![]()

1 Setting the scene for strategic stakeholder engagement

Summary

This chapter provides a context for the book and begins by relating developments that led to the demise of British Energy, the UK’s largest electricity generation company in 2002. What is clear with hindsight is that a lack of an effective stakeholder engagement programme was a major contributing factor in its spectacular failure in the market. The lessons learned from the financial collapse of the company and its subsequent rehabilitation show what can be achieved with the right approach to stakeholder engagement. This chapter also contains the views of experts in this area, their comments helping to inform what needs to be addressed for a successful engagement programme; their views confirm that this book is essential reading for practitioners in this area, in organisations across the economy, in the UK and in many other countries around the world.

1.1 An influential case study

In 2002, the Board of British Energy Group went to the Government seeking financial support to carry on operating. This was an unusual request from a private company but this was no ordinary company; it was the operator of the UK’s eight most modern nuclear power stations, producing around 25% of the UK’s electricity supplies and deemed essential for the economic well-being of the country. The Government provided an emergency loan facility to allow the company to continue operating. In the following weeks and months, the Government was confirmed as the single biggest shareholder of the company, and a long rehabilitation process began under a new Board and management.

Fast-forward to 2009 and British Energy was sold to EDF Energy for £12.5 billion. In the intervening period, the company’s charismatic CEO Bill Coley and a small expert Executive Team, supported by an excellent Chairman in Sir Adrian Montague and his Board, led the company back into financial health and managed to improve operational performance, solving some major engineering problems in the process. The Government received a total of £6.7 billion through two sales of shares, with the money going to the Nuclear Liabilities Fund to help meet the long-term liabilities associated with the decommissioning of the plants and treatment of the waste streams.

Fast-forward again to 2016, and the Government confirmed the contracts awarded to EDF Energy and its financial partner China General Nuclear (CGN) under new market arrangements that would facilitate the building of nuclear reactors at Hinkley Point C and Sizewell C.

This outcome has significant implications for the UK’s nuclear industry. A country that gave the world its first civil nuclear power station at Calder Hall in 1956, and then built, operated and life-extended 15GW of Magnox, AGR and PWR technologies over the next 60 years would now rely heavily on foreign investment and technology to fund and build the next generation of nuclear power stations.

1.1.1 Poor decision-making in a changing market

The UK has been very successful in encouraging significant inward investment into the electricity sector, as it has in other parts of the economy. But it is also fair to say that there may also have been a missed opportunity for the UK to remain a leader in the nuclear power sector with all the wider long-term benefits that would bring, for example, to the industrial base of the country.

There was, then, an alternative world out there for British Energy, one in which it was a national champion in the UK’s nuclear renaissance, using its bedrock of expertise, sites and relationships with the regulator and supply chain. But a number of important developments in the years following its privatisation in 1996 were ultimately not helpful to the company:

- A highly competitive market brought about by the Government’s New Electricity Trading Arrangements (NETA), which served to drive wholesale prices below the cost of generating a kilowatt-hour of electricity in nuclear power stations.

- The forays by British Energy into the US and Canada, which were undoubtedly successful ventures when viewed from the monies raised once they were sold under fire-sale conditions, but which may have diverted resources, both monetary and human, away from the core business in the UK operations.

- The failure by British Energy to compete with EDF Energy to buy London Electricity, a company that had more than two million customers in the London area and a gas distribution business. This would have been a strategic acquisition that would have allowed British Energy to realise value from the domestic retail sector as prices declined in the wholesale market.

- A significant overpayment for Eggborough coal-fired power station by the company, which allowed greater trading flexibility, but was subsequently written down in value. The plant did prove its worth in later years because its flexible power generation complemented the relatively inflexible generation from the nuclear stations.

- The dividend policy that gave significant benefit to shareholders at a time when the money could have been used to maintain the company through difficult market conditions.

- The original, inflexible, arrangements under which British Energy was privatised, and the costs associated with the fuel contracts with British Nuclear Fuels Ltd (BNFL) and other liabilities, which did not reflect changing market conditions.

- The failure of negotiations with BNFL, a publicly owned company, on a new cost structure for the fuel contracts, one that linked price of fuel to the electricity price in the wholesale market. Had the negotiations been successful, this would have provided financial relief for the company at a time when it was under considerable cost pressure in a difficult market.

- The Board’s overreliance on a single study by consultants that wrongly projected that wholesale prices would remain low for a considerable period. This undoubtedly influenced the Board’s decision to seek support from the Government when it had a major loan facility to draw on to maintain operations until the market improved.

It is not possible to say that one of these had an overriding effect on the demise of British Energy, although the low wholesale prices brought about by the introduction of NETA certainly put enormous financial pressure on the company; rather, it was likely to have been a combination of these factors. But whatever the truth, hindsight suggests the problems were exacerbated because of the company’s inadequate engagement and lack of influence with decision-makers in the policy development arena during the period between privatisation in 1996 and the call on support from Government in 2002.

1.1.2 Missed opportunities by British Energy and the Government

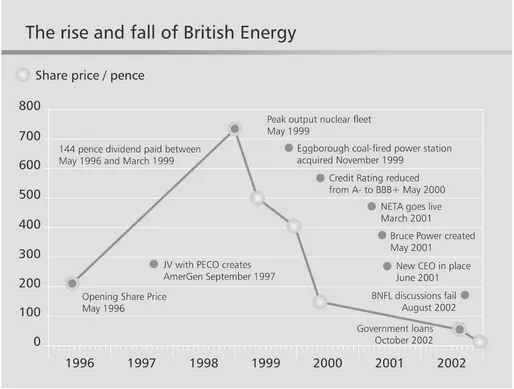

The New Electricity Trading Arrangements (NETA) were introduced in early 2001, raising competition to new levels and leading to lower electricity prices to the benefit of domestic and industrial consumers, at least in the short to medium term. The potential impact of NETA on nuclear must have been understood, particularly by those who had constructed the market framework: the officials and the regulator. That there was no concern about the pressure on 25% of the UK’s electricity supplies is surprising, but perhaps they were complacent because of British Energy’s spectacular share price, which climbed from an opening price of 203 pence on privatisation in May 1996 to 733 pence three years later, at about the time the new trading arrangements were being developed.

It is interesting to note that the Government would later say that it could not intervene in the market for the benefit of a single company because of the need to ensure fair competition in the electricity market, even though imposing NETA on an existing market naturally favoured some technologies over others and some companies over others.

NETA, then, had some severe ramifications for British Energy. An active engagement programme with key decision-makers in Government, at an early stage, in which the longer-term implications of the new market arrangements for the company were highlighted, might have brought a more sympathetic hearing

Illustration 1.1 The rise and fall of British Energy

The price of British Energy shares, and the associated influential events, summarise the rapid rise and fall of what was the UK's largest independent generator.

Notes: JV, Joint Venture; PECO, Philadelphia Electric Company; NETA, New Electricity Trading Arrangements; BNFL, British Nuclear Fuels Limited.

when the next policy developments were being considered: the Climate Change Levy (CCL) and the Renewable Obligation (RO). There were opportunities to influence these policy developments, to improve the competitiveness of nuclear generation in the market through the CCL and to limit the cost to the business of the RO; success in one or the other, or both, initiatives would have had a beneficial impact on the finances of the company.

Climate Change Levy

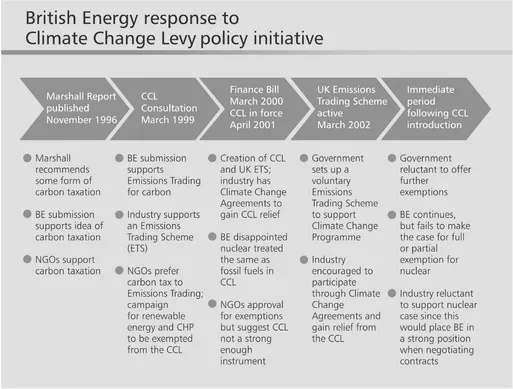

The Marshall Report in 1996 suggested that some form of carbon taxation was an appropriate response to the challenge of climate change, with the options being carbon taxation or a market-based carbon trading scheme. This led to the creation of the CCL to encourage energy efficiency, and through this a reduction in carbon emissions within UK business.

The CCL was a tax on the business use of energy. It was the first policy initiative to address carbon emissions and came into force on 1 April 2001 following extensive consultation. It was designed to be broadly revenue-neutral with some of the revenue used to cut employer national insurance contribution (although these were subsequently increased again a short time later), and to promote the development and deployment of low-carbon technologies.

Following an active lobbying campaign by several stakeholders, most notably non-governmental organisations (NGOs), electricity from renewables and Combined Heat and Power (CHP) was made exempt from the CCL and awarded Levy Exemption Certificates (LECs) for each MWh generated; LECs could then be sold to suppliers who used them to prove that they had supplied non-domestic customers with renewable electricity. However, beyond these exemptions no distinction was made between carbon (i.e., fossil) and low-carbon (i.e., nuclear and hydro) sources of electricity, with both being subject to the CCL.

British Energy operations made, arguably, the largest contribution to carbon reduction in the UK, with almost 50 million tonnes avoided each year at that time, when compared to the prevailing fossil fuel mix. The UK Government in its various climate change consultation documents acknowledged the contribution that nuclear power made, and would continue to make, in mitigating carbon emissions. The company believed there should be financial recognition for this low-carbon nuclear electricity. It felt the Government could do this by:

- Total exemption of nuclear generation from the CCL, which would make it more competitive in the wholesale market.

- Partial exemption of nuclear from the levy (i.e., the levy could be less than the original cost of 0.43 pence/kWh).

- Exemption for electricity generated from projects beyond business-as-usual, for example, those improving the output of the stations or those leading to life extension of the stations both of which would benefit the UK’s climate change efforts and maintain security of supply in the longer term.

A full or partial exemption of British Energy’s output in 2000 could have allowed the company to keep operating through the wholesale price nadir until the market recovered to more sustainable levels, as it subsequently did; it would also have recognised the important contribution nuclear generation was making to the UK’s decarbonisation agenda.

British Energy’s nuclear generators are responsible for 20 per cent of total electricity generation and it plays a part in contributing to the reduction of CO2 emissions.

Patricia Hewitt MP, former Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, Hansards, House of Commons debate, 28 November 2002

The Government claim that the Climate Change Levy forms part of their strategy to meet our climate change commitments. As nuclear power is the main energy source that does not produce carbon dioxide emissions, the Government’s policy is an absurd contradiction.

Tim Yeo MP, former Shadow Secretary of State for Trade and Industry, Hansards, House of Commons debate, 28 November 2002

In its submissions to Government, British Energy supported carbon taxation but favoured a market-based emissions trading scheme to deliver a cost for carbon on fossil generation responsible for carbon emissions. In the event, Government came forward with both the CCL and a very limited voluntary UK Emissions Trading Scheme, neither of which helped low-carbon nuclear generation. The organisation’s engagement programme was limited, focusing almost entirely on a few officials in Whitehall and on briefing the odd supporter of nuclear in the House of Lords. The issue was raised with officials several times by different company executives, but the Government was reluctant to offer more exemptions so early in the lifetime of the CCL, and particularly to an unpopular nuclear sector.

As a result, the engagement initiative failed. Even when the financial pressures on British Energy were threatening the very survival of the company, the response from officials in Whitehall was muted at best, and no CCL exemption for nuclear generation was forthcoming. The real damage was caused because of poor engagement much earlier in the process, at the time of the formulation of the CCL. Renewables and the CHP sector were given exemption from the CCL, and this was achieved by having a good narrative, strong support, and a highly effective lobbying strategy; in contrast, the nuclear operators, despite having strong arguments, failed.

In an interesting postscript, exemption of nuclear (and large-scale hydro) would essentially have converted the CCL to a carbon tax. Ten years later, and in the wake of a very low market price for carbon in the EU Emission Trading Scheme, the CCL was modified to accommodate a Carbon Price Floor; the latter was

Illustration 1.2 British Energy response to Climate Change Levy policy initiative

Carbon pricing should have been a significant financial benefit to carbon-free nuclear generation in the UK; in the event, the Climate Change ...