eBook - ePub

Industry and Air Power

The Expansion of British Aircraft Production, 1935-1941

- 300 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Industry and Air Power

The Expansion of British Aircraft Production, 1935-1941

About this book

The author begins with a general survey of British aircraft manufacturing in the inter-war period. Policy, production, finance and contracts are examined, and the final chapter is concerned with the mobilization of the aircraft industry in 1939, and the emergency measures of 1940.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Industry and Air Power by Noel Sebastian Ritchie,Sebastian Ritchie in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Military & Maritime History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

British aircraft production between the wars

The British aircraft industry was born in the decade preceding the outbreak of the First World War. Short Brothers and Handley Page were formed in 1908, Blackburn and A.V. Roe in 1910, Sopwith and British and Colonial (which later became Bristol) in 1911. Established armaments manufacturers like Vickers and Armstrong Whitworth also began designing and building aircraft in this period. Although private flying was initially the most important source of demand, the armed services’ growing interest in the military potential of aviation led them to place substantial orders between 1912 and 1914, and at the start of the war the naval wing of the Royal Flying Corps (RFC) had a total of 93 heavier-than-air craft, while the military wing had 179. After this, service requirements resulted in a dramatic expansion of industrial capacity and output. A fivefold increase in employment in the aircraft industry occurred between October 1916 and 1918. Monthly production rose from about ten at the beginning of the war to 2500 in 1918.1

After the armistice, military demand inevitably contracted yet the newly formed RAF continued to provide a market for the vast majority of aircraft produced in Britain in the inter-war years. The equipment and technical development directorates of the Air Ministry’s Department of Supply and Research and the contracts directorate of the Ministry’s secretariat presided over RAF procurement. During the 1920s the Ministry adopted a policy of rationing design contracts between 14 different airframe firms, 11 of which were wholly or predominantly dependent on the Air Ministry for their survival. The intention was to maintain a nucleus of technical and productive capacity which could be expanded in wartime, to improve design through competition, and to prevent contractors from demanding excessive prices for their aircraft.

This chapter examines the consequences of the Air Ministry’s policy. How did it affect the industry’s structural characteristics, its profitability and the volume of its operations? How satisfied was the Air Ministry that a sufficient basis for wartime expansion existed and how did Air Ministry patronage influence the design and production techniques employed by the aircraft industry?

The Aircraft Industry and Aircraft Production, 1918–35

The ‘lean years’

In the history of the British aircraft industry it is usual for the period between the end of the First World War and the beginning of rearmament to be characterised as the ‘lean years’.2 During the war the industry was, of course, extremely profitable. Sopwith, the most famous firm of all, emerged in 1918 with reserves totalling more than £1 million. However, the post-war contraction of demand was accompanied by exceptional financial insecurity. Half of Sopwith’s reserves were given up in excess profits duty and the firm was finally pushed into liquidation following a disastrous effort to diversify its activities.3 Companies like Handley Page, which attempted to join the automobile industry after the war, were likewise hit by the recession of 1920–21. Efforts to promote foreign sales and to launch an air transport service proved equally fruitless, and the losses incurred by Handley Page from these activities totalled £606,000 in 1920.4 Excess Profits Duty forced Martinsyde and the Aircraft Manufacturing Company out of business, and British and Colonial only managed to avoid the duty by transferring its assets to the Bristol Aeroplane Company.5

Many firms from outside the professional industry had been drawn into the aircraft economy during the First World War, but the depressed post-war market for aircraft persuaded the majority to return to their former activities. Some design firms also contemplated completely ceasing aircraft work. The board minutes of Sopwith Aviation record that in October 1919 ‘consideration was given to the advisability of the company totally abandoning aircraft’. However, ‘it was agreed that although the market for aircraft during the next few years was likely to be small, if this company abandoned aircraft now it would be impossible to take it up again in the future. It was therefore resolved to continue designing and experimental work.’ By the time Sopwith went into liquidation in 1920, Hawker Engineering Ltd had already been formed to continue with Sopwith design and manufacture.6

Following the government’s decision, in 1923, to create a 52-squadron home defence force, the aircraft industry moved from what Professor Higham has described as ‘demobilisational instability’ to ‘peacetime equilibrium’, and the Air Ministry adopted its policy of rationing work between different contractors.7 No accurate figures exist for total British aircraft production until the year 1930, when 1456 airframes were built, but Air Ministry orders, which included aircraft ‘exported’ to RAF overseas commands,8 averaged 646 aircraft per year between 1923 and 1930 (see Table 1).

Table 1

British Aircraft Production, 1924–35

Year | Total Air Ministry Orders | RAF Home Commands Orders | Exports | Total UK Production |

A | B | C | D | |

1924 | 563 | – | 188 | – |

1925 | 448 | – | 148 | – |

1926 | 805 | – | 150 | – |

1927 | 392 | – | 140 | – |

1928 | 835 | 495 | 358 | – |

1929 | 615 | 573 | 525 | – |

1930 | 864 | 855 | 317 | 1,456 |

1931 | – | 728 | 304 | – |

1932 | – | 445 | 300 | – |

1933 | – | 633 | 234 | – |

1934 | 652 | – | 298 | 1,108 |

1935 | 893 | – | 453 | 1,807 |

Source: (A) PRO AIR 2/1322; PRO AIR 19/524, 1934–35 figures for deliveries to the Air Ministry; (B) M.M. Postan, British War Production, p. 5; (C) Annual Statements of Trade of the UK; (D) Census of Production (1930 and 1935).

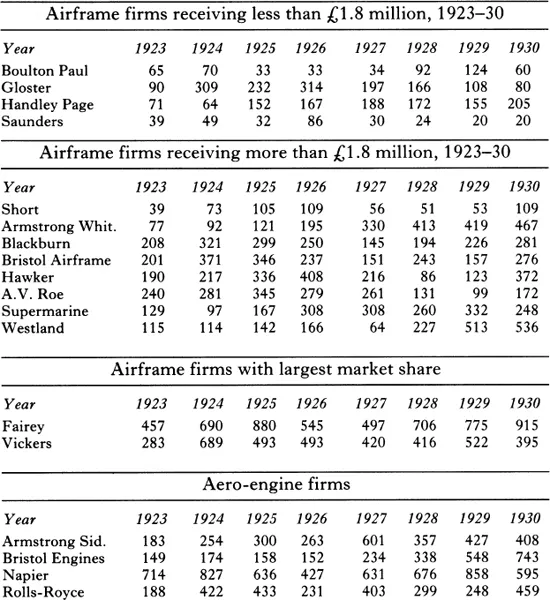

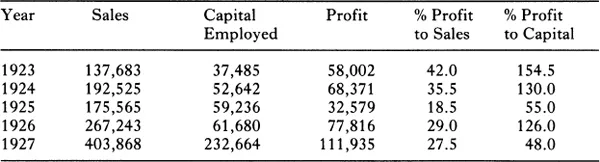

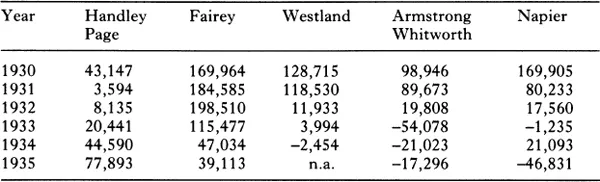

The records show that most of the military airframe companies received at least £1.8 million from the Air Ministry in this period, and the accounts of one such company, Supermarine, demonstrate that it was possible to operate very profitably on the basis of such receipts (see Tables 2 and 3). Nevertheless, financial stability ultimately depended on success in consecutive design contests. Competition was strong because there were so many different contractors, and the chances of failure were correspondingly high. The problem was worsened by the tendency of some firms to rely on the success of their existing designs at the expense of research and development for the future. Hence Fairey Aviation, the most prosperous airframe firm of the 1920s, went public in 1929 with a capital of £500,000 only to see its profits collapse in the early 1930s (see Table 4).

Table 2

Air Ministry Payments (in £000) to Aircraft Firms

Source: PRO AIR 2/1322.

Table 3

Supermarine Profits, Sales and Capital (£), 1923–27

Source: Vickers K757.

Table 4

Net Profits (£) of Five Aircraft Firms

Source: Annual Reports in The Statist; Handley Page archive; HSA, Armstrong Whitworth Accounts.

The financial status of the industry as a whole improved after 1923, but Air Ministry payments to five contractors were substantially lower than the average. One such firm was Handley Page, whose Air Ministry receipts grew steadily throughout the period. Another was Gloster, who was paid £314,000 in 1926 and just £80,000 in 1930. But the receipts of Short Brothers, Saunders, and Boulton Paul were lower still. These firms obtained little or no encouragement from the Air Ministry and only survived by diversifying their activities and using the income from non-aviation business to finance aircraft design and experimental work.9 Between 1920 and 1930 Short built only 36 aircraft;10 Saunders’ average annual receipts from the Air Ministry amounted to just £37,250 between 1923 and 1930; and although Boulton Paul employed several thousand workers in 1925, only 150 were engaged in aircraft manufacture.11 It is difficult to see such companies as serious contenders for the military market yet as long as they continued to undertake experimental work they could capitalise on any revival of air force demand whereas, as the Sopwith minutes suggest, abandoning any aircraft manufacturing meant abandoning aircraft manufacturing altogether.12

The financial problems facing these firms were exacerbated by the transition from wood to metal construction which occurred in the later 1920s. The new construction methods involved an increased commitment to development and testing, the acquisition of new machinery, and changes in manufacturing processes, each of which required considerable expenditure. Saunders was taken over in 1927 and made losses in the ensuing five years.13 Even more affluent concerns like Blackburn were forced to seek external financial assistance ‘as no shareholders had offered to find additional capital during a critical period’. In consequence the chairman, Robert Blackburn, lost his controlling rights on the board of directors, although he regained them in December 1931 after an upturn in the demand for the company’s aircraft.14

The aggregate domestic demand for aircraft remained relatively stable until the beginning of rearmament but production contracts were less evenly rationed during the early 1930s than in the previous decade.15 The export market also contracted. The number of aircraft exported fell from 525 in 1929 to 234 in 1933.16 Moreover, firms became embroiled in another technical revolution: the replacement of the biplane by the monoplane. A memorandum from the industry’s trade organisation, the Society of British Aircraft Constructors (SBAC), noted that ‘since the transposition from wood and metal machines to all metal machines, and since the development of the art has required greater refinement and form, the cost o...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication

- Table of Contents

- List of tables and figures

- Editor’s Foreword

- Acknowledgements

- Abbreviations

- Introduction

- 1. British aircraft production between the wars

- 2. The Air Ministry and military aircraft production, 1935–39

- 3. The airframe industry and military aircraft production, 1935–39

- 4. Aero-engine production, 1935–39

- 5. Manpower for the aircraft industry, 1935–41

- 6. Finance, contracts and prices in the aircraft industry, I935–41

- 7. British aircraft production, 1939–41

- Conclusions

- Bibliography

- Index of aircraft and aero-engines

- General Index