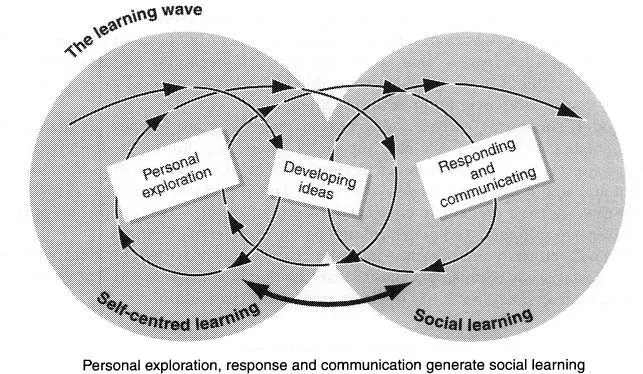

Learning is driven by curiosity. It begins as children explore with their senses. Initially they respond to basic drives to satisfy hunger and other essential needs by reflexive reactions to external sounds and other stimuli, by looking and reaching, etc. Though these processes help them to establish their early relations with other people, they also focus a great deal on exploration that involves absorbing perceptual experiences of a very localised environment. This includes the close examination of their own bodies and hands; though they are not necessarily inclined to share such exploration with others. They realise significant things about their observations and develop ideas which they begin to generalise. They are drawn into communication as they encounter others; they respond, communicating both about the notions they have developed and the questions that their ideas and curiosity raise. The processes of these stages spiral forward like waves, depicted in Figure 2.1 There is repeated feedback and progression as personal exploration results in gaining knowledge and developing ideas that encourage responses and so promote communication. Learning thus progresses from self-centred exploration towards social communication, and then with feedback progresses again; learning rolls on, the process is not always smooth, often like waves it may have its undertow when the preconceptions of old learning hold back the acceptance of new ideas.

Figure 2.1 The learning wave

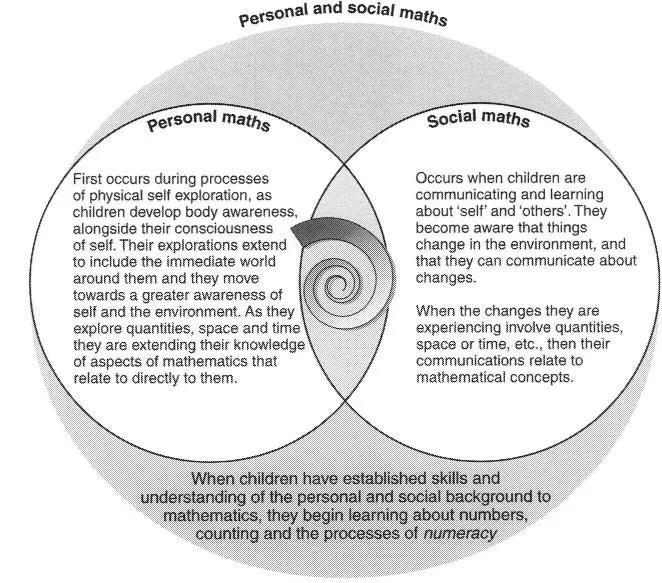

The general process I have described is a commonsense description that may be applied to many aspects of early learning. It involves sensory exploration, sharing what you know with others, comparing their responses and reintegrating new ideas into your understanding – processes described by Piaget as Assimilation and Accommodation. It pertains to mathematical development when the child’s sensory exploration relates to space and time and when it incorporates the use of the number module working with the physical senses to relate to quantities. The interrelations of personal and social activities are depicted in Figure 2.2.

A model like this might suggest to us that our teaching for children at very early stages of development should begin with a focus on personal exploration, using their senses to begin to appreciate and order the world about them – which we might describe as personal maths. As children develop, their own observations encourage them to communicate with others, to share, request and question. We might describe the processes that occur during communication, which relate to understanding and describing quantities, space, time and change, as social maths. Once the children have begun to grasp ideas, which constitute the personal and social background to maths, they begin to realise how to communicate, using those ideas for social and practical purposes. It is then that they are ready to appreciate and learn the beginning skills of numeracy. They do this by extending the innate skills of their number module; first learning to name the small quantities, and describe the order of relationships that previously they have only been able to ‘sense’. Once they have begun, given the development of requisite physical and communication skills, they may move towards the ability to itemise groups, name quantities and numbers, then to count and describe numeric events.

Figure 2.2 Personal and social mathematics

This sequence of learning offers us a structure with which to enhance the early stages of the National Curriculum. Through it we can look in detail to describe activities that encourage biological, cognitive and social experiences that promote the bedrock mathematical understanding. A wealth of ‘personal maths’ occurs in sensory sessions, and ‘social maths’ occurs while communication is being promoted. In the past, mathematical detail within such experiences has not been part of our school curriculum. However, new guidance from the Qualifications and Curriculum Authority, intended to promote access to the National Curriculum for pupils at early stages of development, now recognises the importance of such dimensions of learning.

3 | The strands of early mathematical learning |

It is helpful for us to have an awareness of the natural course of learning, to provide guidance that helps us plan teaching strategies for children who have difficulties that disrupt normal patterns. There are similarities in the skills and processes that children use for gathering and understanding information in different areas of their development, or subjects. Though they are not uniquely ‘mathematical’, they do play roles in helping mathematical abilities evolve. So, through the course of this chapter, we will look at some common strands of early learning and how they intertwine and support mathematical learning.

Introducing the tools and processes and content of early learning

There are a number of strands that are important; they represent physical and mental tools that children use to learn with, and processes in which they use the tools and through which they learn. Each of the strands is composed of a number of threads; none work in isolation. To understand how learning happens it helps if we unravel the braid.

Tools for early learning

One important strand might be described as tools for learning. The tools are skills that develop from the sensory abilities that we are born with. The effectiveness with which we use them may be refined by usage and exercising them is itself part of the process of development. There are a number of threads within this strand, each thread representing a different type of tool. They are:

• sensation, attention and perception;

• sensory motor development;

• communication skills;

• concept development and thinking skills.

The tools of sensation, attention and perception work toge...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part One – Mathematics in daily life

- Part Two – The tools of learning

- Part Three – The processes of learning – phases of cognition

- Part Four – The mathematics curriculum

- References

- Index