- 340 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Coercion

About this book

Coercion, it seems, like poverty and prejudice, has always been with us. Political thinkers and philosophers have been arguing its more direct and personal consequences for centuries. Today, at a point in history marked by dramatic changes and challenges to the existing military, political, and social order, coercion is more at the forefront of political activity than ever before. While the modern state has no doubt freed man from some of the forms of coercion by which he has traditionally been plagued, we hear now from all sectors of society complaints about systematic coerciveness-not only on the national and international levels, but on the individual level as well.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1 Coercion: an Overview

J. Roland Pennock

“Coercion signifies, in general, the imposition of external regulation and control upon persons, by threat or use of force and power.” So says the Dictionary of the Social Sciences. As the reader will discover for himself, this definition does not meet with universal acceptance. In particular, the distaff member of our team takes issue, arguing that more subtle forms of influence than force and power may qualify. By any definition, however, “coercion” invites contrast with “liberty” or “freedom,” as in the title of Bernard Gert’s chapter. Is one the obverse of the other? Indeed, it might even be suggested that in discussing one of these concepts much or all of what it would be appropriate to say about the other has already been covered.

Ten years ago the annual volume of NOMOS was devoted to “Liberty.” Perhaps no great significance attaches to the differences in their tables of contents. Different editors and changed times may largely account for the differences in subjects discussed. Moreover, on that earlier occasion, the Society, at its annual meeting, had been marking the centennial of the publication of “On Liberty.” Half of the chapters and slightly over half of the pages were devoted in whole or in part to John Stuart Mill Even without the occasion for celebration, this distribution would have seemed only mildly disproportionate in a volume devoted to this topic.

“Coercion,” however, has no patron saint. No name stands out as demanding discussion in the present volume. Defenders of “authority” are numerous; and the name of Hobbes, in this connection, eclipses even that of Mill. Yet authority is by no means the same as coercion. Moreover, although Hobbes is no great defender of liberty, authority is not for him its opposite. Rather liberty’s opposite, according to Hobbes, is that which hinders a man from doing what he has the strength, wit, and will to do. And if this is not the definition of coercion (as it would appear to be if we were to accept the Dietionary of the Social Sciences definition), it at least includes coercion.

“Liberty” is a “virtue word“: for some more than for others, but it generally has a positive connotation; coercion, the reverse. It may contribute to understanding to compare the two terms more carefully, not directly in terms of their definitions (as is done in the four immediately succeeding chapters) but in terms of the problems, similar and dissimilar, to which consideration of their meanings gives rise.

I

Let us begin with a series of situations in which the definitional problems seem to be similar, if not identical, supporting the idea that the two terms are logically related by opposition. Take the case of physical laws, gravity, for example. We do not normally say that a person who accidentally steps off a cliff is coerced into falling to the base below, nor that he is thereby deprived of freedom. Peripheral usages may be found. We might say that the invention of the airplane freed man from being confined to the surface of the earth. We would hardly say that, previously, he had been coerced to remain on the earth’s surface. Possibly the difference arises out of the fact that in the case of liberty we have our attention mainly on what is liberated (since the word refers to the condition of the being that is freed) and hence are less likely to notice that the liberating factor is of a kind (a physical law) not usually thought of as affecting liberty. The concept of coercion, on the other hand, directs attention to the source of the coercion (since it refers to the use of force rather than to its effect), and hence to the fact that the human element, usually associated with coercion, is here lacking. (Bayles maintains that coercion is necessarily an interpersonal relation.)

Now let us shift to the case of coercion that is human but not deliberate (at least as far as concerns its coercive effect). We may speak sometimes of being forced to do something by “the logic of the situation.” Take the case of “cutthroat” competition. The competitor who cuts his prices down to the level of his direct costs is not trying to coerce others to do the same. In fact he would much prefer that they did not. But they are likely to do so. And they will feel coerced.1 And the coerced party will also feel that his liberty has been curtailed.

Yet these are borderline cases. Suppose we shift the situation to a busy street intersection, or, rather, to one where the traffic is virtually constant on one of the streets but only sporadic on the other. The traffic light has ceased to function, with the consequence that the people on the cross street find it virtually impossible to get where they want to go. Are they being coerced? One would hesitate to say so. Is their liberty being curtailed? I think one would hesitate to use this terminology, as well; although perhaps it would be a trifle less forced than to say they were being coerced. If there is a difference here, it probably goes back to the point made above about the ways in which attention is directed by the two words. It is more difficult to think of the drivers of the cars on the main road exercising coercion in this situation than it is to think of the others as being deprived of liberty, for the latter are indeed frustrated. Again we seem to be operating at the borderline of the commonly understood meanings of both terms. Perhaps the distinction I sense is between the price-cutter, who is departing from his previous behavior pattern and who is aware of the effect of his action on his competitor–even though he does not intend it–and the driver, who does not change his behavior and may not even know that the light is out of order.

Take a case of social necessity the results of which are favorable to me. Being brought up in an English-speaking community, I am (in one sense) compelled to learn the English language. This is perhaps no less a matter of the “logic of the situation” than the cases discussed above. Yet one would hesitate to say either that I was coerced or that I was deprived of liberty. The two cases seem to be on a par in this respect; and the crucial difference from the preceding cases is that here there is no question of going contrary to my wishes. Furthermore, I am actually more free, or at least I have more options than would otherwise have been the case. What I am in a sense required to do is essential to the fulfillment of my needs and desires.

Similarly, the structure of the situation may produce the effect in question in more subtle ways. Take the case of an Amish commanity located in the midst of a society growing ever more unlike it in ways of which the Amish disapprove. Are they coerced? Are they unfree? (I exclude cases of legal compulsion.) How we would answer these questions may be in some doubt, but I believe the answer, whatever it was, would be the same in each case.2 More generally, it is the prevailing ideology that is at issue and that suggests that one of our terms is the counterpart of the other.

May one be coerced by disapproval, say by the disapproval of society? And if so is one’s liberty limited? It would seem that an affirmative answer is called for in each case. Mill of course was greatly concerned about the pressure of society toward conformity. One can certainly imagine cases where the pressure to conform was stifling to liberty. And in such cases I suspect one would say that society was exercising coercion, even though it was not deliberate. But note, if the price of nonconformity is not great, we may hesitate to say that liberty is curtailed. Under these circumstances, we may say that people who conform against their preferences or convictions are either fools or weaklings. They are perfectly free to do as they please, we might say. Moreover, no one is coercing them. Here, if there is any difference, we might be a little more inclined, in my opinion, to say they were being coerced than that they were not free. (This conclusion accords with Gert’s definition of coercion “in the wide sense.“)

In general, the question raised by this situation relates to both liberty and coercion: it is whether all restraints and constraints are to be counted as constituting coercion or limiting liberty, or whether only restraints of a certain kind and degree count as being coercive and as interfering with liberty. (The case of an unsuccessful threat, implicit here, will be discussed below.) While for the most part the question of degree seems to affect our usage of the two terms in like fashion, I believe one can note divergences in two directions. In the case just considered we may be more inclined to qualify our judgments about liberty by reference to some standard of reasonableness than we are in the case of coercion, although in at least one kind of situation Virginia Held would not agree. (Again the emphasis is on the human object of action and hence upon subjective factors–here “reasonableness.“) To shift once more to traffic controls –but here a properly functioning rather than a malfunctioning light–we might be more ready to say that a red light is coercive than that it deprives of liberty. If so, I would suggest that the reason for this asymmetry of usage is because, in the case of liberty, we are more apt to judge the particular situation in terms of the whole systern of which it is a part. Thus we might not consider a red light as depriving us of liberty because we realize that on the whole it makes for less frustration than would otherwise be the case. In the case of coercion, where the emphasis is on the act rather than the condition, the broader context is less relevant.

Finally–and this is the question on which Bayles, Gert, and Wertheimer are aligned against Held and Mcintosh–must the incentive, the sanction, be negative? The first three authors mentioned contend that it must: a promise of benefit is never coercive, they maintain. Held and Mcintosh argue on the other hand that this is not the proper test. Rather, the question is whether the incentive (or disincentive) is one that a normal person might reasonably be expected to resist. The point to be made here is that precisely the same issue arises with respect to liberty. Most writers probably would argue that a bribe does not interfere with liberty, but Stanley Benn takes the opposite point of view.3

II

Thus far we have reviewed a series of problems that one encounters in defining coercion and we have found that the same problems usually arise in defining freedom. Generally, they tend to support the picture of coercion and freedom as opposite sides of the same coin, although even here we have noted certain qualifications. Now we turn to a set of problems that seem to bring out differences rather than similarities between the two concepts. First, two general points. Coercion is what someone does. It is an exercise of power. Freedom, on the other hand, is a condition.4 The two terms are not parallel. But this does not mean that they cannot be counterparts. The condition might always result from coercion or its lack. Liberty might always be describable in terms of the presence of coercion; and coercion might be definable in terms of its effect on liberty. The second general point arises from the fact that coercion is a form of the exercise of power. As is well known, the relation between liberty and power is ambiguous, or at least debatable. It should not be surprising, therefore, that this ambiguity shows up in some of the cases to be discussed below.

Even if coercion always interferes with liberty–at least with a specific liberty–does its absence always result in liberty? In other words, is coercion the only thing that interferes with liberty?4 Not if we accept the notion of “pyschological freedom.” According to this concept any psychological state that interferes with harmony between basic motives and overt behavior is an interference with liberty. Bernard Gert argues, however, (Chapter 3) that this concept of liberty is too broad–that it comes from collapsing the distinction between “liberty” and “power.” Moreover, it should be noted that Bay himself, for whom liberty is certainly the supreme good, declares that coercion is “the supreme political evil.”6 So perhaps the difference just noted between coercion and the opposite of liberty is not so great after all. In fact, it may disappear entirely if we limit the discussion to “political” liberty or even to the broader concept of “social freedom.”

Another somewhat puzzling case is that of “manipulation,” meaning by that term conditioning or otherwise influencing behavior by controlling the content and supply of information. Here again something other than coercion may affect a person’s freedom in the very broadest sense of that term. This is what Bay calls “potential freedom.” Again the difference between coercion and freedom’s opposite appears only where “freedom” is used in an extended sense. It once more appears, however, that the words “liberty” and “freedom” have a certain elasticity, a certain tendency to be stretched beyond their usual meanings that is less true of “coercion.”

This same tendency is noticeable in connection with the idea of being “forced to be free.” Rousseau’s famous, or notorious, concept clearly could not be identified with the absence of coercion, since it itself involves coercion. Nor can freedom coerce. Again we are made aware of the fact that “freedom” is often used less precisely than “coercion.” Even Rousseau, when he spoke of being forced to be free, would probably have admitted that any forcing, any coercion, entailed some limitation of freedom or limitation of some freedom, even though freedom in the large might be increased. One is reminded of Green’s concept of “hindering hindrances,” which clearly involves coercion and the limitation of someone’s liberty in behalf of a greater or more important liberty. Although most would agree with Bay that coercion is evil, other things being equal, the evaluative connotations do not seem to have rubbed off onto the word itself to the same extent that the positive connotations of freedom have.7 Thus some may say (perhaps rather carelessly) that “bad” liberty is not really liberty (possibly, it is “license“), but the parallel statement that “good” coercion is not really coercion, or even that it does not “really” interfere with liberty, does not occur.

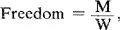

Perhaps most people would agree that both of the terms under discussion admit of degree. However, in one respect Michael Bayles, in his chapter below, does not agree. (On this point he is in disagreement with Bermard Gert and Virginia Held.) A person who is threatened unsuccessfully is not coerced, he argues. Note too, that it is certainly true that we say “He tried to coerce me into doing X, but I refused.” He only tried; he did not succeed. Yet, in the case of liberty, I would suggest, we are a little more tender. If I feel it more difficult to live according to my preferred life style because of the ill-concealed disapproval of my neighbors, even though I do not allow myself to be influenced by them I might consider moving to someplace where I would feel more free to do as I please. I might not say I was coerced, and yet I might contend that my freedom was being infringed upon. What that example brings out is not only that freedom is more a matter of degree than is coercion but also that it has its subjective side. Some might say that a man is as free as he feels; and conversely, that he is not free if he does not feel free. Several years ago, Pitirim Sorokin sought to make this point (and at least one other) by means of a simple formula. Freedom, he asserted, can be reduced to this formula:

where M stands for the sum of the means available (including lack of restraint) and W stands for wants or desires. His primary point was that one could increase one’s freedom as well by limiting his desires as by increasing his opportunities to satisfy his desires. Many might object that, carried to its logical conclusion, the end result of the former process would be death, the very negation of liberty. Yet we do seem to accept the idea that a multiplicity of wants, out of all proportion to the possibility of fulfilling them, is frustrting and that frequently the frustration can be better removed by eliminating the wants than by trying to satisfy them. We might thus think of limiting wants as a way of increasing freedom, since freedom is so closely linked with frustration. Coercion does not seem to enter this picture at all. Yet perhaps this very connection is misleading us here. Gert would protest (and so would many others) that Sorokin’s formula is too inclusive-–that the variable of “means” should be limited to the absence of restraints. This point introduces the well-worn argument as to whether “freedom” should...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Half title

- Title

- Copy

- Preface

- Contents

- Contributors

- 1 Coercion: an Overview

- 2 A Concept of Coercion

- 3 Coercion and Freedom

- 4 Coercion and Coercive Offers

- 5 Coercion, Space, and The Modes of Human Domination

- 6 Spontaneity, Justice, and Coercion: On Nicomachean Ethics, Books III and V

- 7 Coercion and Social Change

- 8 Is Coercion “Ethically Neutral”?

- 9 The Need for Coercion

- 10 Noncoercive Society: Some Doubts, Leninist and Contemporary

- 11 Trust As an Alternative to Coercion

- 12 Political Political Coercion and Obligation

- 13 Coercion and International Politics: A Theoretical Analysis

- 14 Bargaining and Bargaining Tactics

- 15 Coercion in Politics and Strategy

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Coercion by J. Roland Pennock,John W Chapman in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.