1

How Is This Book about Jewish Humor Different from All Other Books about Jewish Humor?

If you aren’t Jewish, the title of this chapter won’t mean very much to you, except that it might seem rather long and convoluted, with claims to uniqueness of dubious validity. If you are Jewish, or if you know anything about Jewish holidays, you’ll recognize this as a parody of the famous “question” that children are asked to answer during the Passover Seder.

The Passover Seder

In this combination religious observance and feast, the youngest child is asked a question and, in turn, asks four questions:

How is this night different from all other nights?

On all other nights we eat either leavened bread or unleavened bread (matzos); on this night why only unleavened bread?

On all other nights we eat herbs of any kinds; on this night, why only bitter herbs?

On all other nights we do not dip our herbs even once; on this night, why do we dip them twice?

On all other nights we eat our meals in any manner; on this night why do we sit around the table together in a reclining position?

The Seder, which means order, tells the story of the escape of the ancient Jews from the Pharaoh in Egypt and offers contemporary Jews an opportunity to relive the experience existentially. Jews all over the world read the Passover Haggadah—a guidebook that tells them how to conduct the Seder service. The Passover Seder is, in essence, the answer to these questions. During the Seder, a goodly amount of wine is consumed and, at the end, funny songs are sung, so we have the combination of sadness and happiness, a bittersweet quality that some have found in much Jewish humor.

Let me point out, also, that this is one of the earliest examples of another trait which is supposedly common to Jews—answering a question with a question. In this case, four questions.

How is this Book Different?

This book is, like the Passover Seder, an answer to the question I posed in the title of the chapter. My focus, you will see, is not only on the subjects dealt with in Jewish humor but also with the techniques found most commonly in Jewish humor and, in particular, in certain Jewish jokes that I happen to like very much and which I think are representative and significant.

But before I start analyzing Jewish humor, I would like to say something about humor in general.

Why do we Laugh? How do you Explain Humor?

These questions have, as I pointed out in my preface, perplexed philosophers and deep thinkers for centuries. Why anyone laughs is a mystery. Aristotle is supposed to have written a book on humor that has been, most regrettably, lost. Many of the greatest philosophers, such as Hobbes, Kant, and Bergson, tried to explain why we laugh, and the same holds true for psychologists, psychiatrists, linguists, political scientists, sociologists, and so on.

There are probably hundreds of theories of humor, and one book I own, Ralph Piddington’s The Psychology of Laughter: A Study in Social Adaptation, lists dozens of theories elaborated by thinkers such as Locke, Rousseau, Descartes, Hegel, Schopenhauer, Spencer, Darwin, and Freud. (Freud’s book, Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, has a number of excellent Jewish jokes in it.)

Generally speaking, there are four dominant theories of humor, and all the other theories fall under them. The first theory argues that humor is based on some kind of incongruity—that is, what we get is not what we expect; the second theory argues that humor is based on a sense of superiority (in the person laughing); the third theory, Freud’s psychoanalytic theory, suggests that humor involves masked aggression (and is also connected to various economies in psychic expenditure). The fourth theory, which I would describe as a cognitive theory, ties humor to the way the mind processes information and the creation of play frames that indicate that what is being recounted is not to be taken seriously.

What Makes us Laugh? A Different Approach

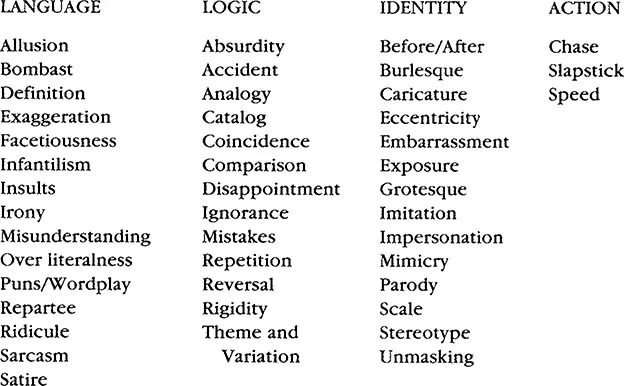

Figure 1.1 Categories and Techniques of Humor

I have elaborated, in a number of articles and books, a different approach to humor—one that doesn’t ask why we laugh (we probably will never find out) but asks what makes us laugh. I made a content analysis of all the humor I had in my house a number of years ago—of comic books, books of jokes, books of Jewish folklore, plays by every one from Shakespeare to Ionesco, books of humorous verse, short stories, novellas, and novels, and so on—and came up with what I suggest are the forty-five techniques of humor that all humorists use, in various permutations and combinations.

I will be using these techniques to analyze a number of Jewish jokes, to see what they reveal about how these jokes generate humor and what they reflect about Jews and Jewish culture. I should point out that some scholars do not like this typology (one scholar called my typology “inelegant”) and argue that I confuse categories in it. My answer is that it is reasonable to consider styles such as parody and satire as techniques; one parodizes and one writes satirically. It may be that some of my categories, such as burlesque, are too broad, but for all practical purposes what I have elaborated in my list of techniques enables us to understand how humorists generate laughter better than any other method I am familiar with.

We know, I would say, what makes people, in general, laugh. And we can find out how humorists, in all media, working in all genres, create humor (even if they can’t explain things themselves). But is there anything unusual about what makes Jews laugh? Why should Jews, a “despised people,” as some have put it, have such a remarkable sense of humor?

An Aside on Three Aspects of Humor

One of the basic techniques of humor, as the figure above shows, is disappointment and defeated expectations. A subcategory of that is going off on tangents in shaggy-dog jokes and interrupting what seems to be the logical order of things. As a humorist, as well as a scholar of humor, I claim the right to go off on tangents from time to time.

There are, let me suggest, three ways to look at humor and its rewards. These are found in the chart below:

Haha | Laughter and Pleasure |

Ahah | Discovery and Pleasure |

Ah | Triumph and Pleasure |

“Haha” represents an involuntary (though desired) response we make to jokes and other forms of humor that generate sudden laughter. “Ahah,” on the other hand, suggests a kind of discovery through humor of some important insight. “Ahah” is an inversion of “Haha,” and the focus is not on a sudden burst of laughter (which may be connected to insult and aggression, for example) but on an epiphany, a sudden discovery of some relationship between things we had not seen before. “Ah” represents a sense of relaxation, of well-being, of success, perhaps even a sense of triumph in some respect.

All three may be found in the same joke or “text” (to use the jargon of contemporary literary theory). When you find all three in a joke, you have, I would suggest, a very fine joke. Not only a fine joke, but a profound joke. Not only a profound joke, but probably a very profound joke. Consider the following joke, which is repeated in most books of Jewish humor:

You’re Right!

A man comes to a rabbi’s house and asks the reb-betzin, “Can I see the rebbe? It’s most urgent.” The rebbetzin shows the man in to see the rabbi. The man then recites a litany of complaints about his wife. As the man speaks, the rabbi nods his head in agreement. “Yes, yes... you’re absolutely right. “This gives the man great comfort, and he leaves. A short while later, the man’s wife comes in and demands to see the rabbi. She is in a state of great excitement. So the rebbetzin shows the woman in. ”I’m here about my husband, “she tells the rabbi. Then she lists a number of complaints about her husband. As she talks, the rabbi nods his head and says” Yes, yes ... you’re right.” The woman calms down, thanks the rabbi, and leaves. Then the rebbetzin comes in and says to her husband, “I don’t understand you. When the man came, you agreed with everything he said. Then his wife came and contradicted everything the man said, and you agreed with her. You’re on both sides of the same argument.” The rabbi nodded his head and said “Yes, yes. .. you’re right.”

In this joke, it is true that the rabbi agreed with two people who had diametrically opposite views, and his wife saw this and called him on it. What she didn’t recognize, it is suggested, is that the rabbi’s main concern was in calming each of the excited partners down and giving them some comfort. This joke has all three of the general kinds of humor in it: laughter, discovery, and success (triumph over adversity). It also shows that human qualities are more important, in many cases, than logic or legalism.

What, or is it Who, Are the Jews?

The Jewish answer to this question is, “Why do you want to know?” But logic tells us that we should come to some conclusions about who and what Jews are, in order to understand Jewish jokes and humor. Deciding who is and who isn’t Jewish, or who isn’t really Jewish, is not an easy matter, by any means.

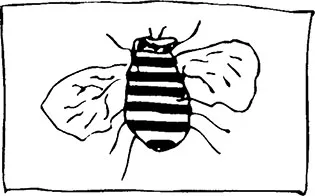

Two Bees

Two bees, Mike and Melvin, are flying through the air. One of them, Melvin, is wearing a Yarmulkah. “Why are you wearing a Yarmulkah?” asks Mike. “I don’t want to be mistaken for a WASP,” replies Melvin.

First of all, we have to recognize that Jews are people who practice, with varying degrees of following the rules, Judaism, the Jewish religion. Technically speaking, according to the Jewish religion, any person born to a Jewish mother is Jewish. (People who are not born to a Jewish mother but convert are also Jewish, though Orthodox Jews don’t consider conversions by Reform Rabbis and maybe even Conservative Rabbis to be valid.)

I would suggest that if people don’t identify themselves as Jewish and don’t practice Judaism, whether they are the children of a Jewish mother or not, they are not Jewish. It helps if, in addition to identifying oneself as Jewish, one practices Judaism (even if only to a minor extent) and one is raised in what might be described as Jewish culture. This involves such things as religious practices, dietary observances, instruction in Jewish beliefs, and so on.

Let me offer an example that involves religious practices. To make sense of this joke, it is important to know that Orthodox Jews have a rule that says men and women are not allowed to dance together. At weddings, the men dance with other men and the women dance with women. Let me add that Conservative Jews and Reform Jews do not have this rule.

No Dancing Allowed

A young Orthodox Jew is getting married and he asks his rabbi, “Could you possibly allow me to dance with my wife after we’re married?” “No,” says the rabbi. “Thats forbidden.” So the young man asks the rabbi a question about having sex. “Would it be okay for us to have sex on the rug?” “Perfectly fine,” says the rabbi. “What about having sex on a sofa?” “That too is fine,” says the rabbi. “And while sitting on a chair?” “Yes, if you like to do it that way,” says the rabbi. “What about having sex while standing?” “No, no!” says the rabbi. “Thenyou’d end up dancing together.”

This joke is obviously a Jewish joke—it involves Jews, rabbis, and Orthodox Jewish religious practices. Not all Jewish jokes have to be so obviously Jewish, but there has to be something Jewish about the events in the joke and the people involved in the joke for a joke to be a Jewish joke.

Second, I would say that Jews are often described as a “people,” a group of people who have something in common. Jews descend from the ancient Hebrews and thus have a unique ancestry. Jews are not a racial group— there are Jews in many different races. But Jews all have a religion in common and, despite considerable differences, some common cultural attributes generally tied to their religion and various customs, practices, and dietary prescriptions that are connected to it. Jews are sometimes called “people of the book,” the book being the Torah, the first five books of the Old Testament.

Third, Jews are commonly understood to be an ethnic group—a rather loose term used to describe people who belong to some religious, racial, cultural, or national group. The term ethnic is derived from the...