eBook - ePub

Picture Books for the Literacy Hour

Activities for Primary Teachers

- 135 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

First Published in 2000. Over the last 30 years, growth in the popularity and provision of books for children has been remarkable. The quality and inventiveness of children's authors and illustrators have led some to think of the picture book as a new art form. This book is a celebration of some of this work and it concentrates on the potential that picture books have for the teaching and learning of literacy. The aim of this book is to encourage colleagues to take a closer look at some of their favourite picture books and to see how they can be used as a starting point for enjoyable and challenging literacy work in primary classrooms. Believing that teachers do not need to rely on schemes to structure their English curriculum and with this in mind this book includes 24 popular titles that have been identified in terms of their potential for delivering exciting text-, sentence- and word-level work. Written to be used as a resource, and anticipate that many readers will be most interested the commentaries on the picture books (contained in Chapters 3- 7) and the accompanying photocopiable activity sheets.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Picture Books for the Literacy Hour by Guy Merchant,Huw Thomas in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Education & Education General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Picture books in the primary classroom

‘While illustrations are not always necessary or desirable in children’s novels, they are an essential part of the picture book … the more rewarding examples of the genre show a complete integration of text and illustration, the book shaped and designed as a whole, produced by a combination of finely balanced verbal and visual qualities.

(Whalley and Chester 1988, p. 216)

This chapter looks at the specific qualities of the picture book and begins with an appreciation of the genre as a distinct category of children’s literature, showing how children bring print and visual awareness to their reading of such texts. We then address a number of questions related to the use of picture books. First we look at the legacy of the ‘real books’ debate as a way of identifying the importance of including picture books in the range of resource material in classrooms. Then we explore how picture books manage to cater for the varied interests of children and adults. This leads to a discussion of how we are drawn into such texts and become active readers, learning with and learning from picture books. We conclude with a look at book formats, the importance of sharing and negotiating meaning and a discussion of the role of the big book in the classroom setting.

Image and print

In their lives at home and in educational settings, children will be introduced to print in a variety of forms from an early age. They will also be growing up in an environment that is rich in visual images. As children learn to take meaning from text they will become increasingly sensitive to how print and other visual information can interact. On television screens, on advertising hoardings, in supermarkets and on public transport, image and print are characteristically seen together. Teachers who make use of these environmental texts are able to promote children’s learning by building on their everyday experiences.

However, despite a healthy and growing interest in different kinds of literacy practices, book-based literacy remains a central part of curricular provision. Picture books provide a powerful introduction to the world of reading by combining children’s sensitivity to the visual image with their growing knowledge of the printed word (Graham 1990). In many primary classrooms children’s enthusiasm for the work of Jill Murphy or Anthony Browne has as much to do with an appreciation of their visual style as with the fictions they create. In fact it could be argued that the real fascination lies in the ways in which print and image interact – how they tell alternative stories or provide additional information.

Probably the picture book is best described as an art-form through which authors and illustrators communicate what concerns them and how they reflect on the experience of childhood. Producing a picture book is primarily a creative process; these texts provide a rich introduction to fictional characters in imagined settings and show children the possibilities of story and visual image as well as the enjoyment that can be derived from reading.

It is perhaps difficult to give a precise definition of the picture book. A wealth of well-illustrated children’s literature is currently available, not all of which is easy to classify. Some titles, particularly those longer stories written for the older primary age range, communicate mostly through print, visual images being employed as accompanying illustration. Others inhabit a sort of border land. Jan Ormerod’s illustrations undoubtedly add another dimension to The Snow Maze (by Jan Mark) and yet the book hardly classes as a picture book. Recent years have seen the emergence of lavishly illustrated information books for children – books in which the visual image has a central part to play. But, in the end, it seems to us that the defining feature of the picture book is the story that it tells and the ways in which it tells it. These books are narratives that are characterised by the dynamic relationship between print and visual image.

Are picture books real?

Several years ago the media contributed to a rather unsettling moral panic over the teaching of reading. We were told that teachers, in large numbers, had abandoned the ‘tried and tested’ structured approaches to teaching reading and were jumping onto the bandwagon of using ‘real books’. This was, in fact, far from the truth but for one important aspect: teachers had begun to realise that children could learn as much, if not more, from books not primarily designed to teach reading – the so-called ‘real books’. In many cases the rather ambiguous term ‘real books’ became synonymous with picture books.

Learning from picture books and learning to read with picture books remain important considerations in our provision of a range of resources in the primary classroom. As teachers become more familiar with planning to the National Literacy Strategy objectives, the opportunities for using good quality picture books are becoming apparent. Texts designed to teach the objectives are unlikely to have the same depth, or range of possibilities. As a recent contributor to The Primary English Magazine observes, ‘The texts chosen need to help the teacher to deliver the objectives; but much more importantly they need to inspire reading’ (Lambirth 1998, p. 29).

Who are they for?

It is sometimes argued that picture books are really written for adults – parents and teachers – rather than children, and certainly it seems that the best picture books do appeal to all ages. The important message here is to understand why they can be enjoyed by different age groups and how this can help the reading process.

… secretly she dropped a poisoned cherry in a cocktail and handed it to Snow White with a smile.

(From Snow White in New York by Fiona French)

Some of the best picture books can be described as being multi-layered, in that they carry a number of layers or levels of meaning. For instance, Allan and Janet Ahlberg’s Peepo! is a simple rhyme about a day in the life of a family, focusing on the children’s point of view. However, on closer inspection, the illustrations reveal that the day’s events are set in a particular social and historical context (another layer of meaning). As we realise that the setting is wartime Britain, and that the father figure is a soldier, another layer of meanings is uncovered, leading us, perhaps, to reflect on disruption and discontinuity in family life. These different layers are embedded in the detail of illustration and text.

Most good picture books can be used effectively with older primary children. A relatively ‘simple’ text can be given a more searching reading in Key Stage 2 or even Key Stage 3. Usually the biggest barrier at this age is created by adults and children who associate picture books with early reading. The sort of narrative complexities we refer to in this discussion of picture books indicate the depth of analysis that is possible. Readers who have come to associate the number of chapters, the size of print or the thickness of the book with reading progress can be re-educated through sensitive teaching. One has only to look closely at Snow White in New York (French) to savour the rich intertextuality as the illustrations evoke a particular setting and the language a particular dialect as this traditional tale is reworked.

So, texts that are rich in meaning can capture the interest of adults and children alike. They can revisit them and learn something new each time they are read. And this means that adults will be motivated to share them with younger readers. Parents, teaching assistants in the classroom and older brothers and sisters will also be interested in what such a book holds for them.

In this way, picture books can be an influential means of building reading partnerships with parents. Rather than simply encouraging reading practice at home they can provide a context for exploring meanings at adult level as well. So, for example, the fascinating accounts of Friedberg and Segal (1997) illustrate how Mary Hoffman’s Amazing Grace provided the context for African-American parents to discuss racism, role models, their own aspirations and their hopes for the younger generation. This is only possible because of the multi-layered nature of the picture book.

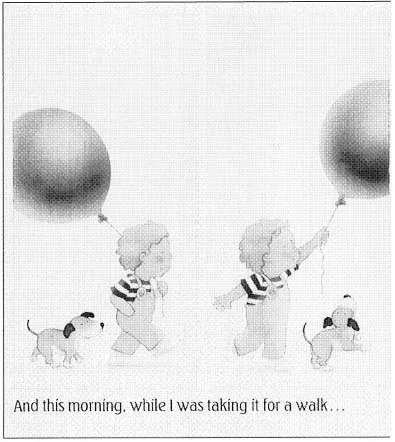

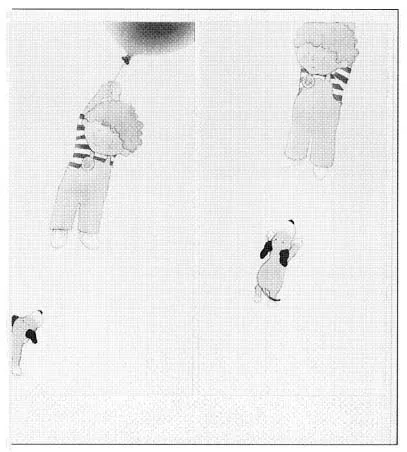

Reproduced from THE BLUE BALLOON, © Mick Inkpen, by permission of Hodder and Stoughton Limited

Do they hold our attention?

For children and adults, one of the attractions of contemporary picture books is the quality of presentation. Although colourful illustration and a clear typeface are not the only criteria for selecting books, technical advances in publishing and printing have undoubtedly provided wider choices for writers and illustrators, the best of whom know how to draw appropriately from the resources available to them.

A growing number of books incorporate sophisticated ‘book technology’ such as moving parts, see-through pages, pop-ups, lift-the-flaps and even electronic sounds and lights. Here, it is important to distinguish between gimmicks and features which seem to add to the meaning of the text. Books that illustrate this dimension include Rainbow Fish, in which reflective foil is used to add another dimension to the fish that is described, and The Blue Balloon, in which pages unfold allowing for illustration and print that extends the meaning of the text.

Some of the best picture books use humour, rhyme or dialogue to draw the reader in in a way that encourages us to think about and reflect upon our own experiences. As we have seen, the subtleties of meaning are not always apparent until we re-read the text or look more closely at the visual images that accompany it. In successive readings we are likely to develop our response to the text and exchange our insights with children.

Authors also make careful use of language to invite us into their stories. This may vary from the imaginative and evocative use of language (for instance Sheldon and Blythe’s The Whale’s Song) to the figurative language of Tigerella (Wright) and the speech patterns of Captain Abdul’s Pirate School (McNaughton).

Often what holds our attention in a good picture book may not be the length of the story or the complexity of the plot, but the enjoyment we derive from the shades of meaning. In fact, the length of most picture books is an advantage here, because they are not too time-consuming to reread.

What can they teach us?

It would be difficult to list all that we can learn from picture books because any list would be as varied as the books we used. Like all good stories, picture books are part of the process of reflecting on life and those who live it, helping us to understand and celebrate the diversity of human experience. However, there do seem to be some common areas in which these books have a key role to play.

Firstly, they introduce us to narrative in picture and written text. By building on children’s existing experience of story, picture books can teach us how stories work. So, for instance, Allan and Janet Ahlberg’s It Was a Dark and Stormy Night provides a humorous insight into the relationship between author, narrator and character as the main character begins to hijack the story. And such devices as the retelling of traditional stories (for example, Jon Scieszka and Steve Johnson’s The Frog Prince Continued or The Three Little Wolves and the Big Bad Pig by Eugene Trivizas and Helen Oxenbury) show us how we relate one story to another.

Secondly, picture books introduce us to different kinds of texts in interesting ways. The letter form propels the narrative of Simon James’s Dear Greenpeace, whereas Babbette Cole’s Dr Dog contains a subtle interplay between narrative and information writing. Other authors and illustrators draw on conventions from different traditions, such as the children’s comic (for example, Colin McNaughton) or the use of visual symbolism in the work of Anthony Browne.

Thirdly, picture books can teach us about ourselves and about others in our culturally diverse society. The visual dimension of the picture book can be a particularly powerful way to present positive images of minority groups (see Merchant 1992). So books like Handa’s Surprise (Eileen Browne) and Masai and I (Virginia Kroll) have a particularly important role to play, not simply because they offer positive images, but also because they are carefully constructed picture books. The picture book can also introduce us to the complexities of contemporary life. For the older reader, a book like Always Adam (Sheldon Oberman and Ted Lewin) offers us insights into the dynamics of ethnic and religious identity through the story of migration and changing traditions. Not only does it develop a sense of empathy, it also leaves us with unanswered questions about continuity and tradition and the development of new identities.

Finally, the visual element of the picture book helps us towards a closer and more critical reading of images. Illustration may also provide support in visualising the story. And so it could be argued that the visual representation of character and setting is helping young readers to see the story: in a sense they are ‘scaffolding’ the imagination.

Reading a picture book, just like reading any other work of fiction, is sooner or later to do with responding to the whole text and bringing meaning to it. It is about gaining information and enjoyment; about raising questions as well as answering them. Good picture books, like all good books, teach us to think: ‘they are machines that provoke further thought’ (Eco 1989).

Is size important?

Picture books are now available in a variety of formats. Publishers have produced small versions of popular titles – as small as a pocket diary or notebook – as well as the standard-sized versions. It is interesting for children to compare different versions and different imprints of the same text. Some titles are also available as ‘big books’ for use as shared texts, perhaps as part of a Literacy Hour or a more informal book-sharing session. As teachers we need to understand when using a big book is appropriate and when it is not.

We would want to argue that the big book has a particular role to play in classroom work. The idea of using a large text has a tradition that predates the National Literacy Strategy. Holdaway’s (1979) descriptions of teachers and children sharing enlarged texts show how this sort of interaction mirrors the sort of learning that happens in more informal contexts, such as when a parent shares a book with a child at home. The advantage of the big book is simply that print and illustration can be seen by all children in the class at the same time. There is no magic – it’s sometimes just easier to share a book in this way. So using big books helps to establish a community of readers in the class – a community that can discuss and reflect upon a shared experience.

Big books also allow the teacher to model specific reading behaviours and to draw attention to those aspects of print and image that are important to the story. So, for instance, we may want to explore why the phrase ‘some things change and some things don’t’ is repeated in Always Adam (Oberman and Lewin), and what effect this has; or why Martin Waddell ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Notes on the contributors

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Picture books in the primary classroom

- Chapter 2 Making opportunities for reading picture books

- Chapter 3 Looking at how stories work

- Chapter 4 Entering imaginary worlds

- Chapter 5 Learning about ourselves and others

- Chapter 6 Exploring feelings

- Chapter 7 Thinking about issues

- Chapter 8 Building up resources

- List of children’s books

- Useful addresses

- Websites

- References